Secrets of the Double White

By • November 3, 2011 0 1595

At the Phillips Collection, there is a double feature of (almost) white painting with Richard Pousette-Dart and Robert Ryman occupying different floors within the museum (1600 21st St., through Sept. 12.) It is the differences between the two artists that enhance the choice of having both exhibitions at once. In conjunction with the show, Yasmina Reza’s “Art,” a play focused on how a white painting puts friendship to the test, will perform at the Phillips on July 1 at 6:30 p.m.

White is not a color often featured in Western painting before the 20th century. It usually is found in paintings in clouds with tints, on the highlights in objects and sometimes in snow. Here it stands alone, or almost alone. Robert Ryman’s show is the best Ryman show I have ever seen. This is possibly because of the small scale of the work that allows you to pay more attention to how the paintings are painted. One can focus on the edge that is painted, the threads that stick up from the frayed canvas, and the actual strokes that tell far more.

Here Ryman astutely contemplates painterly means, and he is sometimes lyrical in a fumbling manner. His small works have the dramatic tension of a stage whisper. For me it is the all-black Jasper Johns and Robert Motherwell (of the “Iberia” series) that mentor Ryman, especially in his early works. Ryman is closer to Johns in being emotionally deadpan. Motherwell had more range than Johns or Ryman. And unlike Johns or Motherwell, Ryman does have one of the all-time worst signatures in art — very junior-high-school. Nevertheless, Ryman has had a huge influence on the look of abstract painting of the last 40 years; you see his pokerfaced progeny everywhere.

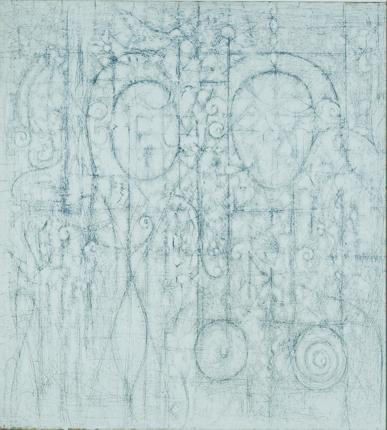

Visiting these shows for the third time, it is Pousette-Dart’s work that holds repeated viewing. With Pousette-Dart there is real experimentation with technique and an openness of the possibilities of painting. His extensive drawing with graphite into the final, rather than the preliminary, aspect of painting was innovative. His few sculptures are worthy of inclusion, not just sidepieces. They have a direct relation to the paintings, though they are lighter hearted.

In Pousette-Dart’s sculpture and the painting, there is overt and covert figuration. One work is divided with a male and female figure splitting the canvas, yet meshing in the web of space. There are biomorphic forms in most of the paintings. Visible is the common heritage of abstract-surrealism derived from Picasso and Miró. But it is Pollock and his allover drip paintings from the late forties that inform the structure of some of the greatest of Pousette-Dart’s almost-white paintings. Somehow he could easily integrate Pollock’s great reckless expanses into his much more intimate quest.

Pousette-Dart’s line is deft and unlyric but weighted and incisive. His use of space is always dynamic and active and his pictures activate the space around them. A painting should have secrets, and these wry and sometimes quietly joyful pictures do contain enough to warrant real looking.

- Pousette-Dart, “Quiet Lovers” (1950-51) | © 2010 Estate of Richard Pousette-Dart

- Jordan Wright