Tischler’s Take: ‘Lincoln in the Bardo’ at Oak Hill Cemetery

By • July 27, 2017 0 1749

“Lincoln in the Bardo” will confound you, will move you and make you feel drugged at times, will challenge your conceptions of what a novel should be — but also reward you with what it could be.

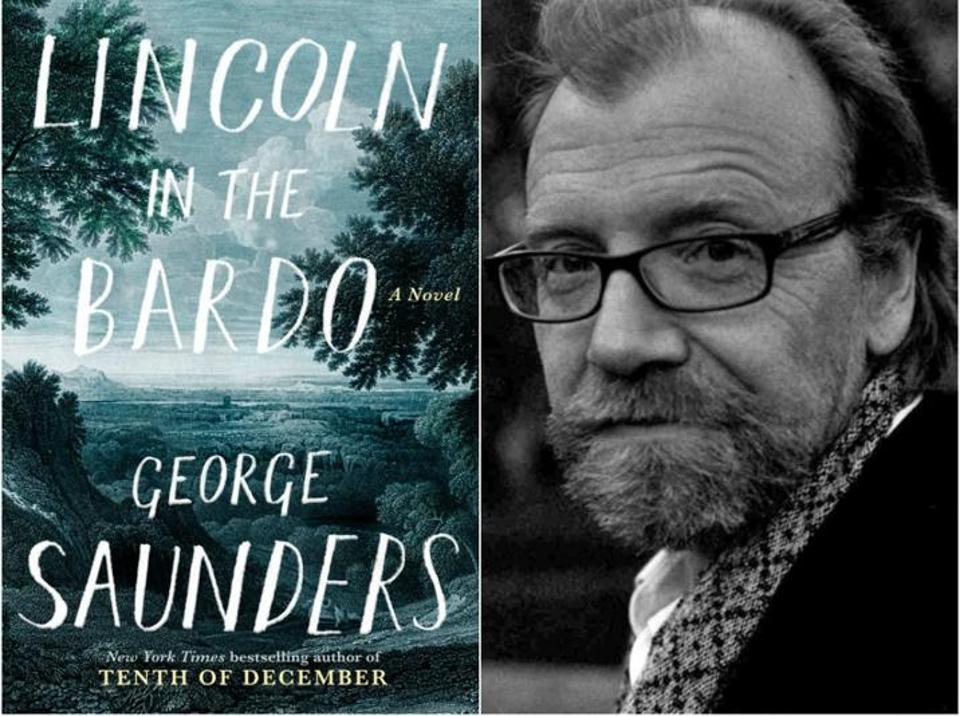

George Saunders, a Pulitzer Prize-winning short story writer, finally published his first novel earlier this year. You can call it a novel—because novels are malleable, multi-dimensional—but it is really something else: a blow to the heart, an eye-opener, just as haunting as many of the apparitions that quasi-people it.

Mostly, although it is about the death of 11-year-old Willie Lincoln in 1862, his temporary interment in Georgetown’s Oak Hill Cemetery, and a grieving, deeply wounded Abraham Lincoln come to hold his son while a vivid series of American types and individuals, denizens of the cemetery who still think themselves alive in their “sick boxes” make themselves heard.

Lincoln’s voice is heard, as is Willie’s, as he arrives here after his death during the course of a lavish receptions thrown reluctantly by the Lincolns, who had been assured that Willie would be fine by a doctor.

But those other voices, those denizens, they are the narrators of this single hell-haunted, explosive, dream-like night. They are in the Bardo, a transitional state described in “The Tibetan Book of the Dead,” a place neither here nor there, but also everywhere.

They include a man whose life was cut short before he could consummate his honeymoon, a man who has killed the object of his affections, a homeless family which sleeps in the fields and thinks mostly of sex and food, a pastor, a woman with three daughters. Some of them have been dead a long time, but still persisted in thinking that they will be restored to their lives and continue living. Periodically, during the course of a stormy night, some are disappeared in a furious flash of light . Their appearance, duly and sharply and hungrily noted, is bizarre.

For Lincoln, it is the second year of the Civil War, and it has devastated him with both the loss now of his son and the greater loss sum of losses suffered by the country and its people, a burden already being keenly felt.

Saunders has fashioned out of this clay not only a novel, but a work that in structure makes description difficult. The book opens with a detailed description of the reception—the people there, the floral arrangements and such. Saunders love lists and so, makes them lyrical, that by accumulation become like an American folk epic.

Alternating between actual fragments from memoirs, biographies, newspaper stories and letters, and the observations and stories of the lives of the host of persons “living” in the cemetery, to invented scenes between Willie and his father, the book becomes a challenge, almost a kind of verbal combat and fight to come to grips with it.

Yet, what a reward to confront a book so original, so inventive, so alluring, funny—yes, funny—and brave. Those beings are a sound to behold.

While a historical novel in the sense that it exists and floats in history, “Lincoln in the Bardo” is a panache-filled, work with its crude-really-crude moments that make you laugh out loud. In fact, as you move through the sometimes terrifying night, you’re tempted to read out loud—something on the order of how one might deal with James Joyce’s “Finnegans Wake.”

It’s contemporaneous, modern in style, but also very much in the epicenter of perhaps what was the most crucial, intense time in national history, a time of sadness and daily mourning everywhere.

“Lincoln in the Bard” has received critical praise from almost every quarter, although its difficulties might keep it from being a best seller. It’s often been compared to Edgar Lee Masters’s “Spoon River Anthology”, the book length poem in which the residents of a small town rise from their graves to try to explain their lives, or Sherwood Anderson’s “Winesburg, Ohio” or the last sections of “Our Town.”

For myself, I often hear Walt Whitman, the poet of the great American everything and everybody and Lincoln and the Civil War.

In every corner of the book lies a story, and everybody gets to tell it, in their own vernacular. So it is with Lincoln and the slaves who occupy another part of the cemetery—they too have not been freed yet.

And Lincoln, whom some have called the saddest president in history, frees himself too, notes his own forever mourning, rises up from his son and rises with tears and determination.

Contemplating the possible failure of democracy, Lincoln thinks, inside himself “…if it went off the rails, so went the whole kit, forever and if someone ever thought to start it up again, well, it would be said (and said truly): The rabble cannot manage itself.”

Well, the rabble could. The rabble would.

He would lead the rabble in the managing.

The thing would be won.