Encounters with ‘Hamlet’

By • January 24, 2018 0 943

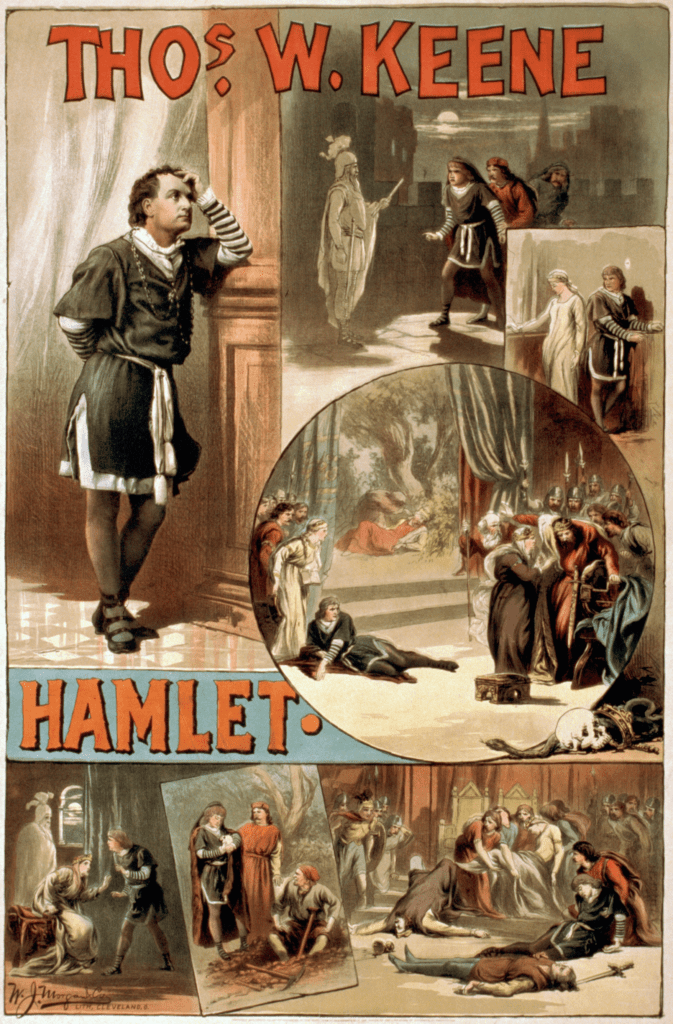

Once encountered — preferably onstage, acting a part, however small, but also as a high school English assignment — William Shakespeare and his most familiar creation, “Hamlet,” about that melancholy Danish prince, never leave you.

And here they are again, threefold, in Washington, D.C.

Right now, Michael Urie is playing Hamlet in a Shakespeare Theatre Company production directed by longtime Artistic Director Michael Kahn. The production, at Sidney Harman Hall, has now been extended through March 4. Kahn has directed what is arguably the Bard’s greatest play twice before in recent years. Since he has announced that he is retiring at the end of the 2018-19 season, it’s quite possible that this is his last go-around with world theater’s most redoubtable, enigmatic, unforgettable character.

Overlapping with STC’s production, from Feb. 6 to 18, the National Theatre will host the national touring company of the Tony Award-nominated musical (yes, musical) “Something’s Rotten!”

But, wait, there’s more. The Royal Shakespeare Company is bringing its much praised, edgy production of “Hamlet” to the Kennedy Center this spring, from May 2 to 6.

In the words of Osric, judging one of Laertes’s sword jabs at Hamlet in the climactic dueling scene, “Hamlet” is still “a very palpable hit.”

For theater fans, for people interested in what makes people tick, for whom all the world’s a stage, there are, in terms of “Hamlet,” all sorts of moments that are like a first contact, a first kiss and, finally and forever, a sighing surrender.

I touched base with “Hamlet” for the first time through a comic book, one of the old-timey Classics Illustrated comics that included some of Shakespeare’s works among its hundreds of comics (you could call them graphic novels, but they did not) from the 1940s and later. It included a speech, the one that begins “To be or not to be,” filling up the whole page, with a tiny Hamlet at the bottom contemplating murder.

I can’t exactly remember where I first saw a stage production, although the old Hallmark Hall of Fame classic, often live, dramas would have included “Hamlet.” It was Laurence Olivier’s spooky black-and-white film version which he directed, and which won an Oscar for best picture in 1948, where I first encountered a living prince, and a fairly crazed and kinetic one at that, blondish-white-haired and intense, battling Laertes, pirates, the clueless Rosencrantz and Guildenstern and poor Jean Simmons as Ophelia.

Hamlet thrived on the cinema screen and actors who portrayed him did too. It’s hard to forget Kenneth Branagh’s full-length version, so richly peopled and performed.

But the real legends exist onstage, therefore in the mind: Olivier and Gielgud were apparently dueling princes in the 1930s of very different styles. Most recently onstage, there was Benedict Cumberbatch. The list also includes Nicol Williamson, Derek Jacoby and, yes, indeed, Mel Gibson, who was surprisingly good.

The encounters were not always pleasant. Bad ideas are still bad ideas, as when an aging Judith Anderson took on the part in a production I saw in San Francisco in the 1970s.

But a live Hamlet is a live Hamlet — in whatever format, setting and costuming. What matters is not so much what we see in him, as what others do. He changes with the times, quite literally, and there’s been quite a lot of critical writing that, if it doesn’t entirely explain Hamlet, brings him directly into the times we live.

With Hamlet, there’s, as Gilda Radner once said “always something.” Theater folks get special delight out of Hamlet’s admonitions to the players on how to act. Shakespeare was after all a theater person: he counted the coins, he bought the costumes, he acted and cast and above all wrote the plays.

Others, in their time, cut right through to the darkness, that almost subterranean world of Elsinore, where people whisper lest they be heard, where people hide behind the curtains, where murder most foul is committed — on a certainty with poison, by accident with Polonius.

I can think of no other view of “Hamlet” as a kind of living, livid ghost than in “Shakespeare, Our Contemporary” by Jan Kott, the Polish critic who saw Elsinore as an authoritarian state where tyranny and secrets were stock in trade, a theme that echoes vividly in our digital age.

There are and have been thousands upon thousands of “Hamlets.” In the 1980s, I saw a production by British film director Lindsay Anderson at the Folger Theatre. At the start, there was a stageful of dead bodies. Horatio is cradling a supine and bleeding Hamlet, slain at the play’s climax. After speaking the line, “Good-night sweet prince,” he turns to the audience and says: “You are probably wondering what happened here” or words to that effect (since these are not the Bard’s words).

“Well, therein lies a story,” he concludes, and so the play begins. It is a story, as well as a play, as well as a dream.

Very few productions of a full length “Hamlet” are ever staged, since they tend to run around four hours or more.

In 1976, I had the opportunity to perform — yes, perform — in the shortest version, “The Fifteen Minute Hamlet” by Tom Stoppard. I did it at the suggestion of a director friend of mine, who thought it was a good idea for a critic to come at things from the inside, much as Hamlet himself tended to do. In tights, I played the part of a second Osric, a very small part to begin with. I alternated from fear to exhilaration.

I had one line: “A hit, a very palpable hit.”