‘Japan Modern’ Focuses on Prints, Photographs

By • October 24, 2018 0 1094

In 1853, Commodore Matthew Perry steered his squadron of U.S. Navy battleships into Edo (Tokyo) Bay to pressure the Japanese government into opening ports to American mercantile ships. Perry’s arrival set in motion the collapse of the shogunate, a centuries-old institution already weakened by an ailing leader and political indecisiveness.

Over the next century, Japan careened violently into modernity. Within 100 years, atomic bombs had been dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and Japan was struggling to rebuild its urban centers — as well as its very identity — amid a new world order.

It’s hard to imagine how disorienting it must be as a people to watch as your world history dissolves in the face of highly advanced foreign intervention. Despite 700 years of feudal isolation, 19th-century Japan, though still an agrarian nation, was quite culturally and technologically sophisticated. Commodore Perry’s arrival with a fleet of steam-powered warships might be comparable to an ion-fueled alien spacecraft landing on the National Mall today.

Prominent intellectuals of the era called for the Japanese to embrace Western lifestyles and technology, while other voices advocated for them to retain traditional values. Artists, caught between these conflicting positions of imported and local culture, were forced to reconcile them in a fundamental reshuffling of art and life in Japan.

On view through Jan. 24, “Japan Modern,” a pair of exhibitions at the Smithsonian’s Freer and Sackler Galleries, explores the seismic shifts within Japanese art from the 1850s through the 1970s.

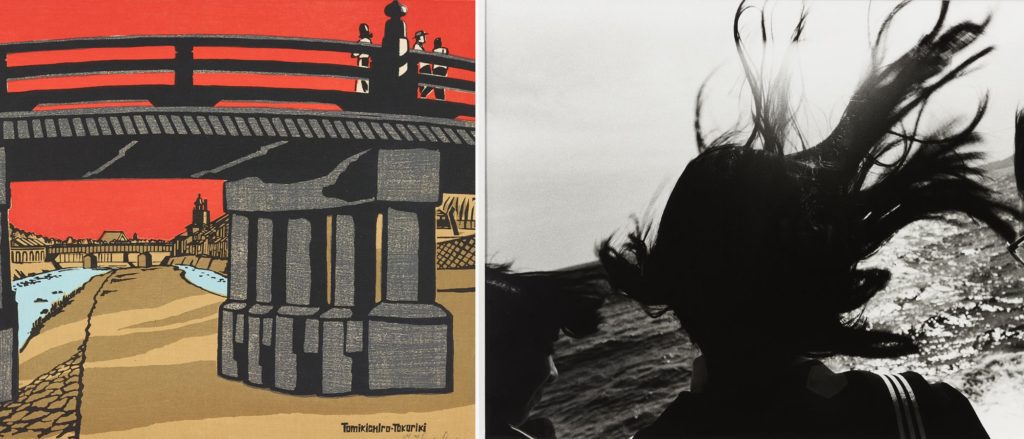

The first, “Prints in the Age of Photography,” examines the nearly overnight evolution of traditional Japanese woodblock printing in response to the introduction of photography from the West. Its larger sister exhibition, “Photography from the Gloria Katz and Willard Huyck Collection,” features works by groundbreaking 20th-century Japanese photographers, focusing on each artist’s search for a sense of place in a rapidly changing country.

Taken together, these two exhibitions paint a startling portrait of sentimentality and longing, of a country swept immediately and irrevocably into a kind of cultural homesickness.

Printmakers began catering to tourists and foreign clientele who desired nostalgic views of a Japan that was quickly becoming a memory, selling brightly colored prints of rural village scenes to foreigners and Japanese alike.

Printmakers like Kobayashi Kiyochika and Kawase Hasui combined traditional techniques with Western-style perspective, and tackled nocturnal scenes that cameras of the day could not capture. Kiyochika’s nighttime view of the busy Shinbashi train station in central Tokyo, and Hasui’s solemn night scene of a modern steel bridge and rail tracks with a lone rickshaw, juxtapose the modern and the traditional, with a sharp-edged darkness that must be the stylistic forefather of American noir.

From the 1910s on, artists began to defy the traditional Japanese print industry by designing, carving and printing their own works. Called sōsaku-hanga, simply “creative prints,” the movement transformed woodblock prints from a way to transmit information into an art form for personal expression.

Physical and imagined landscapes are deeply rooted in Japanese artistic expression. Through modern woodblock prints, they became a way to reveal an invisible presence, examine change and express longing. Hasui’s “Ferryboat Landing at Tsukishima” offers a portrait of a city built on top of itself, comparing a hulking iron ferryboat with the delicate form of a Japanese sailboat.

Printmaking innovations were also a reaction to the widespread impact of photography, which ultimately led to the collapse of the traditional Japanese woodblock printing industry. Meanwhile, the artists who embraced photography began using the camera to capture their own views of their country in flux.

Landscape views became a popular subject, especially following the devastating Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 and the subsequent reconstruction of Tokyo. Softly delineated subjects and gradations of light and shadow resulted in lyrical, often nostalgic views of a changing environment.

Japanese magazines and newspapers began to revive immediately following World War II, and the photojournalistic approach became paramount. Hayashi Tadahiko, a prominent photographer of this period, published many images of soldiers, street children and life amid burned-out ruins in the streets of Tokyo’s Ginza and Ueno districts.

Photographers also documented the pervasive U.S. military presence, which had a profound effect on Japan. While photographing throughout the country in the 1950s, Nagano Shigeichi caught a dynamic, somewhat disturbing image of children playing near a U.S. military base not far from Mount Fuji.

Tomatsu Shomei began traveling to U.S. military bases throughout Japan in the late 1950s. His images of a child in a seedy part of Yokosuka and of a woman in Nagoya exemplify his visceral approach to capturing postwar life. On his first visit to Nagasaki in 1960, 15 yearsafter the United States dropped a nuclear bomb on the city, he found it “hard to imagine the atomic wasteland.” During subsequent trips, however, he discovered traces of the devastating past in the streets and quiet corners of the rebuilt city.

By the 1950s and ’60s, Western culture was again encroaching on the artistic horizon of Japan, notably the avant-garde. Profoundly affected by Jack Kerouac’s legendary novel of American postwar counterculture, photographer Moriyama Daido began roaming Japan’s highways in 1968, recording his own experiences — whether looking through a car window, walking the alleys of Shinjuku in central Tokyo or standing on a snowy street in his hometown, Osaka.

Western industrialization imposed itself rather mercilessly on many countries throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, frequently leading to the erasure of vast cultural memories. It is remarkable that Japan had such a highly developed artistic and literary culture during its era of Western pseudo-occupation.

No other record like this exists — a native culture overwhelmed by industrialization whose artists articulated the moment so prolifically and with such profound clarity, insight, perspective and emotion. It is overwhelming. It is painful. But it is also extraordinary.