Reviewed by Kitty Kelley

Nothing sells like books on sex, diets and the Kennedys. If you wrote “How JFK made love to Marilyn Monroe on 150 calories a day,” you’d have an instant success. Just ask J. Randy Taraborrelli, who’s been mining two of those three veins for the last 20 years.

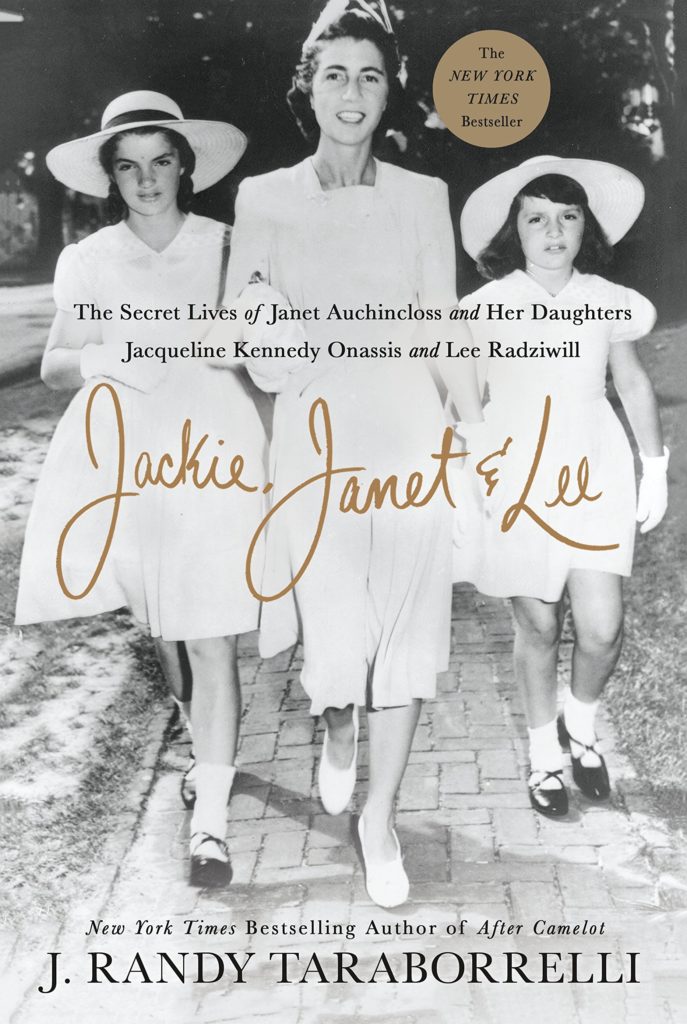

In 2000, he wrote “Jackie, Ethel and Joan: The Women of Camelot,” which became a two-part series on CBS-TV in 2001. He wrote “After Camelot” in 2012 and, six years later, he now presents “Jackie, Janet and Lee: The Secrets of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, Janet Auchincloss and Lee Radziwill.”

Spoiler alert: He adores Jackie and abhors Lee. The big reveal, according to his publisher’s press release, is that (supposedly) their mother, Janet Auchincloss, performed do-it-yourself artificial insemination in order to get pregnant twice after she divorced their father and married her second husband, Hugh D. Auchincloss. Janet was 37; Hugh was 58, and had had three children by two previous wives. Yet we’re asked to believe that Mr. Auchincloss was incapable of impregnating Mrs. Auchincloss in 1945 and again in 1947.

And — hang on here — we’re even told why: “Even though Hugh was not able to sustain an erection, he was able to produce sperm … [and Janet] used a kitchen utensil along the lines of a turkey baster — though it would be incorrect to say that this was the specific instrument she used; no one can quite remember ….”

With eyes popping, I turned to the chapter notes for documentation on this “never before revealed secret.” Under source notes for “Janet’s Unconventional Pregnancy,” Taraborrelli writes: “Because of the sensitive nature of this chapter, my interviewed sources asked to remain anonymous.” Huh?

With Mr. and Mrs. Auchincloss deceased for many years, you might wonder what possible “sources” could’ve been interviewed about their intimacies in the bedroom. No documentation is provided, other than the author’s note that he recycles sources from his previous books. Then, like a bird feathering its nest, he snatches twigs from yellowed newspapers and wisps from tattered tabloids while plucking from the vast trove of other published lore, which Jill Abramson in the New York Times estimated to be 40,000 Kennedy books.

