Community Grieves Desecration of Child’s Grave at Georgetown’s Oldest Black Cemetery

By • June 22, 2023 7 3916

Just after Mt. Zion Cemetery-Female Union Band Society Cemetery held Juneteenth celebrations to commemorate the national holiday on Monday, June 19, for the liberation of the enslaved, terror struck on the sacred grounds of one of Washington, D.C.’s oldest Black cemeteries.

The site of frequent gifts, tokens, dolls, antique toys and well-wishing notes from visitors, the much-beloved headstone of “Nannie,” believed to be a 7-year-old African-American girl buried in 1856 on the grounds at 2501 Mill Road NW, Georgetown, was desecrated by fire.

Before-and-after photos of Nannie’s headstone site were featured prominently on the Black Georgetown Foundation’s Instagram site, along with The Georgetowner’s Juneteenth story, followed by the Washington Post’s article from the evening of June 21, “Someone burned a beloved child’s grave in a historic Black cemetery.”

“Strangers have carried toys into one of the oldest Black cemeteries in the nation’s capital and placed them near the grave marker of a girl who lived long ago and not long enough. They brought them for Nannie, and for years, to the amazement of people who regularly visit the cemetery, many of those gifts remained undisturbed,” the Post reported following the fire.

Nannie’s gravesite desecrated by fire. Courtesy Black Georgetown Foundation.

According to the Post, Lisa Fager, executive director of the Black Georgetown Foundation, the non-profit restoring and caring for the historic cemetery dating to 1808, discovered the site of the desecration early Tuesday morning, the day after the cemeteries’ Juneteenth celebrations which had brought crowds to the site. Fager was leading a group of George Washington University students “ to Nannie’s marker” when “she found that someone had set the site on fire.” And, “instead of toys and cards, she saw melted plastic and blackened stone.” When she took in what had happened, “she screamed,” then “cried.” And “hours later, she was still trying to process what she saw.” She wondered, “It’s a child’s grave, who would do that?”

Fager often prompted visiting students and others about research questions related to Nannie’s gravesite. Was she free or enslaved? Who paid for her Virginia bluestone tombstone (more expensive than what might have been expected)? What was Nannie’s life and community like in Georgetown before the Civil War? What was it about Nannie’s headstone that drew visitors so often to offer gifts and tokens?

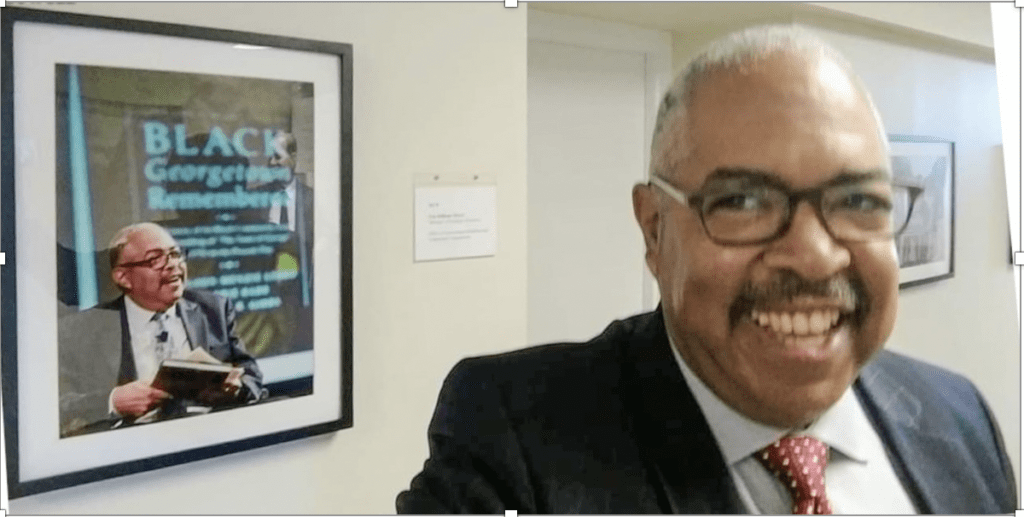

The Georgetowner spoke with Neville Waters III, president of the Black Georgetown Foundation about the desecration of Nannie’s beloved site. In his 2022 Mapping Georgetown story Waters recalled his family’s deep roots in Georgetown and especially with its historic Black cemeteries: “My family roots in the Georgetown community are broad and deep-extending throughout multiple generations and locations including the Mt. Zion-Female Union Band cemeteries. The sacred space is the burial site of my great great grandparents – Hezekiah and Martha Turner – and their sons Charles (my great grandfather) and James. The property also served as a refuge on the so-called “Underground Railroad” with the crypt used for that purpose still standing along the hill overlooking Rock Creek which follows the path to freedom for those fleeing enslavement. Learn the stories and share your support.”

Neville Waters III at Georgetown University’s front office on the occasion of speaking about the book “Black Georgetown Remembered.” Courtesy photo.

We asked Waters what makes the desecration of Nannie’s grave so particularly horrific.

