Fall Arts Preview: The Reach – The Kennedy Center’s Expansion

By • September 11, 2019 0 926

When Deborah Rutter took up the reins as the new president of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, things sounded a little chaotic in the middle of her first official day of work. “My office looks terrible,” she said then, during a telephone interview in September of 2014. “There’s boxes and stuff all over the place.”

The good news? “We had a staff meeting to meet everyone, which was absolutely great.” And, she confided, “actually, the most important part of the day was, of course, deciding what my daughter would wear to school.”

Five years later, on a recent Tuesday, things were no less fraught, although for a different reason. Her office in the Kennedy Center seemed shipshape: big conference table in the center, family pictures behind her desk, artwork on the wall and daughter Gillian already off to Duke.

But the atmosphere of big changes underway still pervaded the room. It was, after all, only a few days until the official opening, on Saturday, Sept. 7, of the Reach, the 48-year-old Kennedy Center’s first major physical expansion, to the tune (at last count) of $250 million.

The opening of the Reach, a set of dramatic pavilions and plazas, is being celebrated with a two-week super festival, running through Sunday, Sept. 22, that kicked off with an ambitious parade, dubbed “The Future Is Now and I Am It: A Parade to Mark the Moment.” Over the festival’s 16 days, there will be some 500 performances on the new campus.

Officially, Rutter has said that the Reach Opening Festival “celebrates our nation’s incomparable diversity. Inviting full participation, immersion and discovery, it’s the perfect way for people to experience what the Reach has to offer.”

As an expression of Rutter’s personal and professional history, her approach to and feelings for the performing arts and her continued ambitions for the Kennedy Center, that’s pretty succinct.

Kennedy Center President Deborah Rutter at the Reach, the performing arts center’s first expansion since its opening in 1971. Photo by Todd Rosenberg.

A WAY OF THINKING ABOUT THE ARTS

While she isn’t the originator of the Reach — the decision to do a major expansion had already been made before she arrived — Rutter is, and has been all along, the personification, the best interpreter and shaper, of not only the Reach, but the Kennedy

Center as a whole.

“It’s about the future. It’s a way of thinking about the arts, and about the spaces it occupies,” she says. “It’s definitely about the word itself. And when you think about it, it’s not just about the word ‘reach’ as in reaching out. Sure it is, but more of things set in motion, reaching out, reaching in, bringing in.”

The Reach is unique because it brings the community to the art, not just in quiet appreciation, but with interaction, intimacy, closeness, in a setting that’s very active and interactive. It appears to be neither a mere extension of the Kennedy Center nor, perhaps least of all, separate, but rather an organic entity that connects to the Kennedy Center directly. Kennedy’s words are here, too.

“In terms of the arts, and performing arts especially, he was above all inspirational, and he understood the critical importance of the arts in the life of a nation,” Rutter says of the center’s namesake.

