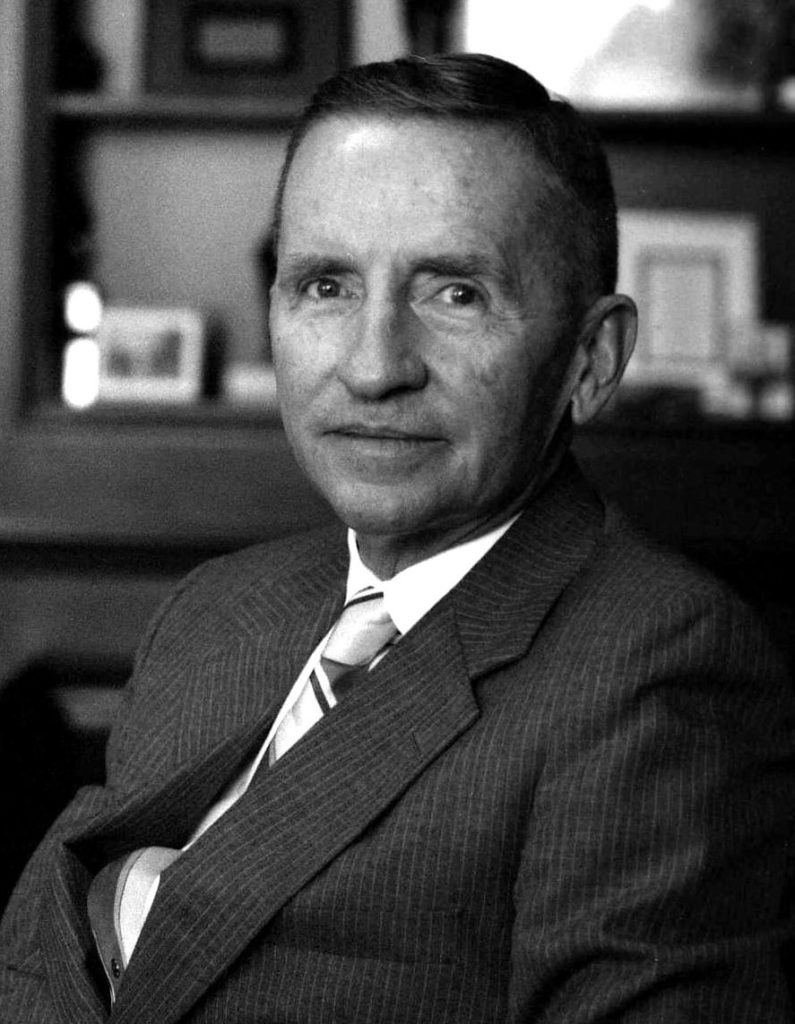

Ross Perot, an American Original

By • July 12, 2019 0 1339

There’s a one- or two-word description, a kind of calcification, that occurs when you peruse the biographical materials, reporting and stories surrounding the life and times of Ross Perot, who died on July 9 at the age of 89 at his home in Dallas.

“Eccentric” comes up quite often, or as per the Washington Post headline, “eccentric billionaire.” While “eccentric” is a live-wire word, and denotes both drama and a little touch of what others might see as wacky or bent, as if he were some financial-political version of Howard Hughes, it does little justice to Perot’s life, which had depth and considerable consequence in the stream of American history.

The bare outline of Perot’s biography misses some essential things about the memories that still flow in the media ozone. Texan is a critical identifier for the man who was born in Texarkana at the onset of the Depression. So was husband, father and family man; he married Margot Birmingham from Pennsylvania in 1956, when he was a midshipman at the U.S. Naval Academy and she was a student at Goucher College in Maryland. The couple had five children and he left behind 19 grandchildren.

You might also want to add Boy Scout and Eagle Scout, and perhaps surmise from his personal life that there was a Norman Rockwell streak in his character, ideals of hard work persevering — and then some — true to beliefs that contained country, family and causes not always verifiable.

After his navy service, he became a salesman for the tech company IBM, where he was gigantically successful. One year, he made the annual sales quota in two weeks. He appeared to recognize the huge importance of technology in the form of computers and all that sprang from them early on, forming his own company, Electronic Data Systems or EDS in Dallas in 1962.

You want impact? EDS computerized Medicare records in the 1960s. When EDS went public in 1968 it went from $16 a share to $160 within days, which led Fortune magazine to call Perot “the fastest, richest Texan.” In 1984, he sold his controlling interest in 1984 to General Motors for $2.4 billion. That was a time, it appears, when a billion dollars was actually worth something.

The business model was: succeed and repeat. He invested in NeXT and its founder Steve Jobs. He founded Perot Systems Corporation, which was later acquired by Dell for $3.9 billion.

He also championed the return of U.S. POWs and MIAs from the Vietnam war, and numerous other causes relating to veterans, some of them conspiratorial and dubious.

He made the 1992 presidential race a three-way race, spurred by his opposition to the Gulf War and his taking a populist role, running as an independent and advocating a balanced budget and opposition to gun control. He often used a phrase from the movie “Network”: “I’m mad as hell and I’m not going to take it anymore.” He called members of Congress “hypocritical bastards” for voting themselves a pay raise.

The race became helter skelter and surprisingly so. Perot cut an unusual figure, thin and short with a high-pitched, Texas-accented voice that nevertheless held its own with President George H.W. Bush and Democratic rising star Bill Clinton.

At one point Perot actually led in the polls with 39 percent. But that did not last, as Perot frequently strayed from his advisors’ advice. Nonetheless, he was also judged the winner of a three-way debate, in which he gave his iconoclastic thoughts on the U.S. Constitution, noting that the Founding Fathers were in the dark about the coming technological age: “There’s lots they didn’t know about. It would be interesting to see what kind of document they’d draft today. Just keeping it frozen in time don’t hack it.”

In the end, Perot received 18.9 percent of the popular vote in the 1992 election, but without a single electoral vote. It likely affected the outcome, but he drew heavily from moderates. It was the best popular vote showing by a third-party candidate since Theodore Roosevelt in 1912.

The war of words over the deficit likely caused Clinton to focus on balancing the budget, which his administration achieved at the end of his term, a singular accomplishment.

Perot tried again in 1996, creating the Reform Party, but achieved only about half the success in terms of votes and was excluded from the presidential debates between Clinton and GOP stalwart Robert Dole.

Upon news of his death, many opined that Perot was the forerunner of the right-wing Tea Party in the GOP and, with his contrarian stances and campaigning style, presaged the rise of Donald Trump, another successful businessman with presidential aspirations.

Be that as it may, Perot wasn’t just a contrarian, or an eccentric or a savvy rich man or a disturber of the political peace, the wackadoo uncle in the attic of American politics. He was, in all of his aspects, an American original.