Black History: Casting Back a Century in Washington, D.C.

By • January 29, 2024 0 2511

Today, February 1, we joyously celebrate the start of Black History Month for 2024.

Casting our eyes back a century to February 1, 1924, we see both how much daily life in the nation’s capital was suffused with the Jim Crow Era thought and social structures of the times, while we also catch glimpses of pride in the impressive achievements of African-Americans in Washington, D.C. during an era of great post-war promise – The Jazz Age and The Roaring Twenties.

Not surprisingly, the top story in Washington’s Evening Star newspaper on February 1, 2024 splashed news of former President Woodrow Wilson’s impending death. “Wilson Near Death Following Relapse. End Expected Hourly. Digestive Disorders Take Sudden Turn for Worse. War President ‘Ready’ to Die. ‘I’m a Broken Machine,’ Former Executive Tells Dr. Grayson. Wife at Bedside, Daughters Called. Message of Sympathy Comes From Coolidges Among First.”

For Washington, D.C. however, Wilson’s death was the end of a complicated racial legacy. While the 28th president was an essential leader in shepherding the United States through the First World War and establishing post-war order in Europe and the world, he also changed the tenor of race relations in the nation’s capital. His predecessor, Theodore Roosevelt, a Republican from the “Party of LIncoln,” had desegregated the federal government, while Wilson, a southern Democrat, ordered the federal government re-segregated in 1913.

A glance through that day’s Evening Star quickly brings the segregationist and racialized (or racist) thought of the day to the fore. Notably, several examples involve racism toward non-White peoples who were not African-American.

“Two Eskimos Hang Today For Slayings,” an AP story from Edmonton, Alberta begins on page 2. “…Ali Omiak and Tetamanma, go to the gallows today at the royal Canadian mounted police barracks at Herschel Island to pay the penalty for the slaying of Corry Dock of the mounted police…. The tragedy, which resulted in the death of the two white men, as well as several Eskimos, grew out of a feud which began when Binder fell in love with a native girl…”

Another – “Indian Dies During Fight for Freedom” – on page 12, concerns a Native-American man denied admission to a Maryland state clinic for tuberculosis patients because a judge ruled him ineligible owing to a “vagrancy” violation on his record. Of course, “vagrancy” laws were a central component of the Jim Crow era, allowing law enforcement to essentially arrest a person of color for simply “being in the wrong place at the wrong time.”

While the story has a touch of sympathy for the individual involved, it’s cast in strictly racial terms with which readers of the time were familiar. It begins: “The strict letter of the law triumphed over humanitarianism Wednesday when Jesus Mendoza, a full-blooded Cherokee Indian, died of tuberculosis in the house of correction… The red man believed he was friendless, but before his end came, club-women, medical men, a circuit judge, officials at the house of correction and the state board of health were interested in this case… [Mendoza’s] arrest and subsequent court proceedings caused the helpless red man to lose accommodations assigned him at the overcrowded state sanatorium. The state health department gave orders that he be returned to his cabin under the care of a nurse, but Mendoza died while the attempt was being made to defeat the law’s red tape.”

A glimmer of hope and pride in Black History does appear, however, deep in the 40-page Evening Star of one-hundred years ago. “Dunbar Student Gets Essay Prize,” the headline reads. “Dorothy Maude Houston Winner in The Star’s Competitive Test Writes of Lenin’s Death. Check for $10 Sent as Author’s Award. Teachers Elated Over Her Success.”

In this story from the editorial staff of The Evening Star, a sense of pride in Black achievement shines through. “Dorothy Maude Houston, a student at Dunbar High School, writing on the death of Nicolai Lenin, premier of soviet [sic] Russia, won the third prize for the first contest week in The Star’s ‘best news story’ contest, it was announced today by the committee of judges composed of editors of The Star. A check for $10 has been sent to Miss Houston with the compliments of the managing editor of The Star. Miss Houston is fifteen years old and lives at 1758 T street northwest. She is the daughter of G. David Houston, head of the department of business practice of Dunbar, and has an unusually good scholarship record, according to officials of the institution…”

Published in full by The Star, Houston began her essay, “Because I am interested in history, the article ‘Nicolai Lenin Dies Following Stroke at Moscow Villa,’ in the first column on the first page of The Star for Tuesday, January 22 appeals to me,” Her critique of the piece is strikingly adept for a 15-year-old student. “The article is well developed, and gives a great deal of information in a comparatively short space,” Houston writes. “Out of the simple fact that Lenin has died, the story develops to give a comprehensive insight into the man’s life, character and activities. Even his personal appearance is definitely impressed upon you. You clearly see the studious boy, interested chiefly in the conditions of his fellow countrymen; then the man, still deeply interested in social conditions and political history; and finally the man following out his revolutionary and socialistic impulses and seizing the reins of government.”

Intrigued by who this bright student, Dorothy Maude Houston, was, I researched her name and found her essay awarding by The Evening Star listed in a marvelous compendium of Black History by the title “The Negro Yearbook: The Negro in 1922-1924.”

