Dawoud Bey’s “The Birmingham Project”

By • October 10, 2018 0 819

On Sunday morning, Sept. 15, 1963, members of the Ku Klux Klan planted dynamite with a time delay beneath the steps of the 16th Street Baptist Church, an African American church in the center of Birmingham, Alabama. Just before 10:30 a.m., the bomb went off near the basement, where five young girls were changing into their choir robes. Four of them were killed: 11-year-old Carol Denise McNair and 14-year-olds Carole Robertson, Cynthia Wesley and Addie Mae Collins.

The murder of these four young girls is ingrained now in the conscience of our country —probably not as well as they should be, but well enough for a nation of our evidently limited domestic hindsight. It was a turning point in the civil rights movement, which galvanized a national sympathy for the plight of the African American people. Within 10 months of the bombing, President Lyndon Johnson had signed the Civil Rights Act into effect. (John F. Kennedy, a vocal civil rights advocate, was shot just two months after the bombing, and the effects of his murder on the movement should not be overlooked.)

Fewer people are aware of what happened in the immediate aftermath of the bombing, or of what happened to the fifth young girl caught in the explosion. Dawoud Bey remembers, and it has been burning in his consciousness for over 50 years.

Bey was 10 years old in 1963. As a child in Queens, he recalls “the ground-shifting trauma” of seeing a photograph of Sarah Jean Collins, the survivor.

Sarah, the younger sister of Addie Mae, had glass debris embedded in her face. A photograph captured her in a hospital bed, with a robe pulled up to her chin and a large white cotton ball taped unevenly over each eye. But for the cotton balls and lacerations across her cheeks and forehead, it is the perfect image of a sleeping child, blanket pulled up to her chin, the evening-tea vision shared by every parent who has ever stolen a glance at their child sleeping through a cracked door.

In many ways, Bey’s “The Birmingham Project” is a deep meditation upon that memory, upon what was lost that day in Birmingham, the alternative future that might have reverberated from that moment. It is a powerhouse of a show, with just four photographs and one video throughout two small galleries that together contain multitudes.

A photographer that walks the line between documentary and fine art, Bey has photographed American youth and marginalized communities for 40 years, revealing a sensitivity and complexity rarely ascribed to his subjects.

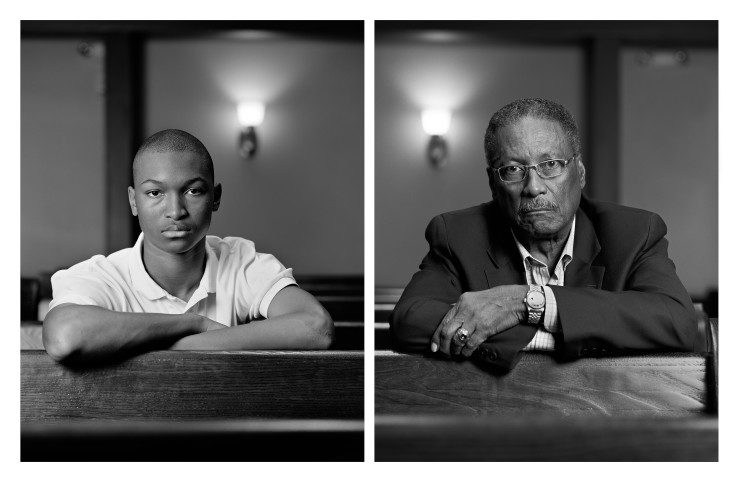

At the National Gallery of Art, “Dawoud Bey: The Birmingham Project” is an excerpt from the series, a tribute to the victims of the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing. Bey visitedBirmingham several times over seven years and solicited sitters from the city’s present-day African American community. After photographing people individually, he paired two portraits, one of a younger black adolescent and a similar looking subject of late middle age. The adolescents were the same age as a victim in 1963, the adults 50 years older, marking the children’s ages had they survived.

As is his usual practice, he invited his subjects to dress and pose freely. Yet through this process he found pairs of subjects that, though separated by half a century, seem to share remarkable spiritual connections.

There are four portrait sets on view in the gallery, two sets of women, two sets of men. The men represent two teenage boys killed the day after the bomb by Klan members and white nationalists (including a police officer) who had gathered publicly to celebrate the church bombing.

Betty Selvage and Faith Speights sit in the same chair in the same place. Selvage, the elder, leans toward the camera, arms folded on an armrest, bold, defiant, in a smart and fashionable blazer. Speights, the younger, assuming a near identical posture, turns this pose into something resembling a school portrait. She is slightly stiff and studious, the way you imagine she has been taught to sit at the dinner table. She is wearing a silk blouse and glasses that lie crooked across her face. It is endearing and kind of adorable, conjuring the empathic admixture of love and pity one feels for an awkward preadolescent from the vantage of maturity. In the context of “The Birmingham Project,” it is devastating.

The portrait titles use the subjects’ real names. They are not actors assuming the roles ofthe bombing victims. Rather, they are prisms through which the lost lives of the past resonate through the geography and community that connect them to this history.

Finally, Bey’s video “9.15.63” is a split-screen projection juxtaposing a recreation of the drive to the 16th Street Baptist Church, shot from the window of a moving car looking up at trees and the roofs of houses from the perspective of a young child. On the left, slow pans move through everyday spaces — some familiar (a beauty parlor, a barbershop), some politically charged (a lunch counter, a schoolroom). They look as they might have that Sunday morning in September 1963. Devoid of people, these views poeticize the innocent, mundane existences ripped apart by violence.

It is 2018, but as Bey shows us through the lens of his camera and with a surprising political restraint for the current moment, the reverberations of that long-ago day in Birmingham are still strongly present among us all.