Major art museums throughout the country seem increasingly engaged in producing a new breed of exhibitions — shows that introduce audiences to modern and contemporary artists largely unknown to history. In the last year alone, our region has seen Hilma af Klint at the Guggenheim, Charles White at the Museum of Modern Art and Bill Traylor at the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Enter Zilia Sánchez, in an exhibition on view at the Phillips Collection through May 19.

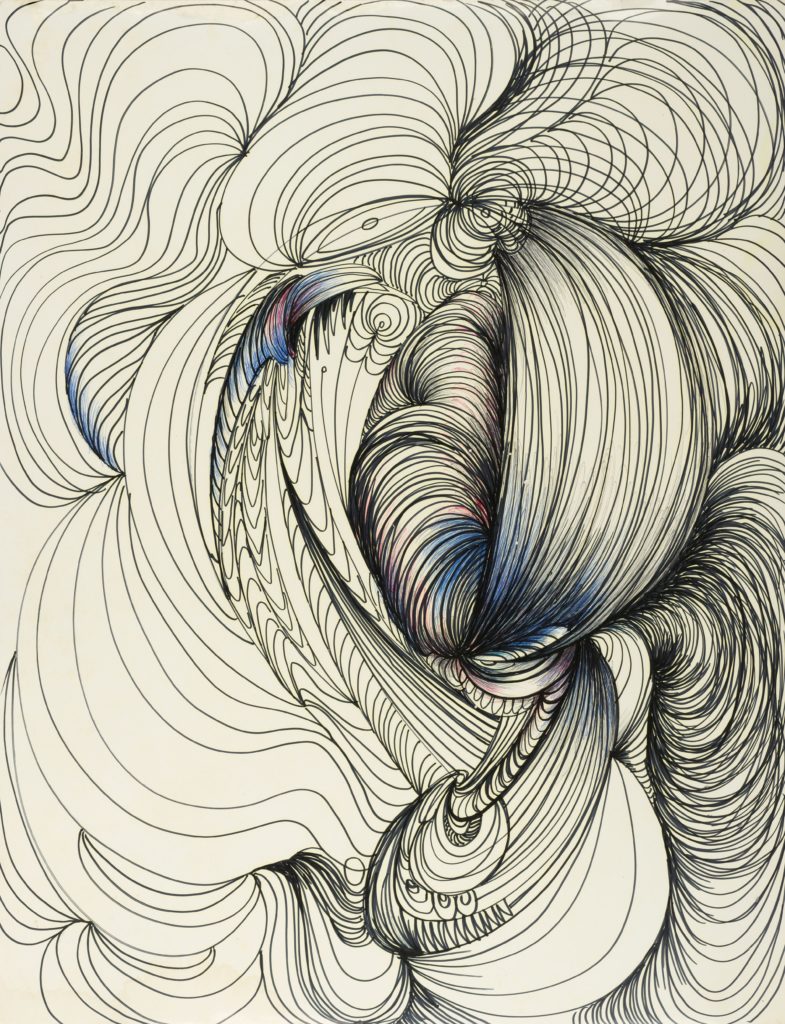

Born in Cuba in 1926, Sánchez has lived and worked in Puerto Rico since the 1970s. An abstract artist who blurs the line between painting and sculpture, she makes work that carries the hallmarks of a regarded lyrical minimalist: stark, soft, biomorphic and undeniably sensual paintings, entirely abstract, in which forms protrude from the canvas like bones and cartilage beneath skin.

Jean Arp, Lee Bontecou and Ellsworth Kelly all come vaguely to mind. Yet Sánchez is not a name that even well-informed contemporary art circles knew until the past few years.

Any good artist’s relative obscurity is a result of infinitely variable causation. Traylor was an outsider who had virtually no contact with the contemporary art world in his lifetime. Af Klint put a moratorium on the exhibition of her work until long after her death. White was not necessarily “unknown,” but grossly overlooked by the modern canon. Sánchez spent most of her developed career seemingly disconnected from the art community.

However, one thing makes itself quite clear: virtually all of these “newly discovered” artists are ethnic or racial minorities or women or both.

For every Mary Cassatt or Helen Frankenthaler in history, it seems there are hundreds of Elizabeth Thompsons (Google her) and Zilia Sánchezes — gifted painters who had the career-inhibiting misfortune of being born women or minorities in the wrong era. By virtue of their circumstances, these artists worked apart from other major artists and did not fit into the prevailing story of their time.

If there is a silver lining, it is that this has made our own time a thrilling and revelatory moment for art and art history. Beautiful voices that had never been heard are suddenly taking center stage.

Sánchez is a welcome addition to this lineup. Her story is unique and her work is deeply of a piece with its era. To see this show is to discover a selection of mid-century masterworks excavated from obscurity.

“I am an Island … The earth and the rocks are solid, but they don’t float. I like to float and feel free.”

This is how Sánchez describes herself, expressing her desire for solitary, uncompromising practice. The exhibition’s title, “Soy Isla (I Am an Island),” appears in many of her works, a metaphor for her experience as an islander, at once connected to and disconnected from the mainland and mainstream art currents.

“Soy Isla (I Am an Island)” is the first museum retrospective of this prolific artist, tracing her career from her Cuban beginnings through her extended visits to Europe and residence in New York in the 1960s and finally to her permanent move to Puerto Rico.

From the outset, Sánchez’s art has been geared toward an abstract language, first bearing aspects of European postwar abstraction. Her own later style of shaped canvases lingers between painting and sculpture. Characterized by reductive, sensuous forms swelling from the wall, and a quiet, disciplined palette of grays, gray- blues and gray-pinks, her canvases suggest both subtle eroticized bodily forms as well as austere topographies.

Her titles frequently reference female protagonists from classical mythology: Joan of Arc, Antigone, the women of Troy. This lends her works a formal and emotional anchor, while the oblique forms float freely in space like islands floating in water.

Sánchez also employs lunar motifs and occasional line drawings throughout her canvases that look like celestial navigation notes derived from a sextant. She says she often draws with her eyes closed as a way to establish balance between her body and mind, her earthly and spiritual influences.

Hurricane Katrina badly damaged Sánchez’s home and studio, forcing her to relocate to a friend’s home. In its aftermath, drawings were her primary means of expression for many months. Yet, as evidenced through her sketchbook diaries, she never stopped working.

Zilia Sánchez, Juana de Arco (Joan of Arc), 1987.

The notion of resilience certainly comes to mind. In the face of natural disasters and cultural roadblocks, Sánchez is an artist with the fortitude, the discipline and the vision to never have stopped. This exhibition certainly offers an exultant moment of vindication. But it is both humbling and inspiring to consider that Sánchez created this work — and would have continued creating this work — even in obscurity. That is the mark of a true artist. And therein lies the real celebration.

May we discover many more like her in the decades to come.