Knowing and Celebrating Georgetown’s Black History

By • February 9, 2022 0 2222

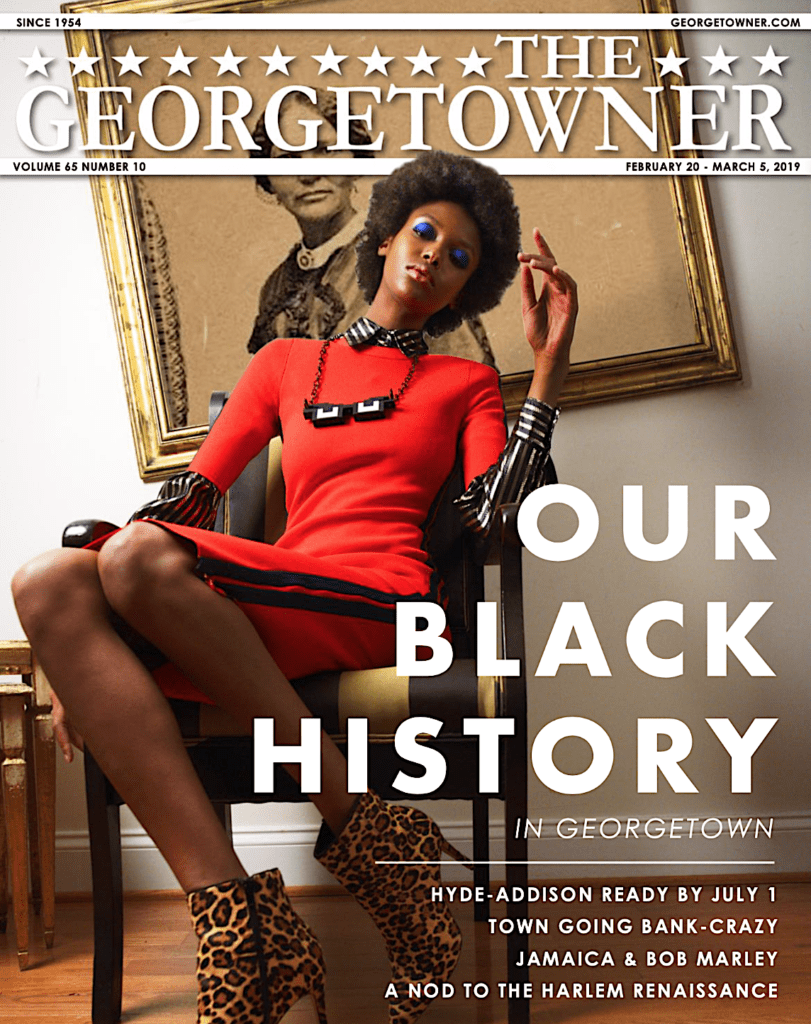

Thirty years ago, The Georgetowner hosted a reception for a book that helped the town rediscover part of its past. “Black Georgetown Remembered” is now a classic of Black history in Washington’s oldest neighborhood. It was published by Georgetown University Press in 1991 with the subtitle, “A History of Its Black Community From the Founding of ‘The Town of George’ in 1751 to the Present Day,” and has gone through several reprints. The book prompted many talks and additional interviews. It records the tales of Black families recalling their homes and blocks of Georgetown — consistently one-third Black until around the Second World War. Gentrification came first to Georgetown in all of D.C. It’s a surprising story of African American life, and those who remain tell this part of everyone’s history more vigorously today. Tonight, the Citizens Association of Georgetown is offering a program on “Black Georgetown Remembered.”

