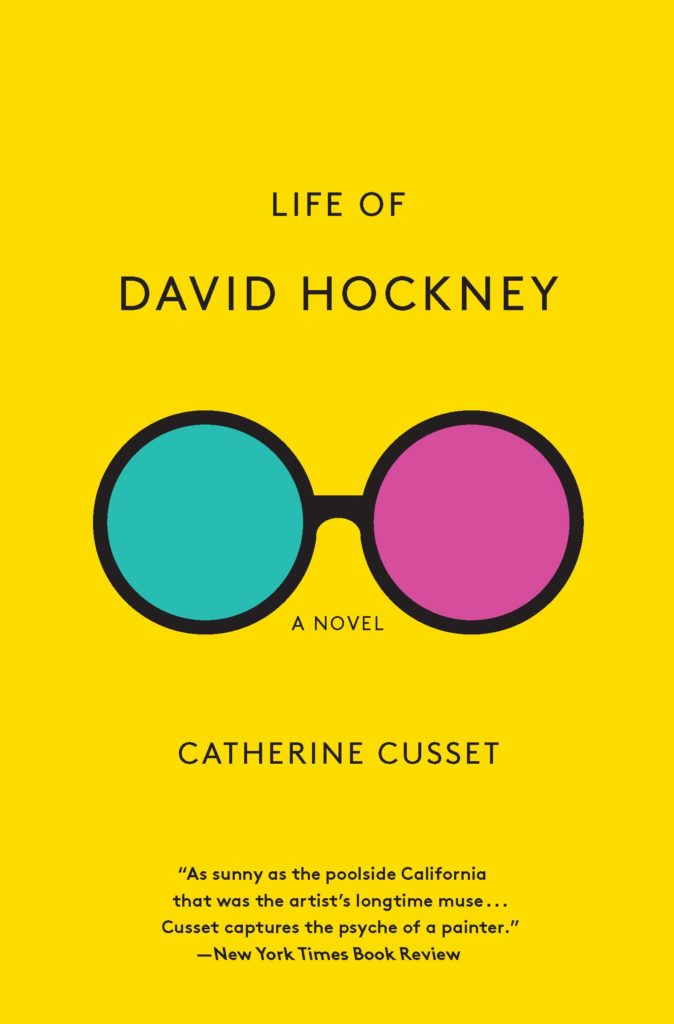

‘Life of David Hockney: A Novel’

By • September 11, 2019 0 1120

THIS MELODRAMATIC, FICTIONALIZED BIOGRAPHY DREW PRAISE FROM ITS REAL-LIFE SUBJECT

People who know art will recognize the name of David Hockney, and those who like the artist will enjoy this romp of a book, which purports to be “a novel and a biography,” a hybrid of sorts that cross-fertilizes fact with fiction.

Brief and breezy at under 200 pages, “Life of David Hockney” by Catherine Cusset reads like a fanzine about the man considered to be England’s most famous living artist.

At the age of 35, Hockney made auction history in 1972 when his “Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures)” sold for $90 million. He held that record for 47 years, until Jeff Koons’s “Rabbit” sold for $91 million.

Cusset wrote this book as a love letter, saying as much during an interview on NPR: “I hope he will consider it an homage.” She admitted she “was very scared” about his reaction. “The man … is very rich and he’s super-well-known. And he cares about his image. And he can hire very good lawyers.”

She needn’t have worried. Hockney has flicked off major art critics like Hilton Kramer and Clement Greenberg for disparaging his work as “superficial” — too pleasant to be taken seriously; then he’s laughed all the way to the bank. Upon publication of Cusset’s book, Hockney was gracious: “[It] caught a lot of me. I could recognize myself.”

The author had not known anything about the artist until she looked at his work on the internet. Then, “I really liked him … I loved his incredible freedom at every level… always following his desire, his impulse, being true to himself.”

The author of 13 novels about “things that are connected to my life — my mother, my mother-in-law [and] sex,” Cusset holds two doctorates — one from Paris Diderot University, where she wrote a dissertation on the Marquis de Sade, and one from Yale, where she wrote on the 18th-century libertine novel. So she’s well-schooled on the subject of sex and the pain and pleasures of the flesh.

As a gay man, Hockney celebrates homosexuality in much of his art (“We Two Boys Together Clinging,” “Doll Boy,” “Adhesiveness”). With staccato sentences, Cusset dives into his personal life like a devotee of True Romance potboilers. She reports on his nude revels — filled with poppers, cocaine, and Quaaludes — the fraught years of AIDS and the sad deaths of many friends.

She tracks his torrid five-year affair with Peter, who becomes his model and muse. (Most of the men mentioned in the book, including friends, lovers and assistants, are identified by first names only.)

Then — cue the drums — comes the traumatic breakup with Peter, when he leaves the artist for a younger man. In sob-sister style, Cusset writes how Hockney “was stricken with depression” and kept asking himself, “How could he get Peter out of his blood?”

Even three years later, “He would still cry when he thought of Peter.” This leads to second-guessing their relationship: “Had Peter ever had any real feelings for him?” “Where was the boy whom he had loved so passionately?” “Would the pain ever go away?” “Weren’t three years enough?”

Cue the violins.

For those unfamiliar with Hockney’s art, this book will disappoint, as it contains no reproductions or illustrations. Cusset cites several works by name but describes few, probably figuring that fans will have read at least one of the artist’s 27 books and be able to recall images such as “A Bigger Grand Canyon,” “My House, Montcalm Avenue, Los Angeles” and “Model with Unfinished Self Portrait.”

Still, to write about David Hockney without showing his paintings is like writing about Winston Churchill without quoting his speeches.

In discussing Hockney’s art, Cusset notes that the color blue suffuses many of his paintings, from the aqua swimming pools that first made him famous to his “Self Portrait with Blue Guitar,” inspired by the Wallace Stevens poem “The Man with the Blue Guitar.”

This poem spoke to Hockney, who saw himself as a man who can’t play things as they are, but through his talent — his blue guitar — he summons the power to recreate the world from his imagination. The guitar is the artist’s talisman and can only be strummed by the gifted.

“Life of David Hockney” begins with a young, happy-go-lucky man who moves from the north of England to Los Angeles to pursue his passion for painting and music and beautiful boys. He bleaches his hair blond, wears red polka dots with purple stripes and, with a flair for friendship, surrounds himself with an adoring coterie that accompanies his rocket to success.

He achieves great wealth and global recognition. He travels the world, collecting all its tributes, and seems surely headed for happily-ever-after. But age and disability intrude, leaving the last image of David Hockney as a deaf 82-year-old man, sitting alone on his porch, smoking a joint that he buys with a medical marijuana license “to calm his anxiety.”

Fugit irreparabile tempus.

Georgetown resident Kitty Kelley has written several number-one New York Times best-sellers, including “The Family: The Real Story Behind the Bush Dynasty.” Her most recent books include “Capturing Camelot: Stanley Tretick’s Iconic Images of the Kennedys” and “Let Freedom Ring: Stanley Tretick’s Iconic Images of the March on Washington.”