Jasper Johns at the Whitney

By • December 8, 2021 0 3585

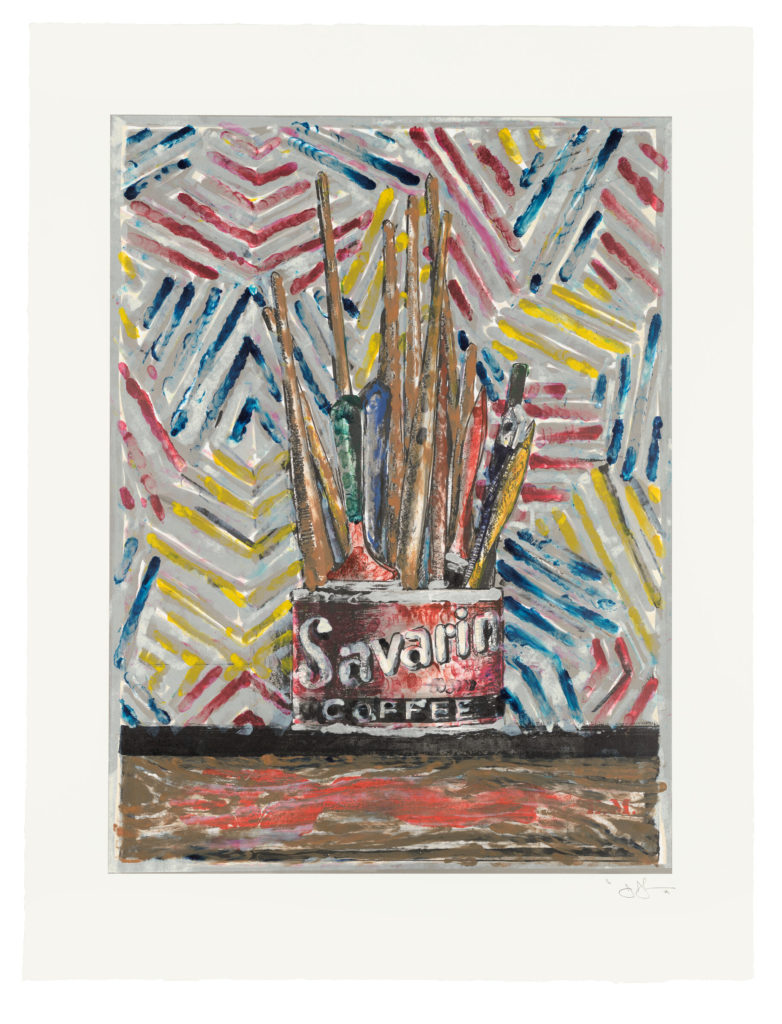

Savarin by Jasper Johns, 1982. Photo courtesy Whitney.org.

Thanks to Andy Warhol, Campbell’s soup and Brillo pads hold an honored place in art history. Two years younger, Jasper Johns got there first with Ballantine ale and Savarin coffee, pointing the way to Pop Art as he had to Conceptual Art and Minimalism.

Like holy relics, Johns’s painted bronze casts of Ballantine and Savarin cans are centerpieces of the New York half of “Jasper Johns: Mind/Mirror,” on view through Feb. 13 at the Whitney Museum of American Art. (The retrospective’s other half is at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.)

Dating to 1960, these sculptures of a not-quite-identical pair of ale cans and a coffee tin crammed with paintbrushes shook the art scene the way Johns’s ironing-board-flat American flag paintings, on the walls of the Castelli Gallery, shook it in 1958. Wasn’t contemporary art supposed to be abstract yet expressive, the paint slathered over, poured onto or soaked into the canvas? Were the flags patriotic or anti-American? Were the cans some kind of a joke?

Johns’s revelation, it is said, came in 1954, when he dreamed of painting an American flag with 48 stars (the number at the time) and, the following day, did so. He soon started depicting other “things the mind already knows,” familiar symbolic objects such as targets (his frequently reproduced “Target with Four Faces” of 1955 is here) and maps. While he made variation after variation, including drawings and prints — a large number of which are displayed — his signature medium was wax-based encaustic paint over collaged newspaper scraps.