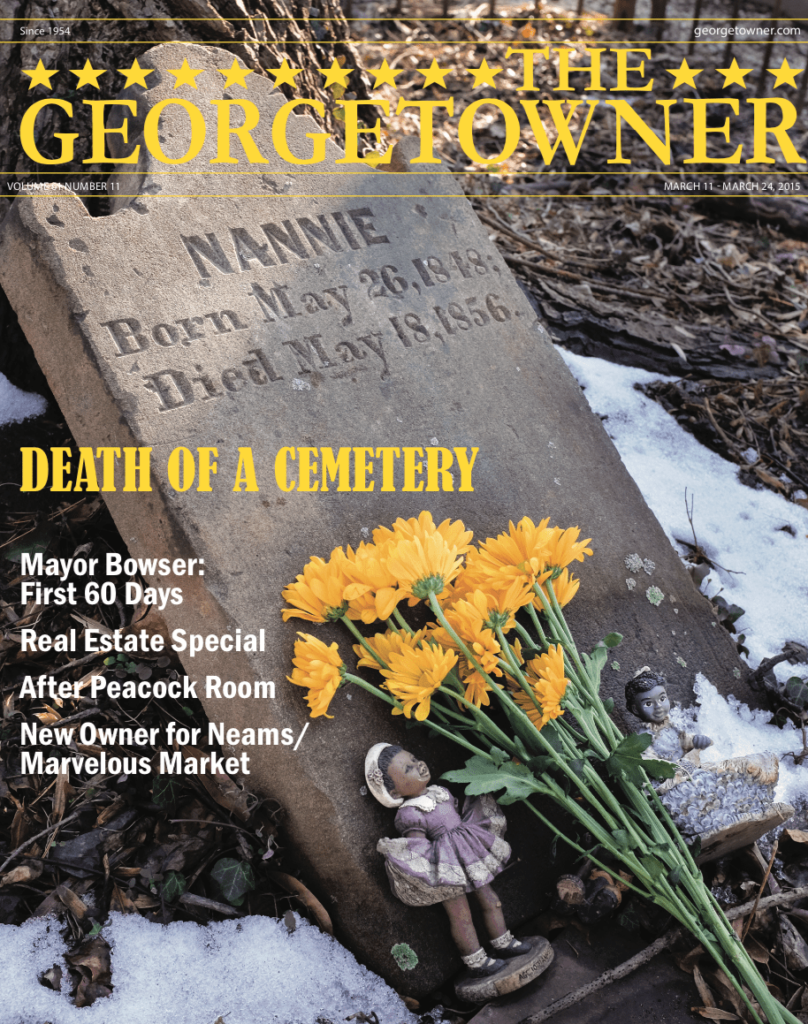

The graveyard at 27th & Mill Road, bordering Rock Creek Park, Oak Hill Cemetery and Dumbarton House, the Mount Zion and Female Union Band Society Cemetery is slowly but surely being changed to a proper memorial. In March 2015, a Georgetowner cover story called attention to the plight of this long-neglected place, one of the oldest African American burial grounds in Washington, D.C. With people like Neville Waters, Thornell Page and Lisa Fager, a nonprofit ensures the cemetery’s preservation and commemoration. “One of the things I have enjoyed, even to this day, is the communal feeling in Georgetown. We’re still close-knit, even though our numbers have dwindled,” Waters told us.

The Georgetown African American Historic Landmark Project continues its installation of bronze free-standing plaques with posts at various locations around town. Last week, the Georgetown-Burleith Advisory Neighborhood Commission voiced its support of the project. More than 80 markers are slated for the historical tour. The project’s mission statement casts a wide net: “To honor together the enslaved and free African Americans who worked in, lived in and built Georgetown; to celebrate together their resilience, strength and fortitude; to promote together accurate African American and American history preservation; to start a dialogue of reconciliation which eliminates any shame, guilt or humiliation; and to foster a commitment to lasting changes.” We applaud Andrena Crockett for her vision and deep commitment.

