Reviewed by Kitty Kelley

This slim novel by Gaute Heivoll, translated by Nadia Christensen, presents the life of a couple we know only as Papa and Mama. The pair built a home in southern Norway for themselves, their two children and several “boobies,” the term used by the children’s mentally deficient uncle, Josef, to describe the five deranged siblings who come to live with them at the end of World War II.

The siblings — two sisters and three brothers — barely able to function, are taken from an apartment heaped with garbage, mouse-eaten mattresses and piles of human waste after their parents are declared unfit.

They are saved from being institutionalized when Papa and Mama sign a contract to provide for their care in exchange for a small stipend from the state. The children arrive on a cold, snowy evening in February of 1945. Watching them get out of thecar, Uncle Josef says, “So these are the new crazies.”

Telling the family’s story 50 years later, after Papa and Mama have died, is thesurviving son, who knows that working with the mentally disabled was what gave meaning to his parents’ lives — particularly to his father, who had worked for 11 years at a psychiatric hospital.

“That was when I felt alive,” Papa said about the time he spent caring for youngsters who howled like wolves and adults who could not sit up or feed themselves. It was also where he met Mama, a nurse working in the women’s unit. After they married, they dedicated their lives, according to their son, to caring for the mentally incapacitated “in a Christlike spirit of love.”

At that time, Norway was considered a Christian country, even though statistics show that regular church attendance was (and still is) as low as five percent. Although no longer formally designated as Christian, the Viking kingdom is progressive on issues of morality. This novel, translated from the Norwegian, is a powerful testament to humanity — a tribute to those unique individuals who care for the most fragile among us.

That noble grace of charity is rarely found, even among princes of the church, as the novel underscores when a new minister visits Papa and Mama at home. The pastor is shaken by “the madhouse” he sees. So much so that, when he stands at the pulpit the following Sunday, he tells his congregation — which includes Papa and Uncle Josef — about his visit, suggesting that the drooling, incoherent people he met were subhuman-like animals:

The incident made Papa furious … After that he often spoke about [it]. Still indignant, yet lenient, as if the whole thing had been a misunderstanding. Of course, they were human. They were happy children. God wanted them to be happy children.

Stipend or no stipend, how many people of modest means living in a harsh climate with no amenities would open their homes to the deranged and fold them into their family? Answering that question for yourself will draw you into the heart of this story, with its small joys and immense tragedy.

Soon you begin to care about the characters, including the man-child who sits in the yard under an ash tree in the same spot on the same stool staring into space everyday for more than 20 years. “No one took his spot, and no one knew what he hadseen. The shimmering light from imprisoned souls. Or only clouds and sky, wind andnothing.”

At times, I caught my breath in sadness over the mentally impaired in this story, who grow old but never grow up, especially a young girl named Ingrid, one of the five siblings, who cannot speak but listens intently and seems to comprehend on a visceral level.

She howls when she feels psychic pain, like she does when told her older brother and sister are being taken to be sterilized. “We understood that an important event was going to occur, but once the word was mentioned, it wasn’t explained or discussed further.” Neither to the children nor to the reader.

For those unfamiliar with Norway, the places mentioned — Tordenskjoldsgate, Brandsvoll, Naerlandsheimen, etc. — might require a map, but the atmospheric descriptions of majestic glaciers, deep fjords and dense, snow-laden forests suggest a country of wondrous nature that author Heivoll obviously loves. He tells his story with unadorned prose that sometimes shimmers. When Uncle Josef sees snowfalling from the sky, he says, “The angels are dancing until their feathers fly.”

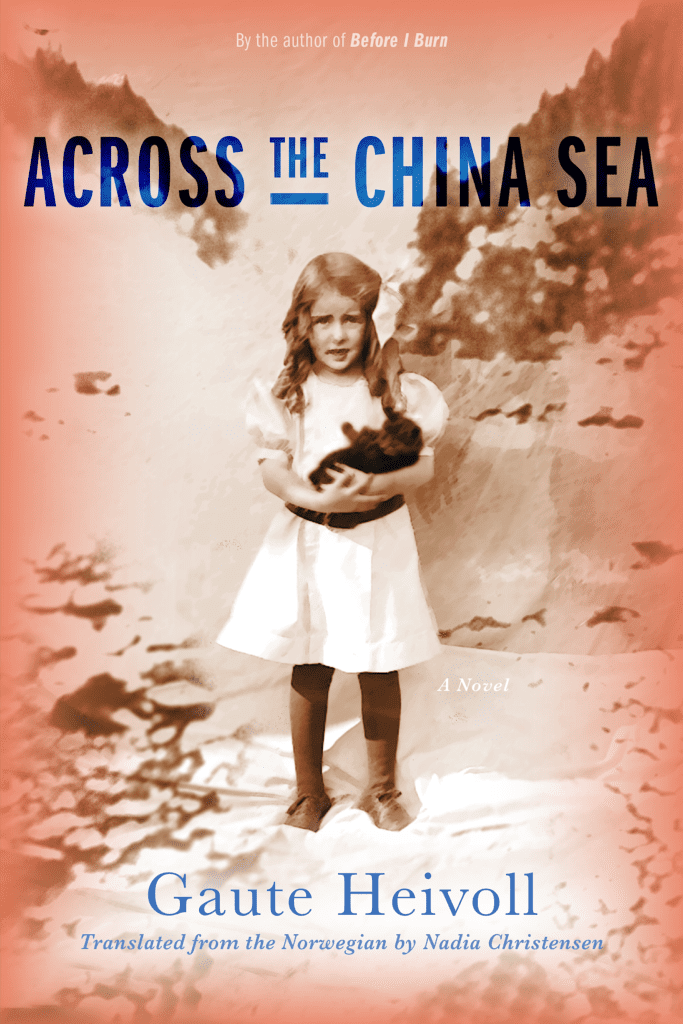

The title of the book comes from a crate filled with oranges that came across theChina Sea and ended up in the attic of Norway’s psychiatric hospital, where Papafinds it and decides to use it as a bed for the children he has with Mama. Perhaps that sturdy crate is a metaphor for the patchwork family that manages to endureone of life’s greatest tragedies and find a patch of blue sky.

When I came to the poignant end of the novel, I thought of William Faulkner’s 1950 Nobel Prize address, in which he spoke of “a life’s work in the agony and sweat ofthe human spirit, not for glory and least of all for profit, but to create out of the materials of the human spirit something that did not exist before.”

Georgetown resident Kitty Kelley has written several number-one New York Times best-sellers, including “The Family: The Real Story Behind the Bush Dynasty.” Her most recent books include “Capturing Camelot: Stanley Tretick’s Iconic Images of the Kennedys” and “Let Freedom Ring: Stanley Tretick’s Iconic Images of the March on Washington.”