“Miss Dorothy Maud [sic] Houston, student in Dunbar High School in Washington, D.C. was awarded third prize in a short story contest conducted by the Washington Star for school children,” the listing read. While I could find no more on Houston, this source itself is a marvelous prize in preserving the Black History of the times.

Scanning over the “Year Book” for those years, one quickly appreciates how conscientiously its editors recorded Black achievement – especially in the context of a segregated society – not only in Washington, D.C. but throughout the nation.

“Miss Colleen Minor Brooks, Dunbar High School, Washington, in an open contest of school children of all races and groups of that city conducted by the Women’s American Legion for the best essay on the subject, ‘A Character in American History that Illustrates the Highest Ideals of Citizenship’ was awarded a prize of $20 in gold offered by this Women’s Organization….”

“Audrey Farrar won third prize in a contest among high school students, white and colored, Fort Smith, Arkansas, for a composition on “Fire Prevention.”

“John T. Risher Awarded Prize $1000 for Best Plan Keeping Navy Records.”

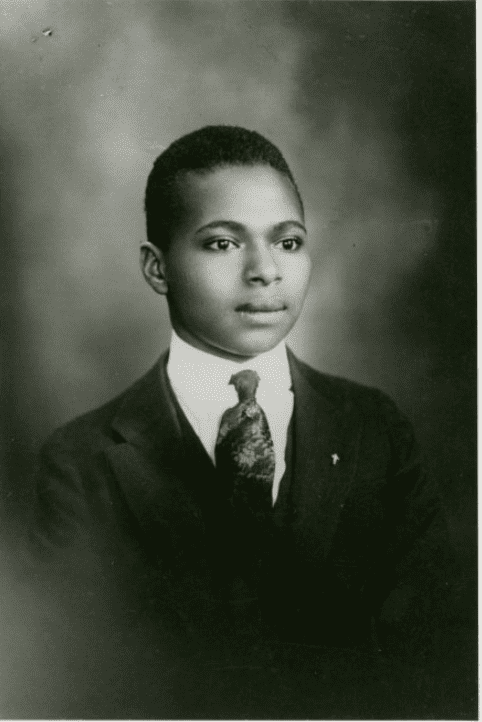

“Countee P. Cullen Wins Second Prize in Poetry Contest.” Wait, is that The Countee Cullen, famous poet of The Harlem Renaissance in the 1920s? Yes indeed! The blurb on Cullen’s second-place poetry prize begins: “Countee P. Cullen, graduated in 1923 as valedictorian from Dewitt Clinton High School, New York City, with an average of 93 per cent for the whole four years of his high school course. He won the Douglass Fairbanks oratorical contest with his original poem, “I have a Rendezvous with Life.”

Countee P. Cullen. NYPL Digital Collection.

“Negro Students Elected to Membership Phi Beta Kappa.”

“Charles W. White Awarded Harvard University LL.B. Degree Magna Cum Laude.”

“Negro Physician Reported to Have Made Serum for Goiter Cure.”

“Who’s Who In America” 81 Negroes Listed in 19-24-1925 Edition.” One recognizable name in this listing: “W.E.B. Du Bois, Editor.”

Perhaps most striking in this compendium, however, are stories that would strike one today as over-the-top caricatures on race – as highly offensive as one might imagine. Any real look at Black History one-hundred years ago, also requires an understanding of the demeaning social and political environment dedicated and high-achieving students like Dorothy Maude Houston had to face each day.

One such article: “Black Mammy Monument. Daughters [of the] Confederacy Sponsor. Negroes Raise Strenuous Objection.” It begins, “At the suggestion of Senator John Sharp Williams of Mississippi a resolution passed the United States Senate in 1923 to erect at the Capital of the nation a monument to the black mammies of the South. Thousands of men and women who look back with affection and appreciation to their black mammies were behind the movement to erect this monument. Thousands of others, including the majority of Negroes, were opposed to the erection of such a monument and suggested that instead, something be done for black mammy’s children…”

Another is headlined, “Negroes Object to Term ‘Pickaninny Freeze.’” It begins, “As a result of an amendment to Chicago’s moving picture ordinance introduced by Alderman R.R. Jackson, and passed by the City Council in 1922, no permits in the future are to be issued for the exposition of pictures which tend to hold up to scorn certain races.

“Section 1627. Immoral pictures – permit not granted. If a picture or series of pictures for the showing or exhibition of which an application for the permit is made, is immoral or obscene, or holds up to scorn or ridicule any nation or the people thereof, or portrays any riotous, disorderly or other unlawful scene, or has a tendency to disturb the public peace, or contain terms, titles, phrases such as “kike,” “dago,” nigger,” “wench” “turk,” “coon,” “shine,” “mick,” “darky,” etc. which reflect opprobrium or ridicule on a race, nation, religious sect, denomination or constituted authority of the law, it shall be the duty of the General Superintendent of Police to refuse such permit.”

“Negroes object to the term ‘Pickanniny Freeze,’ as a designation for an ice cream similar to the ‘Eskimo Pie.’ the article concludes.

One century out, we’ve come a long way – but still have so far to go…