Edvard Munch at the National Gallery

By • October 11, 2017 0 1402

Edvard Munch (1863–1944) is in a unique category of artists. Like Sandro Botticelli, Walt Whitman, Harper Lee and George Lucas, Munch is a rather permanent fixture of Western culture, whose name is synonymous with a single work of art.

There are fewer artists of this fate than at first it may seem. This statement might be made about many of history’s greatest artists; Leonardo da Vinci is synonymous with the “Mona Lisa,” van Gogh with “Starry Night,” Michelangelo with the Sistine Chapel. But there is at least a general awareness among the art-going public that these artists existed beyond their seminal masterworks. Most people have heard, for instance, that da Vinci designed concepts for helicopters, that van Gogh cut off his own ear and so on.

When it comes to Munch, I don’t imagine that most people have even a vague awareness of the artist beyond “The Scream.”

Now, this is hardly a tragedy. The boundless majority of all artists in history would happily murder their fathers for the chance to have any of their work leave such an indelible mark. But in the case of Munch, there is something quietly unfortunate about this limited legacy, since his larger body of work is among the strangest, most haunting, spiritually penetrating and existentially beautiful of the turn of the 20th century.

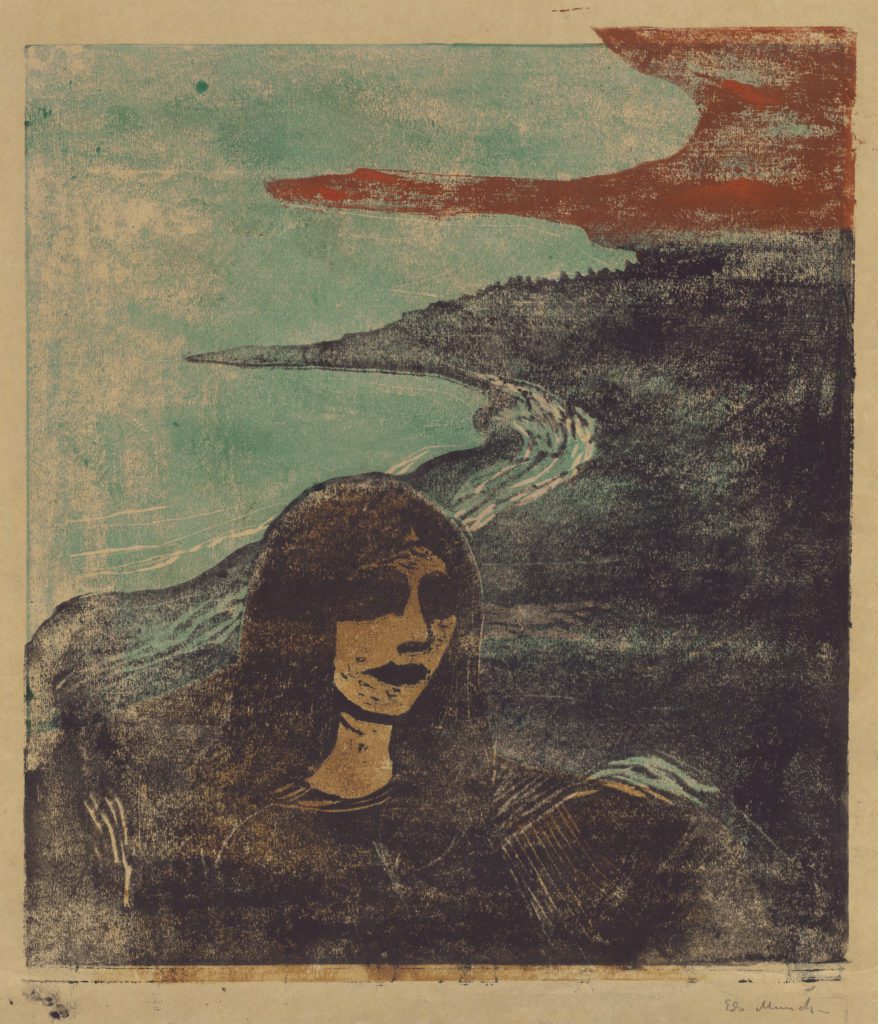

Most fascinating are his prints, in which he experimented compulsively and with nimble, unfussy impulse, offering viewers a rare direct connection to the clockwork of an artist’s mind.

Thanks to a significant donation of works by the Epstein Family Collection, the National Gallery of Art has steadily rolled out alternative exhibitions of Munch since 2010, and will

eventually amass the largest and finest collection of Munch’s prints and graphic work outside of his native Norway.

The current exhibition, “Edvard Munch: Color in Context,” on view through Jan. 28, focuses on the influences of 19th-century scientific and spiritual advancements on Munch’s practice. Through a focused, beautifully selected collection of prints, the show explores the meaning in Munch’s use of color. Specifically, it considers how this aspect of his practice relates to color’s meaning in a theosophical context.

Theosophy was a popular philosophy in the late 19th century, a group of mystical and occultist theories that delved into what were believed to be unexplainable mysteries: life and death, the nature of the divine, the origin and purpose of the universe.

It seems to me that this era’s fixation on spirituality and metaphysical phenomena — clairvoyance, alchemy, mesmerism (hypnosis) — resulted from a deluge of massive scientific discoveries, like x-rays and radio waves, that were ahead of the public’s understanding of them.

For example, the discovery of x-rays in 1895 illuminated the limits of the human senses. Developments like this moved progressive artists and thinkers away from basic interpretations of nature.

Imagine a world experiencing for the first time a machine that can photograph human bones beneath the skin or capture the audio static of space dust. Without a cultural awareness of these innovations, let alone an understanding of them, it is not hard to see how they could foster mystical, pseudo-philosophical interpretations akin to religious grandeur. And so, I believe, theosophy was born: a new set of whimsical theories by which to explain the cosmos.

This is all well and good, and it certainly establishes a riveting context for displaying Munch’s exquisite prints. But it does not explain what makes Munch’s work so compelling and so addicting.

Through his woodblock prints, Munch experimented simultaneously with tone and technique, often changing coloration within a print series. He worked in shape and color interchangeably, overpainting and touching up his prints by hand. The woodgrain often guided his blade, influencing their patterns, shapes and direction. Prior to the early 20th century, there are very few existing records of this type of wild, breakneck artistic tinkering. Munch might well be among the earliest artists whose studio experimentation is so well-preserved.

That he worked in woodblock is all the better; I have always thought woodblock the most direct connection one can get to an artist. There is no opportunity for erasure in a woodblock, no editing or covering up or augmentation. Paintings can be reworked, sculptures can be retooled, drawings can be smudged, erased and manipulated in a thousand ways. But the moment a blade cuts into a woodblock, it creates a permanent record.

Unlike the bold coloration of his paintings, Munch’s prints were games of raw space. “The Kiss in the Fields” is a woodcut printed in red-brown ink and touched up with watercolor, showing a couple entwined amid a vast and liquid landscape. To all intents and purposes, it is entirely abstract, like a slow receding of figures, shapes and dimension back into the ether of the world.

His “Melancholy” series of figures on the beach obliterates the experiential boundaries of figure and landscape; bodies become planes of shoreline and grooves in the sand an extension of the subject’s very mood.

Munch created a timeless masterpiece in “The Scream,” but his greater body of work echoes deeply beyond this single canvas. More than an artist worth knowing, he is the kind of artist worth immersing oneself in, and returning to again and again.