May Day 50 Years Ago: The Largest Mass Arrest in U.S. History

By • May 3, 2021 0 4474

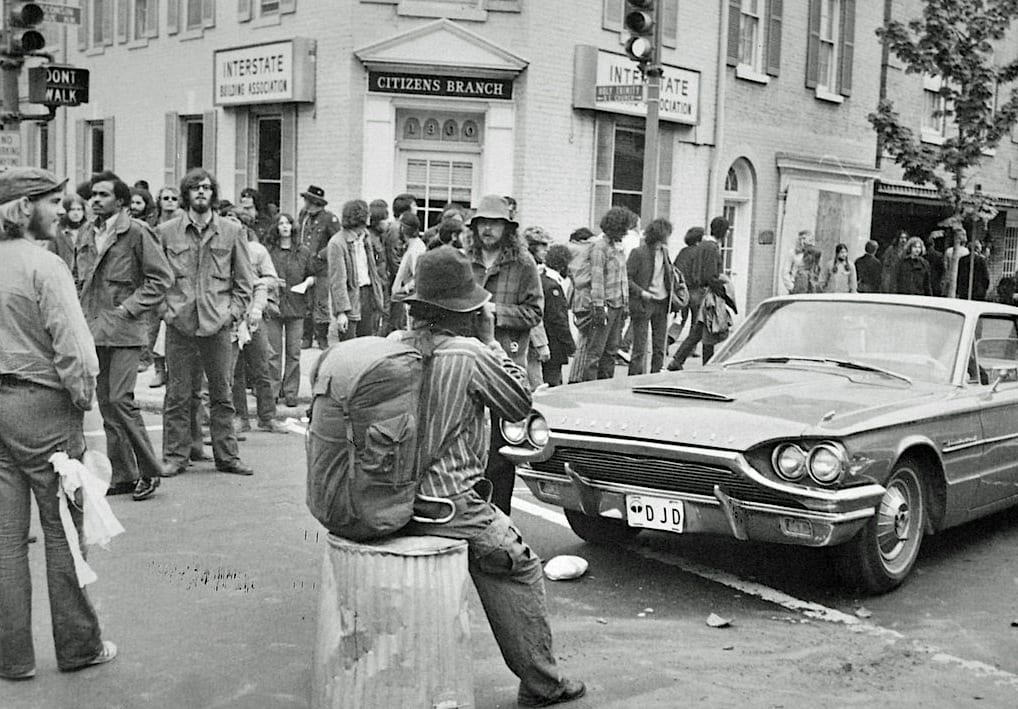

Protests downtown and in Georgetown. Police overreaction. U.S. military on the streets. A nation divided. A president reviled. Democracy under siege. The Capitol earlier attacked.

Marines land at Washington Monument grounds. Courtesy DC Public Library.

It wasn’t last year, but in 1971 across Washington, D.C., during the first days of May. President Richard Nixon’s expansion of the Vietnam War into Cambodia and Laos had galvanized a protest movement that began in the mid-1960s and led to the largest march on Washington and produced the largest mass arrest in U.S. history.

To control the protesters — many of them students and for the most part nonviolent — who were moving quickly from place to place to block traffic, the Metropolitan Police Department wound up arresting 12,000 persons over a period of three days. (Most were released in a day or two without any charges.)

Detention site near RFK Stadium, where neighbors and friends brought food to the captives. Courtesy DC Public Library.

The various groups from the so-called May Day Tribe to the Vietnam Veterans Against the War came to D.C. with the slogan: “If the government won’t stop the war, we’ll stop the government.” Protesters were intent on shutting down bridges, intersections and building entrances to disrupt the federal government.

Today, this massive event is little known and dimly recalled. One commenter called May Day 1971: “The most influential protest you’ve never heard of.”

Luckily, journalist Lawrence Roberts recently authored “Mayday 1971: A White House at War, a Revolt in the Streets, and the Untold History of America’s Biggest Mass Arrest.” His book is rich in details about the largest act of civil disobedience in U.S. history. The spring protests against the Vietnam War, Roberts says, “bequeathed consequential changes to American law and politics. They set lasting precedents for individual rights in the heat of dissent, including rules for protesting today in the heart of Washington, D.C.”

As a 19-year-old college student, Roberts himself was part of the police dragnet, getting arrested near George Washington University. He sees the Spring Offensive, as the protesters called, kicking off on March 1 with the Weather Underground’s bombing of the U.S Capitol. (The bomb damaged the Senate barber shop; no one was injured.) The author looked at all those involved — D.C. officials, such as Police Chief Jerry Wilson, White House advisors, national guardsmen, college administrators, demonstrators and protest leaders, such as Rennie Davis. He saves his greatest admiration for the public defenders — “they saved democracy” — who assured that the mass arrests were seen as illegal and unconstitutional. Indeed, lawsuits later netted payments to those detained.

David Roffman, then publisher and owner of The Georgetowner, recalls guardsmen at the corner of 28th and M Streets, where the newspaper office was located, and guardsmen lined up along Key Bridge as he drove to work. “It was all quite a sight. The police parked their vans at the intersection and simply arrested the kids as they entered Georgetown from downtown,” Roffman said. “Brandishing his firearm, one cop or guardsmen yelled at me to get inside when I peered out the office window with my camera.”

Meanwhile, as Georgetown trash cans were being flung about and its main intersections blocked, Georgetown University invited protestors, who needed a place to stay, to camp on its sports field. Of course, that attracted more police — and tear gas — making a mess on campus and jamming adjacent streets.

The entrance to Georgetown University at 37th and O Streets NW. Courtesy GU Library.

“There were many arrests on the streets of Georgetown that weekend,” Chris Murray, Georgetown alum and owner of Govinda Gallery, told The Georgetowner. “It was a weekend where it became apparent that more and more people were mobilizing to stop the illegal war and to get rid of Richard Nixon and his crew of war mongers.”

“May Day 1971 was one of many turning points against the War in Vietnam, and that weekend the village of Georgetown played a major role in raising the consciousness of people against the illegal war.” (Read Murray’s complete comments here.)

Georgetown University, as seen from Arlington. Courtesy GU Library.

Guardsmen on the 1400 block of Wisconsin Avenue NW. Courtesy DC Public Library.