At Home: Spotlight on Home Illumination

By • July 8, 2024 0 1127

During the last several years, many of us have completely redesigned our work arrangements so we are in our homes for longer periods and so, we have the chance to observe the seemingly simple items in our homes in new ways. If we take the time to look closely, we can learn some interesting new things about our homes and the elements therein and about how people lived in earlier days.

In early American homes, the setting sun shrouded the typical home in darkness. For the ordinary 17th-century American, bright lighting simply was not worth the relatively high cost of a candle and so, most lived by the light of the hearth and postponed many tasks requiring more light until the sun rose once again.

Just try to imagine life before electricity, aptly described by an 18th-century writer who described a grand ballroom that was lit by amassed candles and was “as bright as day.” In actuality, he may well have been talking about a room equivalent to one lit by a 25-watt bulb today.

In the earliest years of America, electric lighting was preceded by candles, which provided the best sort of illumination available at the time. However, due to the candle tax of 1706, which also forbade the making of homemade candles, wax candles became too expensive for most colonial households. So, the colonists often used oil lamps to supplement firelight and costly candles.

The simplest kind of oil lamps was the Crusie, consisting of a circular iron pan with one side shaped into a channel which would receive a wick and burn grease or oil. After that came the so-called improvement – the Betty lamp – which replaced the upper lamp pan with a metal wick holder inside the lower pan and added an oil cover. Both of these were smelly, smoky, and dangerous.

CB2 light.

These were followed by gas lamps, which were able to produce a brighter light and were an immense improvement, quickly spreading gas-powered lighting throughout American society during the 1800s. Although at first, primarily used in city streetlights, by the 1840s, gas lighting began to make a tentative appearance in the city home.

Gas provided quite a stunning improvement to people’s ability to read, write or sew in the evenings with minimal effort, but it, nevertheless, had drawbacks. In addition frequent explosions, it replaced the oxygen in the air with black and noxious deposits. That Victorian ladies frequently fainted may have been due, in part, to tight-lacing, but was also because of a lack of oxygen in their gas-lit drawing rooms.

