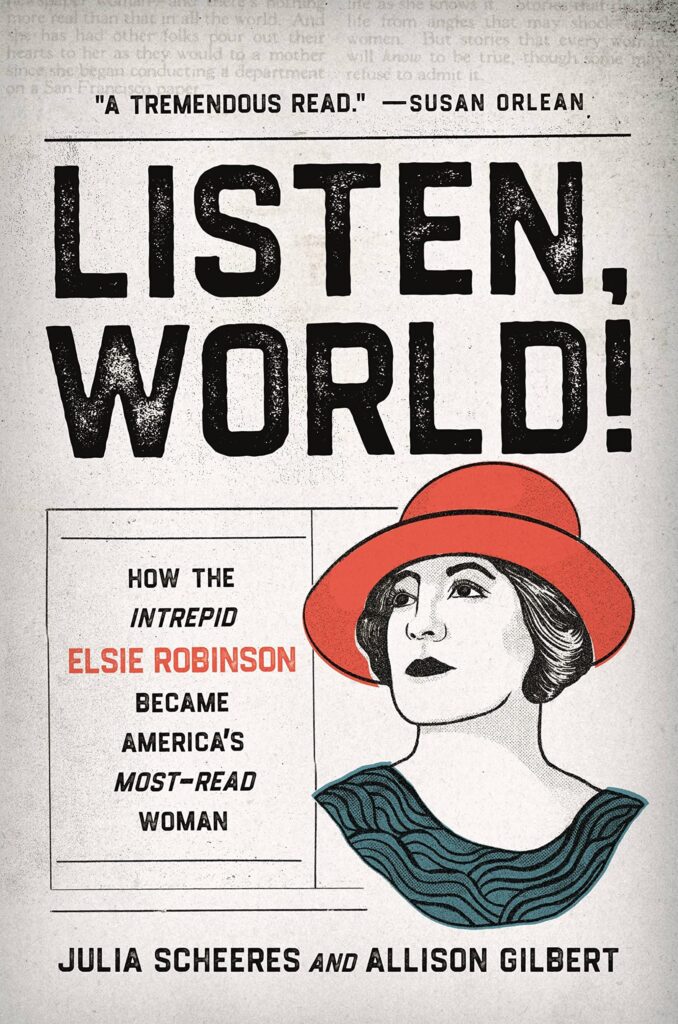

Kitty Kelley Book Club: ‘Listen, World! How the Intrepid Elsie Robinson Became America’s Most-Read Woman’

By • August 16, 2023 0 1688

Remember that iconic scene in “The Mary Tyler Moore Show”? Mary’s editor, Lou Grant, played by Ed Asner, says, “You know, Mary. You’ve got spunk.”

She beams. “Why, thank you, Mr. Grant.”

He growls. “I hate spunk.”

Lou Grant would’ve been brought to his knees by Elsinore Justinia Robinson, who was spring-loaded with spunk — hell-bent, fire-popping spunk. As the highest paid female columnist for Hearst newspapers, she was syndicated to 20 million readers and wrote like a rocket, filing over 9,000 stories in 40 years. A passionate autodidact, she also wrote poetry, short fiction, and essays, and published many children’s books that she illustrated herself. In 1934, she wrote her memoir, “I Wanted Out.”

Yet for being one of the most famous people in America, Elsie Robinson was virtually forgotten after her death in 1956. Now, decades later, we have the first biography of this female phenom, described by her biographers as an “all-around badass!” Julia Scheeres and Allison Gilbert spent more than 11 years researching and reporting to write “Listen, World! How the Intrepid Elsie Robinson Became America’s Most-Read Woman,” the life story of this life force.

Born in 1883, Elsie grew up in Benicia, California, a small town which “permitted uncorked hedonism,” and where F Street divided the community. Downtown was “saloons … and sporting women.” Uptown was churches and knee-bending nuns. Elsie lived uptown — the “good” side of town — near the high stone walls of St. Catherine’s Convent, but she prized downtown.

“Goodness, though it promised halos in heaven, certainly didn’t offer a lively gal many breaks on earth,” she wrote in her memoir. “Bad Women, on the contrary, had practically unlimited freedom and fun.”

Elsie was a “lively gal” times 10, a free spirit from the West as unsinkable as Molly Brown, and as uncorseted by social strictures as Annie Oakley. When Christie Crowell, a widower from the East who’d traveled to California after the death of his young wife, first met Elsie, he was captivated by her enthusiasm. Soon, he proposed, and she accepted.