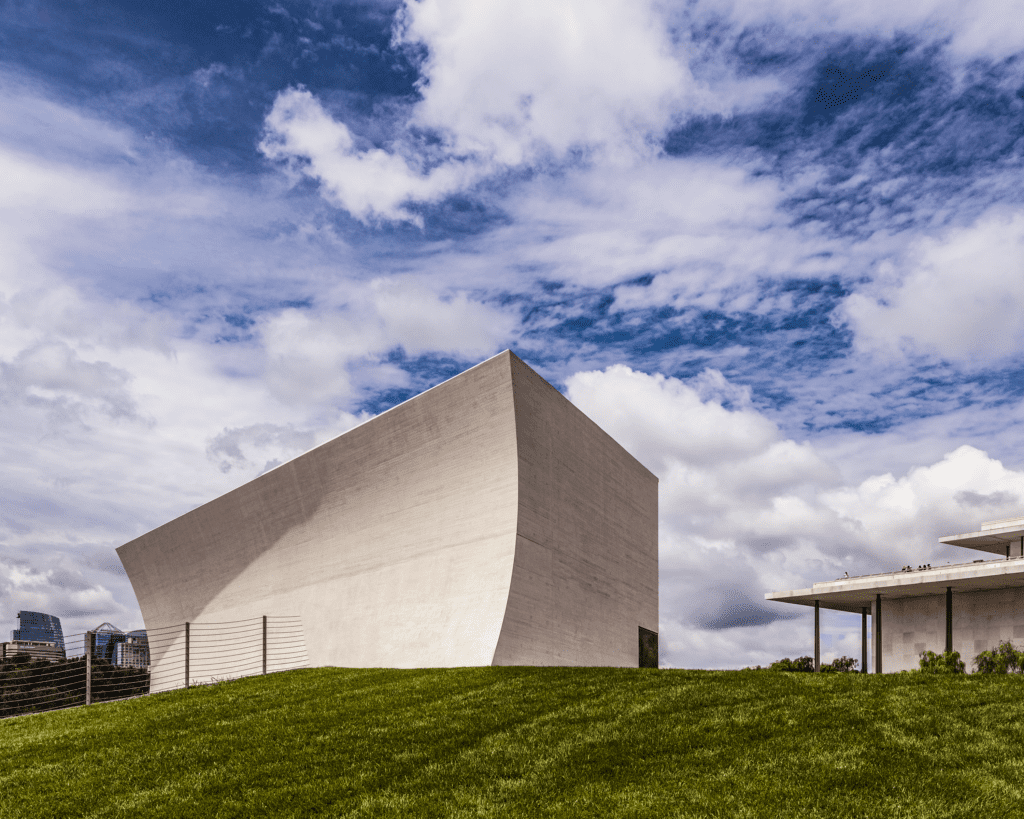

You can feel what the Reach expresses just by looking at it in quiet contemplation. The work of architect Steven Holl, it’s a soft, not aggressive, but spare and sharp thing of architectural beauty. Its pavilions are whalebone white, with a clean look and a path to the Kennedy Center. A good part of it is underground, covered by a grassy, garden-like open space.

It includes visible artwork outside and in, by Joel Shapiro, Roy Lichtenstein, Deborah Butterfield and Sam Gilliam (one of his splashy drapes). Also visible outside are a pedestrian bridge, upper and lower lawns, a video wall, the Reach Plaza — which connects to the Kennedy Center — a reflecting pool and the presidential grove of ginkgo trees, plus an Arlington oak.

On Level A, visitors will find a welcome lobby, a flexible space for meetings called PT 109, the Moonshot Studio (a dedicated interactive arts learning space), the Skylight Pavilion and the Justice Forum, which includes a performance space with fixed seats, also referencing JFK’s five ideals of freedom, courage, justice, service and gratitude.

The below-ground levels also feature studios (named J, F and K), lecture halls and rehearsal spaces for theater and dance and other performing arts, as well as classrooms and lounges for the public and students. It features acoustical plastic ceilings and large frosted glass walls with etched quotes from President Kennedy. There is also a River Pavilion and Mezzanine, which can be used to rest, for meetings or as an artist’s lounge.

WELCOMING NEW GENRES AND NEW AUDIENCES

The list of performers and activities for the festival are reflections of Rutter’s approach to what cultural and performing arts centers do — reach out to new forms, welcome new genres and new audiences and bring it all together. On the lineup, you’ll find the names of such ensembles and performers as the Heritage Signature Chorale, the 300-voice, D.C.-based community chorus; Rock and Roll Hall of Famer Bootsy Collins; Kennedy Center Artistic Director for Jazz Jason Moran; playwrights Aaron Posner and Karen Zacarias; the Broadway Collective; and jazz bassist Esperanza Spalding. Among the special events will be a Hip Hop Block Party on Sept. 14 and, the following day, hosted by picture-book author Mo Willems (the center’s education artist-in-residence), Mo-a-Palooza Live!

Running through the festival like a live and cursive river is a theme: art is by and for everyone, from presidents to cultural leaders to me and you.

In her earlier leadership positions — executive director of the Seattle Symphony, then president of the major-league Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association — Rutter’s approach was expansive and inclusive in the arena of community engagement.

“When you deal with institutions that are supposed to have one identity — an orchestra, a theater company, a dance company — it’s difficult sometimes to get beyond that identity,” she says. “Even with the Kennedy Center, people sometimes see this gigantic institution, with its white bulwark, housing a number of different groups, from the opera to jazz to children’s theater and so on. It’s still this one identity.”

In terms of the ongoing debates about genres and changes in classical music and opera and how they are presented, Rutter has done a lot to make sure that the Kennedy Center has expanded and reached out, even without the Reach.

“It’s about the community, about realizing that there are all sorts of sounds and music, and new playwrights and musical forms,” she says. “To me, the Reach is about looking at performance spaces in a new way. You can come to the Reach just for the sake of it, or use it as a welcoming and active gateway or a kind of eye-opener to come closer and closer to the art and artist, being close, sitting in, watching the process and being a part of it.

“I don’t see the Reach as separate spaces from the Kennedy Center. It’s a living part of it. Its fresh air, fresh people,” she says.

“To me, it’s the future of what the performing arts can do, and how you experience them. The Reach is bound to leave its imprint on the people who come there, sit there, listen, take part, learn, see and hear new things from a different vantage point, watch or listen to the river go by and then partake of the center’s choices.”