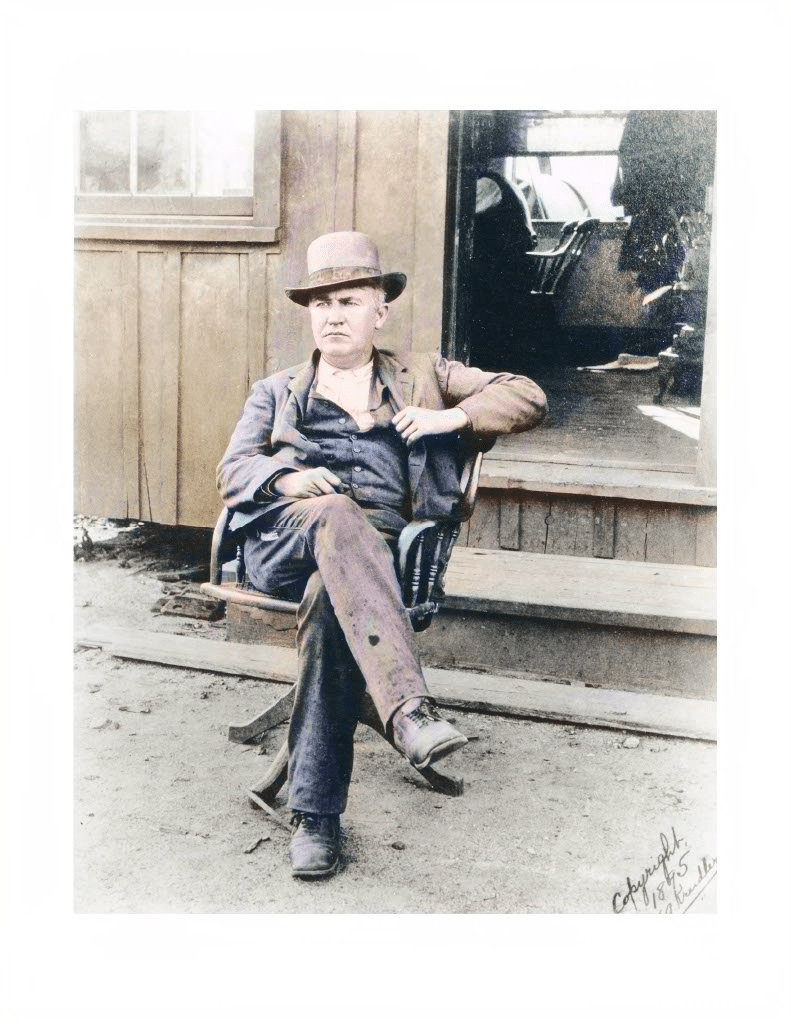

Just as people warmed up to the idea of lighting with gas, Thomas Edison arrived on the scene with plans to make electric lighting available to the masses by patenting the first commercially successful bulb in 1879. Even though he did not actually invent the original light bulb, he sensed that it could become a revolutionary product and improved the bulb’s technology to make it useable in the everyday American’s home.

Although some 19th century homes had chandeliers, bracket lights, and other fixtures like those we use today, many homes and stores up through the 1920s used pendant lights. These consisted of an exposed bulb in a keyed socket that hung on twisted cotton insulated cord from a ceiling rosette. The house wiring, whether exposed on the ceiling or concealed in the attic, connected to screws on the rosette where the drop cord connected through the rosette to the house wiring. Generally, there was no wall switch in these installations; one walked to the center of the room and twisted the socket key.

The journey to harnessing and distributing electricity wasn’t easy or quick. One of the earliest challenges involved the generation of the power itself; an early milestone was achieved at Niagara Falls, New York. The first large-scale, power-generating operation was established, supplying electricity to nearby Buffalo and marking a groundbreaking achievement in long-distance energy transmission.

And, as with many new and expensive technologies, electricity was first used in businesses, where it could increase profits rather than comfort. It cut down on maintenance and risk of fire in factories, mills, and other places not hospitable to gas lighting. However, since the cost of electricity transmission was exorbitant, it rendered electricity inaccessible to many rural areas well into the 20th century; there were farms in America still operating without electricity as late as the 1930s. Conversely, wealthy urban homeowners adopted the technology sooner, even though a light bulb cost the same as the average week’s wages and one needed their own generator. Different towns had different currents until the National Grid was developed in 1938.

In those early days of home electrification, electricity was transmitted inside the home by bare copper wires, with no insulation. Sockets, switches, and fuse blocks were wooden and there were no voltage regulators, so lights would brighten and dim, based upon demand. In the earliest set-up, hot wires and neutral wires were run separately and were insulated using cloth, which degraded over time. Also, wires were not grounded so the risk of danger was high. From the 1920s to the 1940s, flexible armored cable, which offered some protection from wire damage, became commonplace and in the 1940s, several insulated wires were enclosed in rigid metal conduit tubes.

Today, electric lighting accounts for around 15% of an average home’s electricity use. LED technology, a type of solid-state lighting — semiconductors that convert electricity into light — is the energy-efficient trend for the modern home. LED bulbs use up to 90% less energy and last up to 25 times longer than traditional incandescent bulbs, plus they save the average American home about $225 in energy costs per year.

Another electric upgrade is the smart residential lighting system, which is becoming mainstream, enabling homeowners to control ambiance, color, and intensity through smartphones or voice commands. Modular and customizable fixtures empower users to tailor lighting solutions to their personal preferences, reflecting a dynamic shift towards personalized, technologically sophisticated, and eco-friendly residential lighting. A far cry from candles and oil lamps.

According to the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions, renewable energy power sources – wind, solar, geothermal, hydroelectrical and nuclear are the fastest-growing sources of electrical power in the US. Wind and solar power are breaking records, and renewables are expected to become the world’s largest sources of electrical energy by 2025. Eco-conscious entrepreneurs are creating technologies for auto manufacturing, heating, cooling, cooking, and some manufacturing to go electric. As climate change is registering rising temperatures, which in some places are not compatible with human life, a transition to renewable power sources as our primary producers of electricity is, hopefully, likely.

Michelle Galler is an antiques dealer, columinist and painter residing in both Maryland and Virginia.