Georg Baselitz at the Hirshhorn

By • July 25, 2018 0 2081

In the wake of World War II, Germany was in ruins. What remained was a vast landscape of bombed-out cities and scorched countryside, and a generation of lost families, ashamed in their despair, silently mourning the death of millions of their people while trying to keep from starving.

For the children born into this nightmare, it must have left profound and indelible marks.

Over the next 15 years, tensions flared between democratic Western Europe and the communist Eastern Bloc. Germany’s capital city of Berlin became the arena for a high- stakes standoff between the two global forces that had delivered its defeat. The Berlin Wall went up in 1961, inking the scars of a country torn apart and delineating a global ideological crisis that would continue into the end of the century.

But artistic traditions found their way. The children of the war were now young adults, and their view from the ravaged epicenter of modern Western conflict produced startling results that remain troubling and transfixing today.

The painter Georg Baselitz, whose work came to maturity in 1960s Berlin, is one of the leading figures to emerge from postwar Germany. His lifework fights to reaffirm the triumph of individual artistic freedom over mass ideologies and dogmas.

Bringing paintings and sculptures together with works on paper and archival materials,“Baselitz: Six Decades,” on view at the Hirshhorn Museum through Sept. 16, traces Baselitz’s career from his early work excavating the postwar German condition to his somber, meditative self-portraits of the past few years.

Saying this might be taboo, but war is good for art. Baselitz was well set up to produce works of sociocultural import. Faced with the arduous task of confronting their traumatic past, artists in postwar Germany underwent something like a dystopian Renaissance, creating some of the most distinctive and experimental art of the 20th century.

As Baselitz himself noted in a 2017 interview: “I’ve no idea how I could ever have become a painter in California.”

Countless artistic movements were born out of Cold War Germany, many of them hugely influential: Fluxus, social sculpture, Neo-Expressionism, the New Leipzig School, the Dusseldorf School, Capitalist Realism.

German painters like Baselitz, born in wartime, revisited the traditions of German Expressionism, an atmospheric, deeply personal, often whimsically grotesque style practiced in the World War I era by artists like George Grosz and Otto Dix. Rooted in classical traditions of observational painting, its model functioned as an aesthetic and philosophical alternative to the conceptual and minimalist art that was dominating the West by the 1970s.

One can imagine that Baselitz, who was kicked out of East Berlin’s academy of fine arts in1957 for not complying with its state-sanctioned art form of “social realism,” might have thirsted for a more explicit and corporeal purpose to his work than minimalist abstraction could offer.

His work from the early ’60s is visceral and grisly: bodies that are at once bloated and emaciated, bruise-tender and green with rot, all organs, erections, shorn hair and scabs. Anatomy is distorted and rearranged, hands and feet are swollen. The surrounding spaces are dark, bare, but confined, with low horizon lines that evoke claustrophobia.

The paintings are aggressively priapic, but their subjects display no awareness of sexual sensation. They emit only a dull ache, an unremitting low-level shame and suffering.

There are hints of Francis Bacon, Lucien Freud and Frank Auerbach in these paintings, but without the thin, vague membrane of attractiveness that those artists could never quite divest.

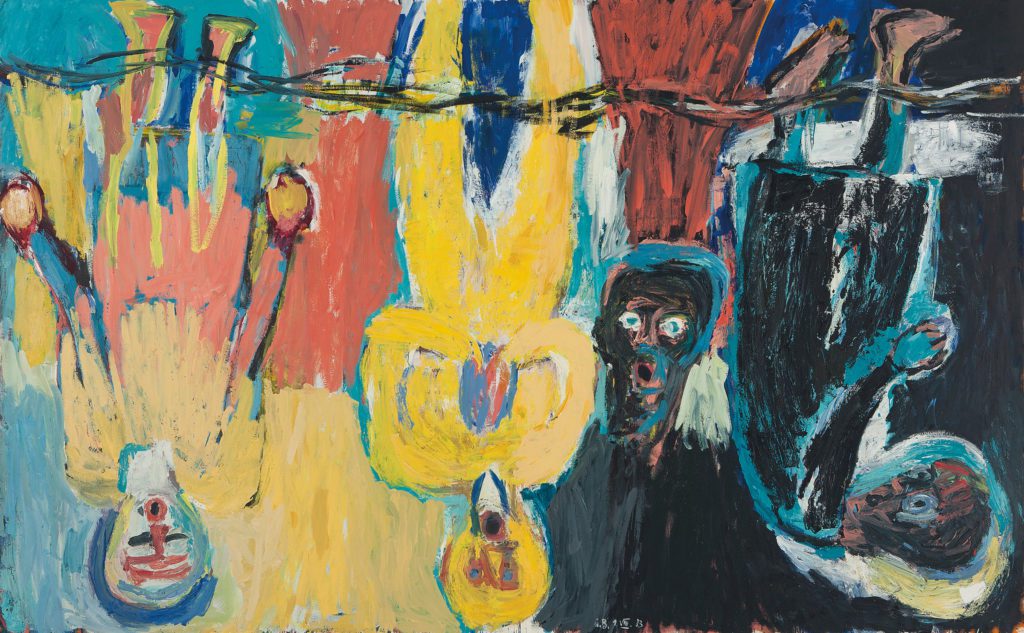

“Orangenesser IX (Orange Eater IX),” 1981. © Georg Baselitz 2018. Skarstedt, New York. Photo by Friedrich Rosenstiel.

Among Baselitz and his German contemporaries like Markus Lüpertz and Anselm Keifer, the aesthetic persistence of the grotesque runs deep. Judging from this exhibition, Baselitz has hacked, scratched, slashed, smeared and raked his canvases (as well as wood sculptures and woodblock prints) for the past 60 years.

This isn’t to say his work his static. The iterations and effects he produces are endless and often ineffable. He has moved through contemplations of metaphorical and material landscapes, intimate portraits of friends and family, industrial complexes and nudes. He has even inverted his canvases to question perceived relationships of the painting to the“image.”

However, a subtle but remarkable transition seems to have occurred in the 1970s. Working with his canvases flipped upside down, and having spent at least a decade exploring the gruesome physical and psychological nature of his country, Baselitz’s paintings suddenly became remarkably beautiful. His colors unmuddied and lightened, the faces of his subjects softened and their bodies returned to recognizable anatomy. Trees grew leaves, spaces and shapes became expressive with life.

It was as if the rotation of the canvas upended his perspective and something soft and naturalistic took over. Paintings like “Nude – Elke” (a portrait of his wife) and “Finger Painting – Apple Tree” reveal an intimate world of hidden beauty amidst a country ostensibly in turmoil. Remember, this is 1970s Germany at the height of the Cold War. These paintings almost give hope to such bleak conditions, and they certainly offer beauty as a remedy.

By the 1980s, however, the soft oranges and deep frosted blues turned to alarming neons, and the tonal grayscales reverted to silty clay and black. Baselitz had grown accustomed to the new perspective, I suppose, and trauma will always find ways to resurface.