“What’s disturbing is the act of vandalism on such a sacred area. It certainly suggests some potential for a specific hate-crime…. But even if it’s not, it’s still a horrific act…. It’s disappointing that that’s an element of our society that still feels the need, or the desire, or the insecurity, or the hate, or whatever it is that motivates them to do something…. so cowardly…. And it’s hard to feel that it’s just a coincidence that this incident would happen the night after having such a wonderful event around Juneteenth, so it would seem to be a connection. So, again, it’s just an horrific incident.”

But the crowd of people who turned up this morning at Nannie’s headstone to bring solace, to offer flowers, tokens, gifts, thoughts and prayers is encouraging.

“I’m encouraged to see the response from the community that they wanted to show their support in general for the cemetery but also specifically for this young lady whose resting place has been desecrated,” Waters said. Rather than being intimidated, he suggested, people are coming up to Nannie’s site to “leave gifts and acknowledge that we’re not going to be deterred – and that’s very encouraging and heartening.”

Visitors pay respects to the desecrated headstone of “Nannie” on Thursday morning, June 22. Photo courtesy Neville Waters.

Waters hopes that Georgetowners understand the magnitude not only of what happened to Nannie’s tombstone site, but of the significance for the historic cemetery itself. “Beyond the fact that this is the oldest Black cemetery in Washington, D.C. – which frankly, [should be enough] in terms significance – But the fact that it’s a designated UNESCO site due to the presence of the burial crypt which served as refuge on the Underground Railroad and due to the fact that there are individuals buried there who made contributions not only to the development of Georgetown but to [Washington, D.C.] and beyond.”

Visitors showing support at Nannie’s tombstone Thursday morning, June 22. Photo courtesy Neville Waters.

Due to historical prejudice, the once all-White (but no longer) Oak Hill Cemetery next door garnered more official attention and support over the years than has the marginalized Mt. Zion Cemetery-Female Union Band Society Cemetery adjacent to its lush grounds, Waters said.

“You know the stark contrast between its neighbor Oak Hill [cemetery] is just a clear demonstration of the impact of systemic racism,” Waters said. “It’s not just an individual person that takes it upon themselves to do something but the system is managed in a way that’s unfair over time that has a severe impact, whether it’s the cemetery or other cultural aspects of lifestyle, wealth, or health — it’s part of our history, and a sad part of our history. When we allow things in our past to either be ignored, whitewashed, or otherwise destroyed, to me that feels like a tragedy in and of itself.”

Going forward, Waters would like to see Georgetown’s residents show greater respect by not, for example, walking their dogs on the “sacred grounds of the cemetery,” and by better understanding, appreciating and supporting efforts to protect and restore sites of significance to Georgetown’s and the nation’s Black history.

For more information on the Mt. Zion Cemetery-Female Union Band Society Cemetery and the Black Georgetown Foundation go to Mtzion-fubs.org.

How thoughtlessly careless of this article and its author to refer to Oak Hill

Cemetery next to Mount Zion as “all white” IN THE PRESENT TENSE. That may have been the case a hundred years ago, but not now. Those days are long gone. Both the author, and the Georgetowner newspaper which published (and SHOULD have better edited) the article before printing it, owe Oak Hill Cemetery a published apology.

MARC: Your point is accurate. We know Oak Hill well and erred in our editing. We have revised the article.

— Robert Devaney, Editor-in-Chief

Actually, the original phrasing in the piece contextualizing what Neville Waters was about to say referred to Oak Hill Cemetery in the following way: “Due to structural racism and prejudice, the historically all-White Oak Hill Cemetery nextdoor…” By “historically,” I meant in the PAST. Just as I would refer to an “historically Black college or university” (HBCU) as one which was originally based on a segregationist social order but today obviously accepts students of all races, ethnicities, etc., even though it’s an “historically Black” college or university. Clearly, according to Oak Hill Cemetery’s own website account of its historical background, Oak Hill Cemetery was founded prior to the Civil War in a segregationist society and its subsequent development adjacent to Mt. Zion Cemetery played out in the context of White/Black inequalities. On this matter, both Neville Waters III and Oak Hill Cemetery are in agreement.

This is newsworthy but I am imagining the criminal(s) who set the fire may enjoy seeing their work “in lights”. The thought disgusts me, and I would have liked to have seen something in the article — even a mention — about police involvement and investigation, for the sake of the community who cares for and admires the cemetery, as well as to scare the criminals.

I’m the Executive Director of the Black Georgetown Foundation, which stewards the Mt Zion–Female Union Band Society Cemeteries. I re-read this article after it unexpectedly popped up on my screen this morning and wanted to respond to your comment because you raised an important point.

The laws around grave desecration vary dramatically across the region. In Virginia and Maryland, it’s a felony. In the District of Columbia, the penalty is a $100 fine. With consequences that minimal, it’s difficult to expect meaningful accountability or resource allocation.

I haven’t done the historical/legal research yet, but it would be interesting to understand why DC’s law is so out of step with our neighboring jurisdictions. It may stem from DC’s long history of not being a state and Congress’s control over our criminal code for generations.

It’s definitely something worth revisiting — not just for our cemeteries, but for historic burial grounds across the District.

Good point. Given the fast-breaking aspect of this story, I was unable to hear back from the spokesperson for Mt. Zion by publication time. She was being interviewed by NBC News. Stay tuned for developments on this important story, however. Thanks so much for your feedback!

thank you for the article