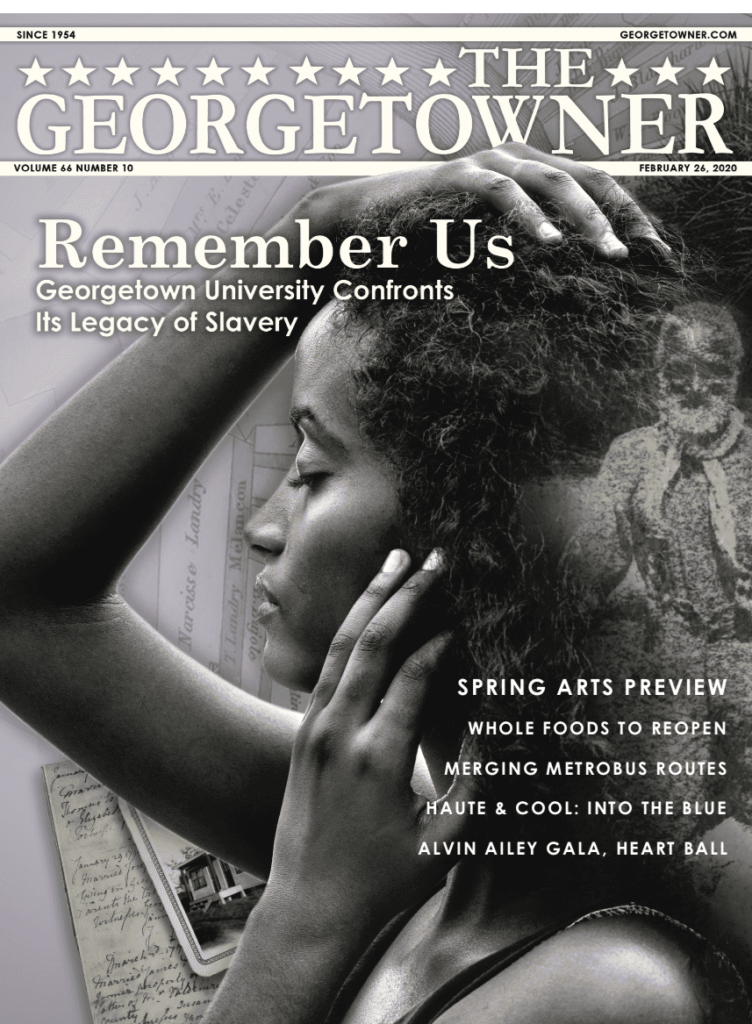

One of the lightning rods of memory has been Georgetown University’s confrontation of its slavery legacy. “It seems to me that the story of Georgetown and slavery is a microcosm of the whole history of slavery,” said Professor Adam Rothman, a member of Georgetown University’s Working Group on Slavery, Memory & Reconciliation, in 2016, regarding the university’s connection with the Jesuits’ 1838 sale of 272 slaves.

Since then, the university has apologized for arranging the sale of enslaved people from D.C. and Maryland farms to help pay off debts. It renamed two main campus buildings: for Isaac Hawkins, the first slave listed on the sales document; and for Anne Marie Becraft, who founded a school nearby for black girls and later became one of America’s first Black nuns. G.U. has offered descendants of the 272 slaves, most of whom ended up in Louisiana, legacy status in admissions.

Fifth-generation Washingtonian, P Street resident and educator Monica Roaché — former advisory neighborhood commissioner and now a D.C. Democratic Party Secretary — reminded us a few years ago: “The African American community contributed to Georgetown. There were doctors, lawyers, educators and more.”

Georgetown University Professor Marcia Chatelain told us: Washington, D.C., is a place with Black history that has shown “great beauty and inequality. It is a sober reminder and a celebration, too, of achievement and strengths.” She added: By knowing and understanding history, Americans have a chance “to demonstrate what’s possible” — constructing “a well-rounded account.” Black History Month is a time “to be reflective.”

To be sure, we all can reflect on many Black Georgetown names: Yarrow Mamout, Alfred Pope, Hannah Cole Pope, Robert Holmes, John Ferguson, Moses Zacariah Booth and Elizabeth Oliver Booth, Georgetown University President Patrick Healy, tennis doubles champions Roumania and Margaret Peters, Doctors C. Herbert Marshall and Joseph Dodso. Of course, there’s more — and more learning to do.

The cover of the March 11, 2015, Georgetowner: “Death of a Cemetery.”

The cover of the Feb. 26, 2020, Georgetowner: “Remember Us — Georgetown University Confronts Its Slavery Legacy.”