Former Senator Charles Percy died Saturday at the age of 91, succumbing to the effects of Alzheimer’s disease at a local hospice.

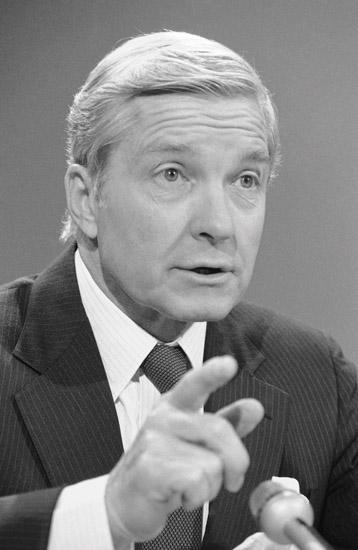

In the media much was made of the fact that Percy, who was elected to the Senate from Illinois in 1966 and served three terms, was once seen as a man of enough gravitas and appeal to be a presidential candidate, and that he was a rare breed amongt politicians today, almost invisible to the naked eye, a moderate-bordering-on-liberal Republican.

Even after he was defeated in a grueling bid for a fourth term in 1985 by Democrat Paul Simon, Percy was always referred to as Senator in greetings, meetings and walkabouts in Georgetown, where he and his wife settled happily when he first came to Washington.

Senator Percy had several careers and achievements outside the Senate. In addition to heading up a Washington-based trade and technology investment-consulting firm after his departure from the Senate, he also took on another role, one in which he took great pride. Percy became the good citizen of Georgetown, a role which he embraced with ardor, decency, and a commitment to the idea of community—an ideal that permeated all his efforts, whether working with the nation, a major business, or a self-described village in Washington, D.C.

For Georgetown, Percy provided leadership for the drive to create a livable, viable, ecologically sound and beautiful Waterfront Park. The $24 million, 9.5 acre park, a joint project of the National Park Service, the Friends of the Georgetown Waterfront Park and the District of Columbia, opened officially September 23, even as Senator Percy lay dying, giving the occasion an atmosphere of deep and mixed emotions amidst the celebration.

The occasion showed that a man’s life—even a Senator and presidential candidate—is not lived in one arena, one place and with one heart. Percy’s life was a classic story: he was a World War II veteran as an ensign in the U.S. Navy, he had a newspaper route, and he was a lifelong Republican who believed in the American success story and the virtues of American entrepreneurship that existed in his youth. Small wonder—in 1947 at the age of 29, he had risen to the president’s chair of Bell & Howell, one of America’s largest firms.

He first entered politics in a failed but close attempt to unseat Democrat Otto Kerner, Jr. for the governorship of Illinois. He defeated the venerable Paul Douglas for the Illinois Senate seat in 1966 and won two more terms, before being defeated his fourth term run.

As a Senator, he became what was then called a Rockefeller GOP liberal: pro-business, but moderate-to-liberal on social issues and, unlike many fellow Republicans, skeptical about the war in Vietnam. He called for an independent investigation of the Watergate scandal, going against a Republican president. For this, he had the honor of making Nixon’s Enemies List.

Time Magazine put him on their cover and, as a handsome, articulate and appealing bipartisan spokesman, he was often talked about as a presidential candidate. In an interview with the Georgetowner over a decade ago, he admitted that he had thought about it seriously but refused to challenge Gerald Ford for the nomination. In this, as in many things, he was different from future president Ronald Reagan. He was proud of having created legislation that created NPR, and even more proud of his daughter Sharon, who not only married a Rockefeller, but became president of WETA.

However, tragedy struck at the height of Percy’s success when, during his first Senate campaign, his 21-year-old daughter Valerie, twin to Sharon, was found murdered in her bed at the family home in Kenilworth. The murder was never solved.

“No one would have loved more to be here front and center [than my father],” said Percy’s daughter Sharon at the park dedication. “He would have been thrilled to see this magnificent setting. It is his fondest and last best work.”

A plaque in his honor at the park reads, in part: “Senator Charles H. Percy was pivotal in the creation of the Georgetown Waterfront Park. Senator Percy—a Georgetown resident, lover of the waterfront, and supporter of local high school rowing—chaired the Georgetown Waterfront Park Commission that was so instrumental in the park’s creation.”

Georgetown architect Outerbridge Horsey remembered going to Percy downtown with the late architect Bill Cochran to ask Percy to take on the leadership role in the waterfront project. “He was very amenable and agreeable,” Horsey said. “And he wasn’t just a figurehead with a famous name. He chaired every meeting in the early years until he resigned, and he had that voice and bearing of authority which got people to work together. He was very much a good citizen and member of the Georgetown community.”

He was also a regular and often vocal presence at CAG meetings, once famously calling a meeting to order with an ear-piercing whistle, which, like Percy’s moderation, is a disappearing skill. Sometimes, he would set himself down and start playing the church piano before meetings.

If Alzheimer’s is a disease that robs its victims of memory, then let us remember now Charles Harting Percy, father, husband, Senator, businessman, moderate Republican, philanthropist, and good citizen of Georgetown.