Last Chance: Gordon Parks at the National Gallery

By • February 5, 2019 0 2666

For now, the federal government has reopened, and with it have the doors to the Smithsonian museums and the National Gallery of Art. The shutdown-induced closures of D.C.’s major museums accentuated a familiar regional idiosyncrasy: the federal funding that seeps into this city’s every pore gives it an odd cultural complexion.

It is unusual in this era to have so much government sponsorship of art-related ventures in one place. As I recently argued, while the temporary closure of these museums won’t cause any lasting damage, it underscores our government’s fundamental and self-destructive undervaluation of creative enterprise as a conduit to the nation’s entrepreneurial spirit.

In order to survive, governments need to keep up with the constantly shifting landscape of culture itself. Art propels the development of culture. Greater support of artistic activity could move our government to the front lines of cultural development, instead of lumbering behind it with the speed and temperament of a cartoon scrooge.

By contrast, and in a somewhat prophetic display of narrative juxtaposition, the exhibition “Gordon Parks: The New Tide, Early Works 1940-1950,” on view through Feb. 18 at the National Gallery, offers direct vantage into an era when the American government sponsored art projects on a national scale for both cultural and industrial advancement. The result, it seems, was not only good for national industry and morale, but launched the careers of new and unlikely voices who would go on to have an outsized impact on our cultural dialogue.