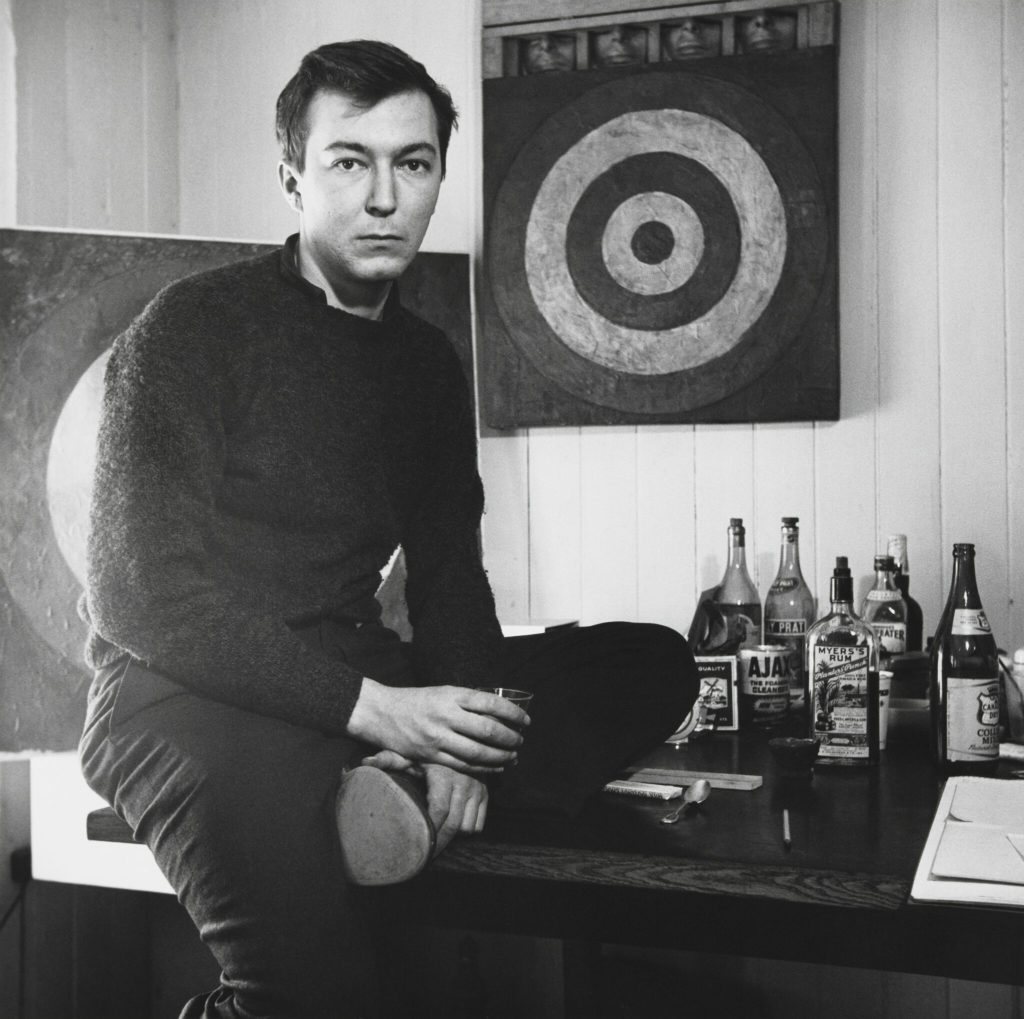

Target with Four Faces, by Jasper Johns (1955). Photo courtesy Whitney.org.

Inspired by the Dada creations of Marcel Duchamp, philosopher of art and manipulator of the mass-produced, Johns and his older co-conspirators — artist Robert Rauschenberg, composer John Cage and choreographer Merce Cunningham — sought to redefine art, music and dance. Rauschenberg, Cage and Cunningham had begun to do so at Black Mountain College in North Carolina in the late 1940s, around the time the Georgia-born Johns arrived in New York from South Carolina. After Korean War service in Japan, Johns returned and, in 1954, met Rauschenberg.

Rauschenberg and Johns, who became lovers, designed store-window displays to pay the bills. In adjacent Lower Manhattan studios, they explored the border between painting and sculpture, toying with found objects and pop-culture material. Following their lead, Warhol painted his “Campbell’s Soup Cans” (32 in number) and silkscreened his stack of wooden “Brillo Boxes” in the early 1960s.

One gallery is devoted to Johns’s wonderfully Rauschenbergian “According to What” of 1964, a six-panel assemblage (the hinged panel at lower left hangs open, revealing Duchamp’s profile) accompanied by preparatory and related works. To the canvas surface, painted with rectangles of primary colors, Abstract Expressionist patches, a column of graduated gray and a traffic-light pillar of colored circles, he has attached a coat hanger from which a spoon extends on a wire, part of an upside-down chair and three-dimensional letters reading (vertically): RED YELLOW BLUE.

Summer, from The Seasons. Photo courtesy Whitney.org.

Although in this work Johns shows a playful side, his mode is most often deadpan irony. The bitterness of the gray pieces he made when Rauschenberg left him in 1961 is therefore startling. On view from that year are the murky “Liar” (the word is stenciled under a flap), the smeared “Good Time Charley” (with an attached yardstick and inverted tin cup, on which the title is stamped) and the muddy “Painting Bitten by a Man” (defaced by a horrid tongue impression).

Johns’s friendship with Cunningham, Cage’s collaborator and lover, was a lasting one. He designed sets and costumes for Cunningham’s path-breaking dance company as artistic advisor from 1967 to 1980. His “Dancers on a Plane” of 1979, with a symmetric pattern of red, yellow and blue crosshatches (another Johns motif) and white plastic forks, knives and spoons embedded in the frame, is an homage to the choreographer.

Later works in the exhibition include examples of Johns’s “Catenary” series of the 1990s, generally blackboard-gray paintings with a string suspended in an arc from yardstick-like elements. In “Catenary (I Call to the Grave)” of 1998, he adds a “harlequin” diamond pattern at right and stencils the title’s parenthetic phrase, from “The Book of Job,” in barely perceptible gray along the bottom. Johns often challenges the viewer to look closely in order to grasp, if not penetrate, his obscure constructions.

At one end of the final gallery, a shoebox-shaped room with seating and a wall of windows overlooking the Hudson, is an aluminum recasting of “Numbers, 1964,” looking like a metallic calendar. The rows of this 11-by-11 grid, originally commissioned for Lincoln Center, repeat 01234567890 starting on successive numbers. Four free-standing, double-sided sections reworked from that piece by Johns between 2008 and 2012 and cast in silver, bronze and copper are spaced along the length of the room on pedestals.

At 91, Johns continues to paint and make prints with assistants (though not the assistant who went to prison for art theft) in his northwest Connecticut home and studio. The property, in the gentleman-farmer town of Sharon bordering New York, is to become an artists’ retreat after his death. His work has gone in other directions, as this exhibition documents, but it is Johns’s 60-plus-year obsession with instantly recognizable forms and symbols — American flags, Arabic numerals, ale cans — that seems most likely to endure.

“Jasper Johns: Mind/Mirror” runs through Feb. 13 at the Whitney Museum of American Art, 99 Gansevoort St., NY, NY 10014.