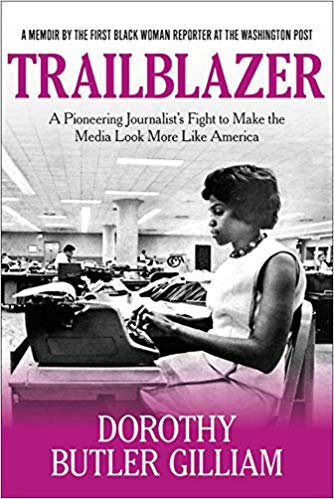

‘Trailblazer’: Dorothy Gilliam of the Post

By • February 20, 2019 One Comment 6301

“I do not recall growing up in fear,” writes Dorothy Gilliam in her new book, “Trailblazer: A Pioneering Journalist’s Fight to Make the Media Look More Like America.”

Now 82 years old, she is the Washington Post’s first black female journalist, hired in 1961 — and on a national book tour.

Of Post publisher Philip Graham Gilliam writes, “Phil made a point of knowing everyone who worked at the paper, especially new employees. He couldn’t miss me sitting at my typewriter on the west wall of the newsroom. Occasionally, when he would stop by my desk, sit on its edge and ask how I was doing … His manner when he spoke to me gave no hint of his illness.” (Graham, husband of Katharine Graham, committed suicide in August 1963.)

Phil Graham was the Harvard Law School graduate who had clerked for two Supreme Court associate justices Stanley Reed and Felix Frankfurter, before marrying Katharine Meyer, daughter of Post owner Eugene Meyer who had bought the paper in 1933 at auction for $825,000. Graham became publisher in 1946, while Katharine was a stay-at-home mom.

Gilliam recalls journalism legend and Post Executive Editor Ben Bradlee, “I wrote a memo to Ben Bradlee … Weeks passed, and I heard no response. Finally, I decided to talk to him about it and made an appointment with his secretary for a meeting. I had to go through the huge main newsroom to his office on the north wall to see him. I felt nervous, even a little frightened, as I walked past the small glass-fronted offices on the right and the rows of desks stacked with paper and occupied predominantly by white reporters on my left. The noise of the newsroom was a low hum of voices, but all was quiet as I entered Bradlee’s office, which was filled with light from many windows.”

Phil Graham hired Ben Bradlee in 1948 as an $80 a week reporter. He also brought on Simeon Booker, the Post’s first black reporter, as well as two other black reporters, Luther Jackson Jr. and Wallace Terry, in the early 1950s. Bradlee quit the Post in 1951 after being denied a shot at a Neiman fellowship by Phil Graham who told him, “Why? You’ve already been to Harvard,” according to Katharine Graham in her 2000 book “Personal History.” He became an information officer at the U.S. Embassy in Paris. After Phil Graham’s death, Bradlee returned to Post triumphantly and between 1965 and 1968 moved from assistant managing editor to managing editor, all the way to the paramount post of executive editor, ostensibly at the behest of Katharine Graham, who was at helm of the Meyer family’s crown jewel — Washington Post.

Between 1963 and 1967, Dorothy Gilliam and her husband, noted abstract artist Sam Gilliam Jr., had three children.

Born Dorothy Pearl Butler in 1936 in Memphis, the eighth of ten children, of whom but five reached adulthood, she grew up in Louisville, Kentucky, and matriculated at Lincoln University in Missouri, and also earned a masters degree in journalism from Columbia University before joining the Post.

As the daughter of an African-Methodist-Episcopal minister, Gilliam stressed the importance of education and faith but missed the opportunity to acknowledge the many union workers in the newsroom during the 1970s. She also failed to mention the union-management minority reporter training program and why Post owners killed it. However, she paid homage to Hollie West, Joel Dreyfuss, Ronald Taylor, LaBarbara Bowman, Michael Hodge, Ivan Brandon, Penny Micklebury, Richard Prince, whose careers at the Post were cut short for no good reason.

The article is both inspiring and reflective of the challenges she faced. The dynamics within the newsroom during that era, as described in her book, shed light on the evolution of diversity in journalism. It’s a testament to her resilience and the strides made, yet the omissions about the union workers and the minority reporter training program underscore the complexities of that transformative period. Her narrative prompts reflection on the progress achieved and the work that remains in fostering inclusivity in media.