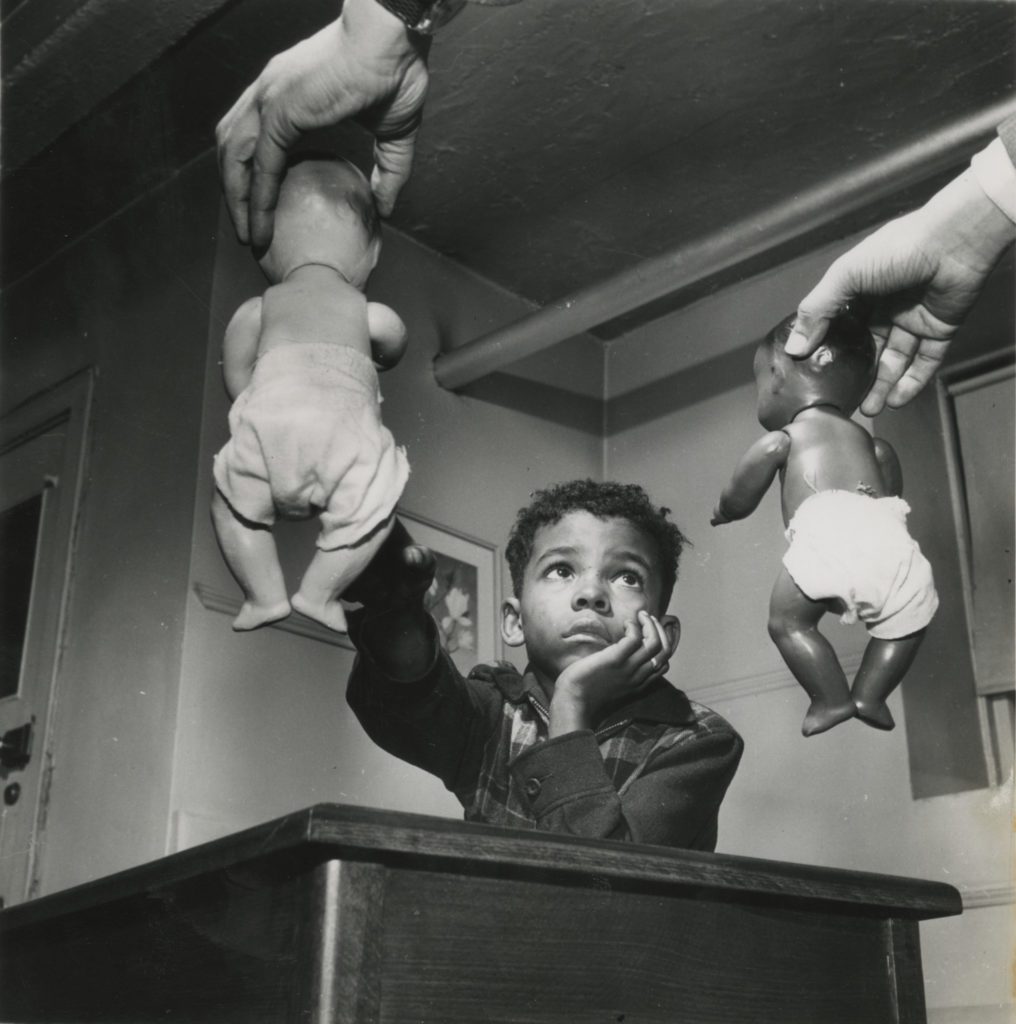

The show explores the lesser-known yet incredibly formative decade when Parks (1912-2006) grew from a self-taught portrait photographer and photojournalist to the first African American photographer at Life magazine in 1949. Providing a detailed look at his early evolution through some 150 photographs, as well as magazines, newspapers, pamphlets and books, the show focuses on how Parks influenced and drew inspiration from a network of contemporaries, notably Charles White, Roy Stryker, Langston Hughes, Richard Wright and Ralph Ellison.

The exhibition is also organized by the major projects he was assigned and commissions he was awarded, which allowed the ambitious, burgeoning young Parks to develop his photographic style while traveling the world and supporting a family.

It is not trivial that two of these early contracts were awarded by now-defunct government agencies: the Farm Security Administration and the Office of War Information.

The first section of the exhibition, A Choice of Weapons (1940-1942), opens with some elegant society portraits that established Parks as a professional photographer in Saint Paul and Minneapolis. After moving to Chicago in early 1941, he was given access to a studio in the South Side Community Art Center, the epicenter of Chicago’s African American art scene, established with support from the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project (another now-defunct government agency).

There he developed relationships with other artists, notably the painter Charles White (1918-1979), whose profound retrospective last year at New York’s Museum of Modern Art finally cemented his status as an icon of American art. White, whose work engaged deeply with political and civil activism, encouraged Parks to take his camera onto the streets to document the surrounding South Side neighborhood.

Thus inspired, Parks applied for and won a fellowship from the Julius Rosenwald Fund to spend a year “portraying the Negro in his intellectual, professional, educational, social, farm, and urban life.” This offered him the opportunity to work with legendary economist and photographer Roy Emerson Stryker at the equally legendary Historical Section of the Farm Security Administration.

The second section, featuring photographs created during his time with the FSA, is titled Government Work (1942) — a title that I don’t imagine will be lost on Washingtonians.

While Parks made promotional pictures of federal efforts to improve conditions for African Americans, he also documented the continuing effects of racism in D.C. In July of 1942, he photographed Ella Watson, a government cleaning woman. His now iconic portrait, “Washington, D.C. Government charwoman,” reveals her dignity and dissolution, as she stands stoic with mop and broom in front of an American flag. Watson and her family actually became the subject of an extended series in which Parks chronicled their lives at home, at work and in their community. Through projects like this, Parks fused his skills as a portrait photographer with the principles of photojournalism.

The exhibition moves through his projects for the Office of War Information later that year, creating photographic series on tenement housing, food production, the first fighter group of African American pilots and the children of Harlem.

The remaining galleries focus on his work for the Standard Oil Company, his first jobs with major fashion and lifestyle magazines (including Glamour and Ebony) and his first assignments for Life. Throughout these galleries, his photography blossoms into the sort of mastery one expects to see of a photographer of Parks’s renown.

But I visited this exhibition less than a week after the National Gallery’s reopening from the longest government shutdown in U.S. history.

Putting aside their substantial financial losses, in the two weeks since the government has reopened, the Smithsonian and the National Gallery have been deluged with visitors. (According to colleagues, the Library of Congress and the National Archives, too, are busier than they have ever seen.)

It was mesmerizing, if bittersweet, to see upon the walls of the National Gallery of Art the great history and breadth of government arts funding, which has been steadily chipped away since the end of World War II. Through the lens of Gordon Parks, it comes into focus that our country has a remarkable artistic heritage that coincides with social justice. At one point, our government was a part of this movement. Perhaps one day — though clearly not anytime soon — it will be again.