In this book, some readers might be troubled by the lack of attribution for “she felt,” “he thought,” “said an intimate,” “revealed an associate,” “confided an employee” and “reported someone with knowledge of the situation.”

Others might be puzzled by the personal quotes Taraborrelli does attribute, particularly a story about Janet giving her daughter, Lee, a check for $650,000, saying: “For any time I ever let you down, I’m very sorry. Maybe this small gift will make your life a little easier. I love you, Lee.” Taraborrelli follows with: “We don’t know Lee’s reaction; she’s never discussed it and only she and Janet were in the room at the time the gift was presented.” So how is it that Taraborrelli, who was not in the room, can gives us Janet’s exact words?

Perhaps the quotes come secondhand from Tarborrelli’s main source for this book: James “Jamie” Auchincloss, the 71-year-old son of the aforementioned parents, and the half-brother of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis and Lee Radziwill. “[H]e never refers to Jackie and Lee as ‘halfs,’” writes Taraborrelli. While Jamie may refer to Jackie and Lee as his sisters, neither claimed him as family.

Full disclosure here: I met Jamie Auchincloss in 1975 when I was writing a biography of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis. That book (“Jackie Oh!”) received attention because my interview with former Sen. George Smathers from Florida was the first time a Kennedy intimate had gone on the record to discuss the president’s extramarital affairs.

Smathers’s details were so graphic that at one point I remember saying, “Senator … um … with all due respect … may I ask … how you could possibly know that … unless you were actually in the room with him?” Smathers chuckled. “Well, of course I was in the room with him. Jack liked making love with others around …. He was just like a rooster getting on top of a hen.”

During our three-hour interview, Sen. Smathers confirmed that Jacqueline Kennedy had received electroshock therapy for depression after losing her first child, Arabella, in 1956. Published 20 years later, my book also revealed for the first time the prefrontal lobotomy performed on the Kennedys’ oldest daughter, Rosemary, who was severely diminished by the surgery, and as a result spent the rest of her life in the care of the nuns at St. Coletta’s in Wisconsin.

While Jamie Auchincloss was not the source of the more controversial material in my book, he did speak openly about his famous relatives and, unfortunately, he paid a price. Appearing on Charlie Rose’s local talk show a few years later, he said that Jackie stopped speaking to him after my book was published, much as she had with others whom she felt had shared too much personal information about the late president, including Ben Bradlee, who wrote “Conversations with Kennedy,” and Paul “Red” Fay, a Navy buddy of JFK, who wrote “The Pleasure of His Company.” When Fay sent his royalty check to the Kennedy Library, Jackie sent it back.

A few years ago, Jamie Auchincloss moved from Washington, D.C., to Oregon where his life plummeted from the height of being the six-year-old page boy who carried the wedding train of his sister’s gown when she married John F. Kennedy to the scandal of being jailed at the age of 67 for possession of child pornography. In 2009, he pleaded guilty to distributing what prosecutors called lewd and lascivious images, and was charged with two felony counts for encouraging child sexual abuse.

He spent Christmas 2010 in jail. Failing to cooperate with his court-ordered sex offender treatment program, he was sentenced to eight months in jail, serving just over half the time behind bars and the rest in home detention. He was put on probation for three years, ordered to stay away from children for the rest of his life and to register as a sex offender.

Taraborrelli writes that “this unfortunate turn in Jamie’s life in no way impacts his standing in history or his memories of growing up with his parents … and siblings …. Or his brothers-in-law, Jack, Bobby and Ted Kennedy. The times I spent with Jamie were memorable; I appreciate him so much. He also provided many photographs for this book.”

If you’re a reader who requires corroborated information and credible sourcing in your nonfiction, this book will give you pause. Then again, if your requirements are less stringent, you might enjoy the photographs.

Among Kitty Kelley’s many books is “Capturing Camelot: Stanley Tretick’s Iconic Images of the Kennedys.” In two 1988 cover stories for People magazine, Kelley broke the story of Judith Exner’s confession that, in addition to being JFK’s lover, she was also his conduit to the Mafia, carrying his messages to Chicago mob boss Sam Giancana.