Fragments of Genius: Peter Brooks on the Duality of Samuel Beckett

By • July 26, 2011 0 2941

If you love the theater and its deeply felt surprises, then Samuel Beckett and Peter Brook are names that resonate. It’s not every day that two geniuses come so close together, the one resurrecting the work of the other, making emotionally visible.

Impressions and memories surface: Samuel Beckett, the first, best and last great avant garde playwright, the penman of Godot, created lingering fragments in the memory of our theater consciousness, dead since 1989.

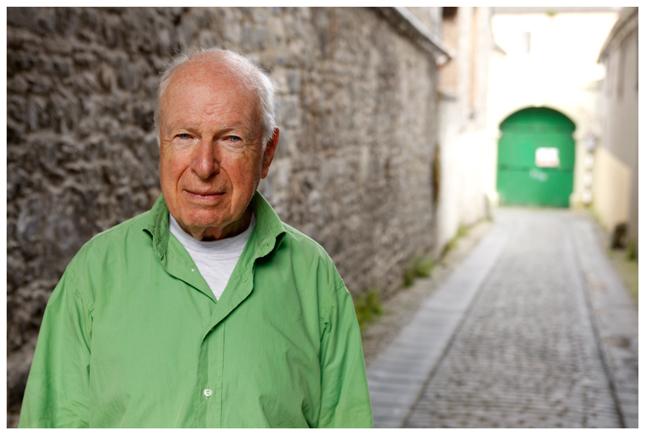

Then there’s Brook, the iconic stage and film director. He shook the old tree that was the Royal Shakespeare Theater with “Marat/Sade,” a crazed, energetic “Midsummer,” and then went to Paris to stage a huge theatrical version of the great Indian epic poem the “Mahabharata.” He is past 80 and as keenly coherent, stimulating, daring, brave and hopeful as he ever was. His life and career amount to a roaring sea of achievement in books, films, plays. He has produced epics that no one else would have dared to event think about, let alone execute.

And now, we have Beckett and Brook together at the Kennedy Center’s Eisenhower Theater with a production called “Fragments,” based on the text of five short works by Beckett, co-directed by Brook with Marie-Helen Estienne, with whom he worked on “Tierno Bokar,” a play about the life of the great Malian Sufi leader. “Fragments” originated with the Bouffes du Nort Theatre in Paris, which Brook had made the base for the International Centre for Theatre Research, which he founded in the 1970s. And of course, Brook knew Beckett.

“I knew Beckett, certainly,” Brook said in a telephone interview this week. “He was a friend, and he is very much with us now. He’s very important now in this time, but perhaps not in the way many people are used to thinking of him.” There’s something jaunty about his voice. It’s inviting, conversational, friendly, accessible.It’s as if you were chatting him up at a bar in Paris or Dublin, and you just naturally jumped in on Sartre, Genet, the avant garde, Sufism and Laurel and Hardy, among other things.

“I think to this day people think of him as this bleak, terrifying writer, this tragic Rasputin, full of pessimism and hopelessness and despair, a realist who showed us what was really going on in an age of optimism,” Brook said. “I think of it as Beckett 1 and Beckett 2. It’s the same Beckett, the plays and words, but they sound different. I knew him as a warm man, funny, witty. He was wonderful company, a good friend, he loved music, and he had a big sense of humor. He loved all these old Hollywood clowns, the mimes, the pratfall comics…Oliver and Hardy, he loved them.”

Listening to Brook, you think naturally enough of Vladimir and Estragon, lost protagonist tramps of “Waiting for Godot,” forever waiting for a Godlike character to appear to somehow change their live, save them from their misery and terror and keep them from killing themselves. Among many character traits, their plight may be bleak, but their talk is often funny. They move like hapless, helpless clowns, a ragged married couple caught in a horrible, repetitive vaudeville act. More often than not, they are like Laurel and Hardy faced with another fine mess.

