JFK We Knew Him Here

By • May 24, 2017 0 852

When Democrat John Fitzgerald Kennedy became President of the United States — by the thinnest of margins — I was a few months removed from high school graduation and weeks from my 22nd birthday when he was assassinated in Dallas.

With a national and a local flourish, we are now about to celebrate the 100th birthday of John F. Kennedy, on May 29, which (providentially) also happens to be Memorial Day, the day on which we remember those Americans who died in the service of their country.

The forward-seeking national spirit he inspired will be widely recalled and honored. A major celebration will take place on his birthday at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, which serves as a memorial to the man and to his insistence that excellence in the arts is among the highest achievements to which a country and a people can aspire.

Millions have died since his inauguration and millions have been born. John F. Kennedy lives on. He not only endures, but continues to inspire. His shocking death ended his life, but not the life he persists in owning.

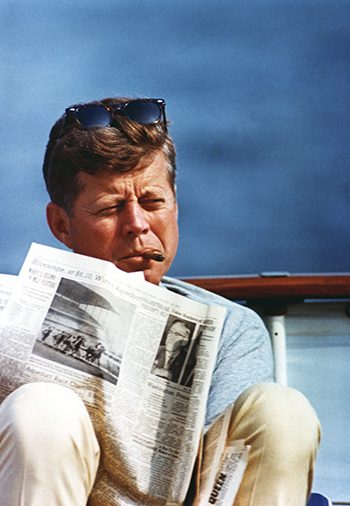

He is not the same man who was part of a large Irish family that transformed this country with its life and blood, not the scholar, the voracious reader, the author, the war hero, the wit, the risk taker, the inspiration of millions and of memory. He is something other than himself, in addition to himself and larger than himself, but very much alive.

His life, his biography, his speeches and the images that remain as tokens, the words upon words written about him, the judgments made, will be unspooled and examined all over Washington — in think tanks and museums, at the Kennedy Center, in song and tome, in speeches and anecdotes. It will not be as if he had lived only for a time, or that his life stopped in that singular, violent moment, but as if the life he lived has become a permanent time machine that continues to have the power to inspire, to embrace the future, to show strength informed by tragedy, compassion, imagination and humor.

He was the product of immigrants, millions of them, often despised on their arrival from Ireland.

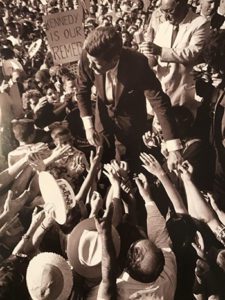

Georgetown is always a place haunted by his most accessible, lively aspect: the young politician, the young husband and father with the astonishingly unforgettable Jackie as his wife. At this newspaper, we have evoked the spirit and imagery often and with regularity — Jack in a T-shirt so white it would make mothers proud, Jackie tousled and energized. Georgetown is full of JFK touchstones and homes, streets he walked, restless on inauguration night. All of us somehow feel we knew him here, heard a broad Boston Irish accent in passing, just out of reach.

He and that Irish clan — noisy, boisterous, tight, at once Catholic and catholic — had a story already fully formed by the time he became president. In that brief time (less than three years), JFK became in action and in thought and rhetoric what we instinctively wanted in an American president. He became a leader, a quality in him that seemed both natural and hard-won.

He used words as if they had meaning beyond the breath it took speaking them; he was educated and intelligent without that creating a distance between him and us; he had self-evident physical courage; he had a sharp wit, informed by loss and tragedy. He came into office, if not fully formed, full of a life’s experience of loss, heroism, speechifying, achievement, knowledge of the world. He was no rookie.

He did not make promises. Instead, he exhorted us to ask ourselves “what you can do for your country.” He asked us to look beyond our borders and into the divisions of race, with which even he had little experience. He asked us to breathe freely and make it possible for others to do so. His phonetically mangled but historically stirring “Ich bin ein Berliner” came from somewhere deeper than a dictionary.

Memory has its way with heroes and presidents. After his death, secrets — shameful ones, exposing deep flaws and recklessness — emerged and seemed for a time to taint his memory. And then they didn’t. Rather, they became part of the man, the prince’s livery, no more, no less. He was a man who had, it’s fair to say, kept the missiles of October from flying. He was a man who insisted that music and art were every bit as important as armaments (even if it’s likely that he preferred an Irish jig to Mozart). He was and remains the man who insisted we imagine the future, who asked us to look up and sent us on a mission to the moon.

That bust in the Kennedy Center foyer speaks of him, gives him silent voice and contains inside it room for all of us.

The poet Charles Wright wrote: “We’re not here a lot longer than we are here, for sure.”

Yet, here we are, and more important, here he is, as if all that happened restored and retained him, giving him a life forward, prodded by our imagination and memory, into our future.