‘Rose Kennedy: The Life and Times of a Political Matriarch’

By • January 9, 2019 0 1263

Reviewed by Kitty Kelley

Anyone who has followed the Kennedys knows the bar is high for books on the subject. Having been inundated for the past 50 years with hundreds of biographies and memoirs and profiles about the spellbinding mystique of John Fitzgerald Kennedy, his family and his thousand days as the country’s first Irish Catholic president, we expect each publication to bring something new and fresh to add to our understanding of the family that refashioned politics in the 20th century.

Serious historians (Arthur Schlesinger Jr., William Manchester, James MacGregor Burns, Nigel Hamilton), journalists (Seymour Hersh, Jack Newfield, Warren Rogers), conspiracy theorists (Jim Garrison), commercial clip-and-pasters (Laurence Leamer, Christopher Andersen) and friends (Paul “Red” Fay, Benjamin C. Bradlee) have tried to capture the firefly magic of the Kennedys, while antagonists (Victor Lasky, Ralph de Toledano) have tried to puncture their myth.

So now comes Barbara A. Perry with “Rose Kennedy: The Life and Times of a Political Matriarch.” Perry promises to deliver “the definitive biography” of the woman whose iron-fisted image-making produced the mystique that continues to endure.

When the John F. Kennedy Library released the papers of the president’s mother (300 boxes) in 2006, Perry, a senior fellow in presidential oral history at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center in Charlottesville, was first in line. Alas, Rose had no secrets beyond the few she revealed in her 1974 memoir, “Times to Remember.” As a biographer, Perry was challenged.

After six years of research and writing, she bowed to the obvious. With nothing new, she went for nuance. Her text is well-written and her bibliography shows research, but there is no gold in the mine.

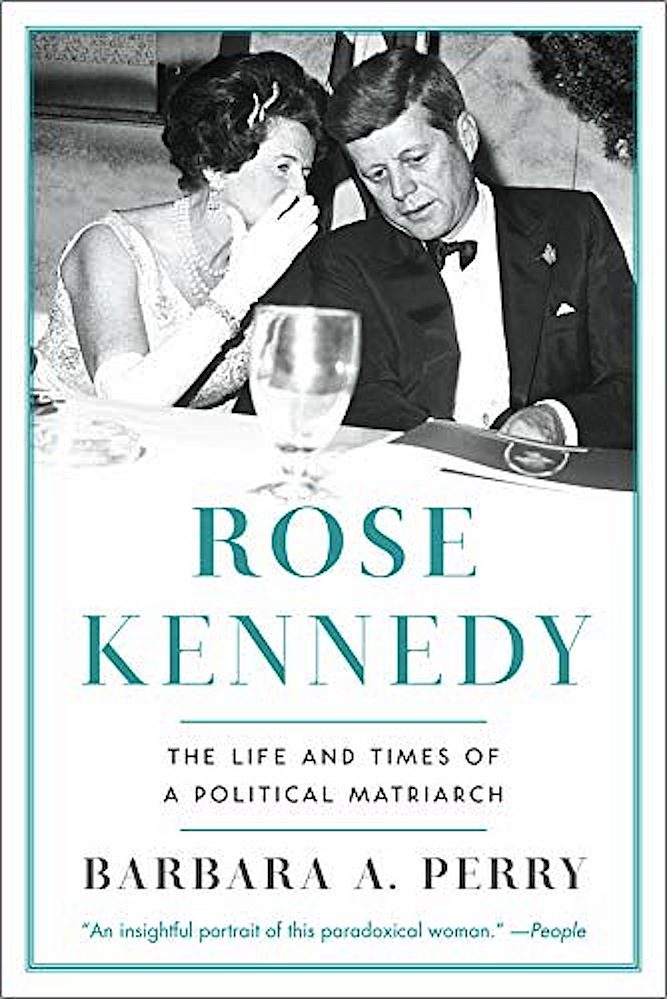

Her book cover, though, is absolutely perfect, because it captures the essence of Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy. The black-and-white photograph shows a woman who later died at the age of 104 after living her life by the black-and-white strictures of the Catholic Church, pre-Vatican II.

Still glamorous at the age of 73, she is sitting next to the handsome president at a White House state dinner in 1963. She is acting as her son’s hostess because the first lady is away on one of her many vacations, similar to the ones Rose took for six to eight weeks at a time to get away from the clamor of her large family — and possibly, according to her biographer, as a means of Church-approved birth control.

Rose is wearing the Molyneux gown she wore when she was 48 and her husband, Joseph P. Kennedy, was presented to the king and queen of England as the U.S. ambassador to the Court of St. James. That was the crowning glory of Rose’s life; to be accepted by British royalty was beyond the biggest dreams of a little girl from Dorchester, Massachusetts.

Bejeweled with two diamond clips in her hair, diamonds dripping from her ears, a triple strand of pearls the size of grapes circling her unlined neck and a bracelet of diamonds wrapped around her arm, which is encased in a long white kid-leather glove, Rose is whispering in her son’s ear. Ever the canny pol, she covers her mouth so the photographer cannot catch a candid shot. (“I do not like candid pictures,” she said. “They are so unattractive.”)

Oh, did I mention that the Molyneux gown was sleeveless? This is a detail Rose would want emphasized, because she prided herself on her petite figure. She frequently said that after having nine children she could still wear a size 8. Her frenetic exercise routine of swimming in the ocean every day, playing golf, walking miles, eating sparingly and rarely drinking had left her sleek and svelte with tanned, taut arms.

Appearances ruled Rose, and nothing mattered to her as much as how one looked — in person and in pictures. She made her children line up for daily inspections so she could see if their shoes were shined and their buttons attached. She saw each child as a reflection of herself and of the family name her husband was making famous on Wall Street and in Hollywood, so she strove for perfection, demanding it of herself and of everyone around her.

A martinet mother, she insisted her children brush their teeth three times a day and say their prayers every night. They were instructed to make meals on time or go without eating, and en route to the dining room they were required to check the bulletin board for the topics of current affairs to be discussed at dinner.

Rose was the parent in charge of their childhood. When they became young adults, her husband took over, but as one daughter said, “Dad gave us many lovely things but mother gave us our character.”

Despite her foibles and her husband’s philandering, Rose relied on her strong religious faith to survive the worst tragedies of her life. She managed to produce an extraordinary family of sons and daughters, who cared for each other, supported each other and remained close throughout their lives — and that is a mother’s finest legacy. Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy is an admirable subject, but one that left her admiring biographer empty-handed.

Georgetown resident Kitty Kelley has written several number-one New York Times best-sellers, including “The Family: The Real Story Behind the Bush Dynasty.” Her most recent books include “Capturing Camelot: Stanley Tretick’s Iconic Images of the Kennedys” and “Let Freedom Ring: Stanley Tretick’s Iconic Images of the March on Washington.”