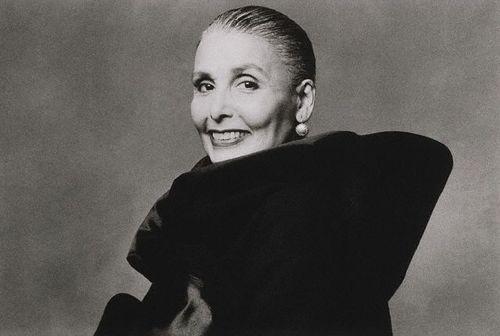

In the 1980s, Lena Horne, a pioneer, legend and star in her mid-60s, put on a one-woman show called “Lena Horne: The Lady and Her Music,” which became the longest-running solo performance in Broadway history.

She brought the show to the Warner Theatre in Washington, and if you had the good fortune to experience it (and that’s the right word), you got the essence of Horne, and a pretty good idea of what courage and perseverance were required to succeed in America if you happened to be black or of mixed race parentage and if you happened to be born early in the last century.

Horne brought all of her life experience, her humor, her still-burning bright beauty, her vocal abilities and her shazam style to the performance. She sang her signature song “Stormy Weather” twice during the course of the night. “I was young when I first sang it,” she said, and sang it right there like a naïve, lovely young girl, and sang it again, all the stormy weather she had experienced herself at full throat. “This is me now,” she said.

Horne came from a mixed marriage, and was married at one time to Lennie Hayton, a top conductor and arranger at MGM when the studio’s musicals where American landmarks.

When it came to civil rights and racial history, she was a little like Zelig, being everywhere: she was a Cotton Club chorine, she was both famous and half visible as an MGM starlet and star, including Vincente Minnelli’s “Cabin in the Sky” and “Panama Hattie,” in which she sang “Stormy Weather.” She was in numerous MGM musicals, but her roles tended to have the position of production numbers, which could be cut if the films where shown in the segregated South (and they were).

In the 1940s she worked with the controversial and politically active singer and performer Paul Robeson, a man of huge gifts and anger. She made United Service Organizations tour stops (where German POWs were routinely seated in front of African American soldiers), a task at which she balked.

She took part in the dramatic civil rights marches of the 1960s and sang on behalf of the National Council of Negro Women and the NAACP.

Her music, once she stopped making Technicolor movies, was beyond category, beyond jazz and completely enduring. She recorded well into her 80s.

Through all the trials and tribulations, the difficulties that were part of her life, she never succumbed to such shallow notions as complaining. She just kept on doing what she loved, stood up tall, and was dazzlingly emblematic of class, as in classy, as in first class.