“When ‘Godot’ and his plays and writings first had an impact, it was [around] the Post-World War II optimism spurred mainly by the United States,” Brook said. “There was all this prosperity and wealth, there was a noticeable and naïve optimism. There was also Jean Genet and Sartre and existentialism, which showed the stark mirror to the naïve optimism. And there was Beckett. His plays, his writings showed the other side, the despair, the sheer terror of modern life; it was a drastic, bleak contrast. But it was not the whole of Beckett.”

“Look around today,” Brook said. “Everything you see, everywhere you look, there is nothing but horrible news, terrifying news, and that optimism is plainly absent. So now we have Beckett II, if you will. Look at his characters: the woman in “Rockaby” (One of the plays in “Fragments,” and an unforgettable work that invades your subconscious like a squatter that never leaves), Winnie in “Happy Days,” up to her neck and immobile.

“Listen to her,” Brook says. “She can’t move, but she says ‘I want to be like a bird.’”

“They have persistence, in spite of everything. But more than that, there’s this enormous affirmation, and that affirmation is what’s important about Beckett now.”

Brook is 86 now, still going strong, having worked on a new version of “The Magic Flute” and the journeying “Fragments” production. He is known as a big thinker, a master of the grand idea put on stage, and absolutely fearless.

He is loaded down with honors, with the work, with this huge reputation—so much so that I hesitated before picking up the phone and dialing the number. In theater, Brook has some aspects that are sage-prophet-deity, which the Brook voice belies. The things he says to you he has said many times to many people, but because they remain radical, new, modern, it is not a familiar kiss.

He has written books on the theater—most famously “The Empty Space” and his autobiography. He has heated opinions, which are always sure to ruffle establishment feathers, and he has a history of battling with actors, critics, institutions and organizations. He is known for his work ethic, his pursuit of perfectionism. But in the midst of world revolution he seems to seek the route where toleration can thrive. The Sufis, for instance, are a branch of Islam that preaches toleration of other faiths.

“Fragments” seems such a wispy word for Beckett’s plays. Even the full-length plays—“Krapp’s Last Tape,” “Waiting for Godot,” “Happy Days”—seem to lack the complicated physical requirements of theater. You could stage them in utter darkness and still be devastated.

Every repetition, every word in Beckett’s plays seem to have the potential to explode, to expose feelings we’ve always kept covered. The “Fragments,” including one that’s a poem, are big things, dense with echoes. His shadow is big in odd ways, even in daily life and pop culture: I know a lawyer who named his pug-like dog after Beckett, and I remember graffiti in a DC Space bathroom that read: “I’ll be back.” It was signed “Godot.”

“Rockaby” is perhaps the best known works among the “Fragments,” which also include “Act Without Words II,” featuring two men in sacks and their adventures with a long pole. In “Rough For Theater I,” a blind man and a disabled man team up to form a functioning person. “Come and Go” features three women seated side by side on a narrow bench, and “Neither” is an 87-word poem that deals with the word “neither.”

“I can tell you that we’ve done interesting things with it,” he said of this staging of “Rockaby.” “But you’re going to see it, so I can’t tell you the specifics. You’ll have to wait and see.”

It struck me that this emphasis on what he sees as the complete Beckett, the affirmative prophet, may also be part of his own journey from head-on, even revolutionary and often shocking theater, to this notion of affirmation. He is known—like Beckett—to be a perfectionist and, as he wrote: “one can live by a passionate and absolute identification with a point of view.”

However, he writes, “There is an inner voice that murmurs, Don’t take it too seriously. Hold on tightly, let go lightly.”

“Fragments” is being performed at the Kennedy Center’s Eisenhower Theatre through April 17. Performances are April 14, 15 and 16 at 7:30 p.m. and April 16 and 17 at 1:30 p.m. For more information, visit [The Kennedy Center online.](http://www.kennedy-center.org/calendar/?fuseaction=showEvent&event=TLTSG)