Kitty Kelley Book Club: ‘1957: The Year That Launched the American Future’

By • April 15, 2021 0 881

Eric Burns writes books with long titles. His first, “Broadcast Blues: Dispatches from the Twenty-Year War Between a Television Reporter and His Medium,” written in 1993, was a memoir of sorts. As an Emmy-winning correspondent for NBC News who later spent 10 years at Fox News (before being fired), Burns knows the highs and lows of broadcasting. He’s since indicated that Fox is not a crucible of credibility, but rather “a cult.”

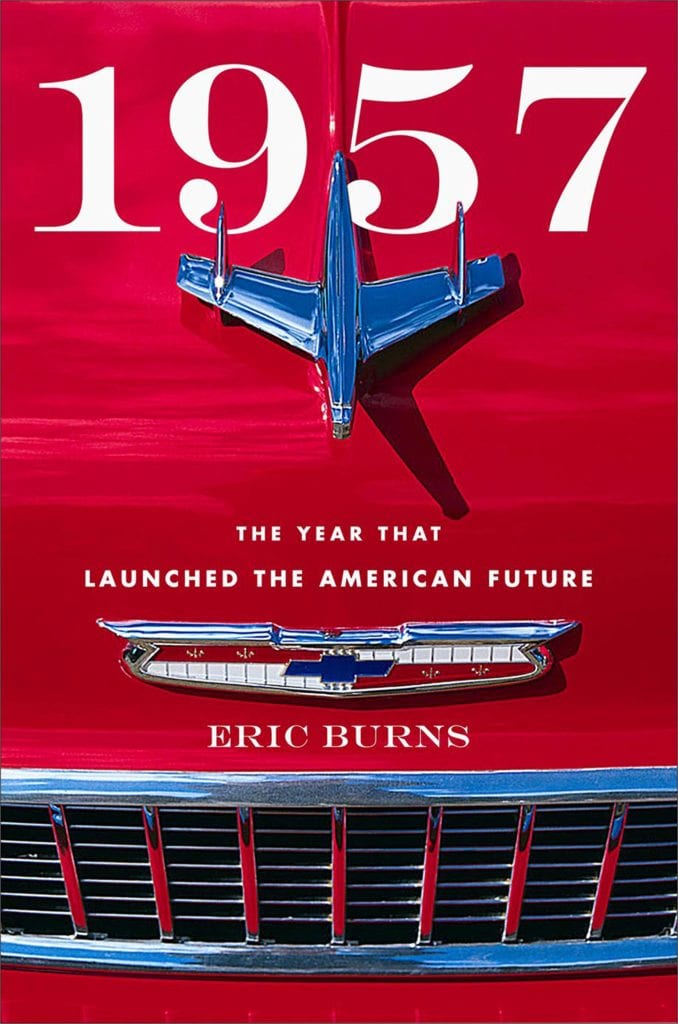

In 2006, he wrote his fourth book, “Infamous Scribblers: The Founding Fathers and the Rowdy Beginnings of American Journalism,” and, in 2010, his eighth, “Invasion of the Mind Snatchers: Television’s Conquest of America in the Fifties.” Now, having tempered his tendency for unwieldly titles, he’s publishing his 15th book, “1957: The Year That Launched the American Future.”

No question that 1957 was a big year. The Ford Motor Company introduced the Edsel, a catastrophe that Burns describes as “the car with the vagina in the grille.” Russia won the space race with Sputnik and President Eisenhower expanded the U.S. with the Interstate Highway Act, an idea he adopted from Germany after experiencing the ease and efficiency of the autobahn. Highways gave rise to suburbs, big cars and a new way of life.

In 1957, Americans were introduced to the Mafia by watching the McClellan Rackets Committee hearings on television. TV also introduced Elvis the Pelvis, Little Richard and the birth of rock ’n’ roll, as well as Joe McCarthy, Fidel Castro, Jimmy Hoffa, Floyd Patterson, Billy Graham and Ayn Rand. The hero of the ’50s — hands down — was Dr. Jonas Salk, who developed the polio vaccine and refused to file a patent to profit from his discovery.

Burns divides his book into five parts, the most important being on race, the cutting issue of our times then and now. In 1957, the country was rocked by the Supreme Court decision known as Brown v. Board of Education, which stated that racial segregation in public schools violated the Fourteenth Amendment. “What happened next resulted in some of the most bitterly poignant tales to emerge … from the tenth circle of hell known as Southern racism,” he writes.

Burns recounts the trauma of nine African American students trying to enroll at Central High in Little Rock, Arkansas. Even decades later, it’s painful to read about white adults spitting race-laden epithets in the faces of the young Black students. Within a week of their enrollment, Congress voted on the Civil Rights Act of 1957, the first such piece of legislation to be approved since 1875, during the Southern revolts against Reconstruction.

But before the vote could be taken, South Carolina’s Strom Thurmond began filibustering on the floor of the Senate, raging against the legislation. He held the floor for 24 hours and 18 minutes, earning himself an ignoble place in the Guinness Book of Records for the longest filibuster in American history. Burns reports the incident in detail, but fails to mention that the feral racist had a Black daughter, having impregnated his family’s 16-year-old maid when he was 22.

For those who have not discovered “The Glory and the Dream: A Narrative History of America, 1932-1972” by William Manchester and just want a cursory gulp of 1957, Burns’s book will suffice; it offers more narrative than an almanac. But be prepared for sentences in need of a stop sign. In a chapter excoriating Ayn Rand, Burns writes:

“The kind of philosopher who so despises Rand, on the other hand, is usually an esoteric sort, like the fellow about whom I recently read who was watching a football game on television when it struck him that, in order to score, Team A has to cross Football Team B’s half of the field, thus sanctifying ‘the property-seizing principle’ of imperialism.”

And, when extolling the 1957 horror film “I Was a Teenage Werewolf,” he writes:

“[Director Gene] Fowler goes on to say that the critics who condescended to review the film, invariably snickering at its simpleminded dialogue and plot devices, not to mention its almost comical special effects, had no idea what the movie was really about and rejected the concept of teenage angst as being just a laughable rite of passage, totally ignorant that the sort of angst that was swelling around them would birth a generation of intensely political angry and aware kids whose minds and hearts would affect the world.”

Burns then writes that the film became “the Edsel of motion pictures.” The same might be said of his book (minus the vagina).

This review originally appeared in the Washington Independent Review of Books.

Georgetown resident Kitty Kelley has written several number-one New York Times best-sellers, including “The Family: The Real Story Behind the Bush Dynasty.” Her most recent books include “Capturing Camelot: Stanley Tretick’s Iconic Images of the Kennedys” and “Let Freedom Ring: Stanley Tretick’s Iconic Images of the March on Washington.” She serves on the board of Reading Is Fundamental, the nation’s largest children’s literacy nonprofit.