He happily wrote to his parents with the news, but they responded with grave reservations. They felt their already-shaky social status in Brattleboro, Vermont, would not be enhanced by a young woman from a working-class family in the town that spawned the California Gold Rush, hardly a citadel of moral rectitude. So, they did all they could to dissuade their son from pursuing the marriage.

“After months of epistolary discourse, the Crowells set down their terms,” write Scheeres and Gilbert. “Christie could marry Elsie on one condition: she must attend a seminary school to learn household management, elocution and the Bible … to become a fitting bride for their son.”

You might think that, at this point, the high-spirited Elsie would tell Christie and his parents to stuff their seminary school, but in the early 1900s, a young woman’s options were severely limited — either marry or mildew — so Elsie agreed to their terms. As she would later learn, however, even a married woman’s status was no higher than the family dog’s. She stayed with her husband for nine years, until Christie demanded a divorce on the only grounds available — adultery. Reflected Elsie:

“So solemn was marriage, so shameful divorce that the thought of separation had never as yet crossed my mind. Someday it will seem incredible that any woman should have faced such shame, such deliberate torture as I was about to face.”

On almost every page of this engaging biography, the authors weave in bits of Elsie’s writings, putting her opinions and insights into italics so the reader knows exactly what was on her mind. They don’t have to speculate about how Elsie felt living in the same house with her snooty in-laws; they have her diaries, interviews, letters, and newspaper columns to tell them. Yet even with such a cornucopia of information, the authors still insert “might have felt,” “surely thought,” and “was likely oblivious” here and there, sprinkling “perhaps” and “presumably” throughout their presentation of this fascinating woman who survived every obstacle she ever met.

The highlight of Elsie’s life was the birth of her only child, George, who suffered from severe asthma attacks, forcing him to miss weeks of school. In 1926, the young man found a small lump in his foot that was surgically removed. But after being released from the hospital, he was wracked by fever, chills, and severe chest pain. Elsie wrote a column filled with her anguish:

“I’m afraid … Fear runs through all my life. I cannot mark its course with a definite line, but its grim shadow tinges my brightest moments and noblest dreams … I have only found one way to manage fear… Go on! No matter how terrible your inward agony, go on! Don’t wait until the darkness lifts. Grab each small task, whether it appeals or not! Keep doing something! Go through the gestures of normal life! Eat, talk and smile as though all things were well. Then gradually your inner body will conform to your firm fighting front. Your thoughts will cease their maddened hammering at your skull. You will not banish fear, but you’ll have conquered it and made it run to heel.”

Hear, hear, Elsie!

George Alexander Crowell took his last rasping breath at age 21 with his mother by his side. Elsie tried to outpace her unmanageable grief with round-the-clock work. “There are no details when the thing you have loved best goes on. Only a wailing, witless darkness… the sense of utter bankruptcy.” In 1928, the 48-year-old Elsie finally buckled to the unmitigated pain and suffered a nervous breakdown.

Throughout her life, Elsie Robinson used her national platform to express her increasingly progressive views. She supported labor unions; she ridiculed Prohibition; she denounced the death penalty. During the 1930s, she railed against the Nazis and rallied Americans to support Jewish refugees. She condemned racism and excoriated the Daughters of the American Revolution for refusing to let Paul Robeson perform in their concert hall.

“And on what, may I ask, do you base your supremacy?” she wrote in her syndicated column. “You didn’t choose your ancestors …You happened to be born white … you could have put aside ignorance and prejudice and contemptible snootiness … and given your lives for unity. But you weren’t big enough. You weren’t brave enough.”

God bless you, Elsie!

“Listen, World!” is a glorious biography for all the women who deserve to see themselves on life’s pedestal — and for all the heroic men who help lift them up.

Georgetown resident Kitty Kelley has written several number-one New York Times best-sellers, including “The Family: The Real Story Behind the Bush Dynasty.” Her most recent books include “Capturing Camelot: Stanley Tretick’s Iconic Images of the Kennedys” and “Let Freedom Ring: Stanley Tretick’s Iconic Images of the March on Washington.” She serves on the board of BIO (Biographers International Organization) and Washington Independent Review of Books, where this review originally appeared.