Picasso: Painting the Blue Period, at The Phillips Collection

By • March 9, 2022 0 1965

Pablo Picasso was a painter. However, the reason we know his name is because at some point he came to represent something more than his work. I have never walked into a modern art museum that didn’t have at least two Picasso’s on view. I don’t think I’ve ever engaged in a discussion about the history of art that did not at some point drop his name as a point of reference.

Picasso is the immortal sovereign of a small, crowded and highly contested territory in the domain of Western culture. He controls the passageway that connects the old world and the new.

Like any beloved monarch, Picasso is despised by the cognoscenti and accused of a litany of legally nonbinding offenses by most who knew him. There are parties who contest his authority. They submit worthy rivals to challenge him — usually Cezanne. (Picasso, for the record, worshipped Cezanne.) But Picasso cannot be overthrown because he is anointed by popular consensus. He is widely adored by the public — by regular people.

For my part, I’m indifferent to the issue of whether Picasso is the greatest painter of all time or a shrewd and ruthless megalomaniac who caught the last perfect wave of history, but it’s pointless to deny his cultural supremacy. He is ubiquitous. He is a noun.

The heaviest critique leveled against Picasso is that he copied the genius that surrounded him and claimed it as his own. It’s always been a well-known secret that Picasso was a flagrant plagiarist. He often admitted it. He spoke about it with impish amusement, famously saying, “Bad artists copy, good artists steal.”

I find the criticism to be sort of ironic because it was precisely his genius for visual appropriation that sustains his legacy. The critique, I think, goes something like this: All Picasso really did was synthesize Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance, Neoclassical, Post-Impressionist and Fauvist influences with traditional African, Iberian and non-Western art to create a unique and joyous visual language that appeals to everyone from Arab Sheikhs to nine-month-old babies.

So perhaps this is why, despite the radically shifting priorities of the art world, museums can’t stay away from Picasso, and neither can the artgoing public and neither can I.

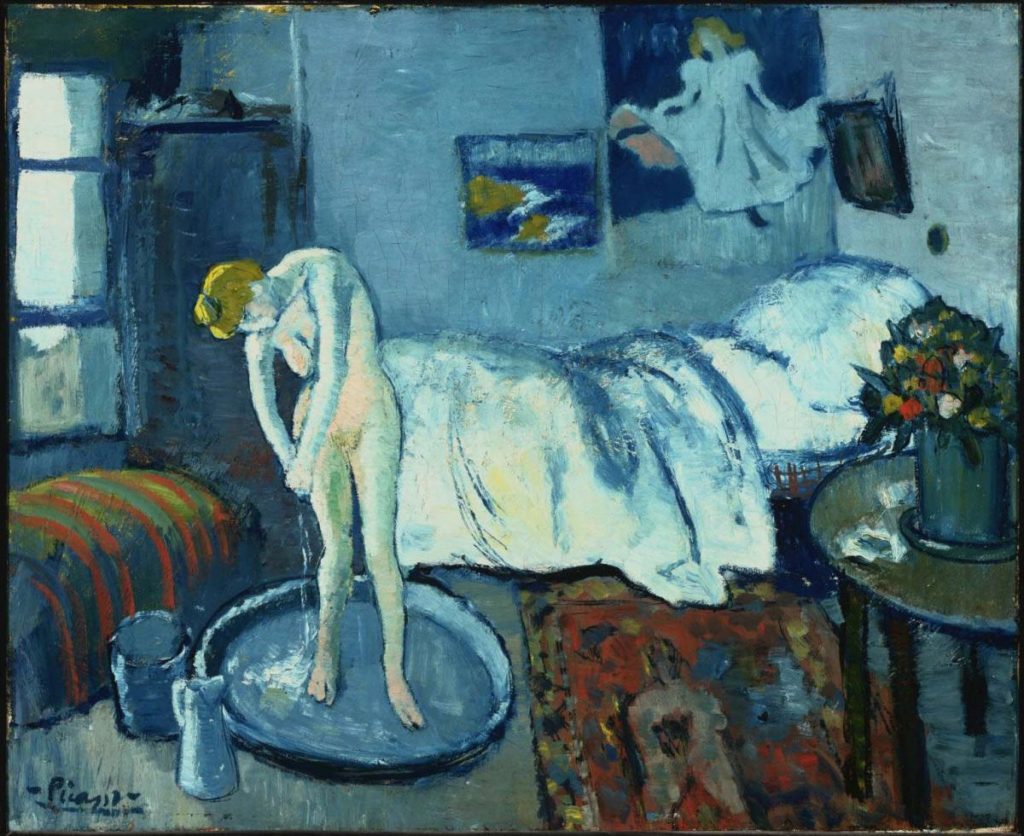

At the Phillips Collection through June 12, Picasso: Painting the Blue Period focuses on the years 1900-1904 — the artist’s early twenties — following the young Spanish painter as he formulated his signature Blue Period style by engaging with the artwork he encountered by Old Masters and his contemporaries as he moved between Barcelona and Paris. The exhibition explores Picasso’s evolving and sometimes controversial depictions of sex, class, poverty, charity, family and even female incarceration.

What this exhibition makes clear is that Picasso wasn’t really a stylistic thief — he was more like a sponge. He did more than just copy people. He filtered everything he saw compulsively through his own hand. Most of the paintings in this exhibition look like they were team-painted by Daumier, Toulouse Lautrec and El Greco, with strange but undeniable hints of Japonisme. To that extent, he was like the perfect art student, which on some level foreshadows his astounding success. Throughout his career, he was always seeing things anew, always exploring new ideas, always evolving, and yet it never seemed like he was working that hard.

Prior to this exhibition, I had never thought about how young Picasso was when he painted his Blue Period works, but it now seems glaringly obvious. So much of this work is contrived, moody, vain and conceited. It smacks of youth. This isn’t to say it’s bad. He had such a deft touch and mature taste that he could make his sophomorically self-serious depictions of heartache and societal desolation look good — often beautiful.

The exhibition culminates in Picasso’s emergence from the Blue Period into the Rose Period. As the final gallery makes clear with a collection of sun-bleached, blush-toned figure paintings, what begins as the exploration of an alternative color palette quickly transforms into an explosion of creative energy that invents Cubism and lays the foundation for art in the modern era. He was 25 years old. One year later he would paint Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. The rest, as we know, is art history.

Don’t miss this show. It’s a gem.

“Picasso: Painting the Blue Period “will be at the Phillips Collection through June 12, 2022.