In Arena’s ‘Red,’ Actors Energized by Talk, Ideas and Art

By • February 8, 2012 0 1026

Newt Gingrich talks a lot about being a man of big ideas, how he embraces them, gives birth to them and spouts them morning, noon and night.

He ought to come over to Arena Stage and see “Red,” John Logan’s play about the raging, despairing, non-stop talking abstract expressionist artist Mark Rothko in crisis, as he takes on a critical mural project and a new assistant.

Talk — and there’s a lot of wonderful, powerful talk — about big ideas. It’s enough to make a politician realize just how small his ideas really are.

“Red,” directed by Robert Falls, the gifted artistic director of the Goodman Theater in Chicago, is a two-character play about Rothko, arguably the star member of the generation of American painters whose abstract expressionist breakthroughs put New York at the center of the art world once defined by Paris.

Rothko, with his huge and mysterious paintings of emotional color fields achieved fame, if not understanding, early, became, along with the erratic Jackson Pollock and his action paintings, a rock star of a movement that was already being threatened by yet another next, new thing, the rising work and fame of pop art stars, such as Warhol, Lichtenstein, Rauschenberg and others.

When we see Rothko, alone in a chair staring at a canvas, he is arguably one of the most famous living artists in the world. Pop art is on the horizon, and Rothko has taken on, for big money at the time, a commission to create a series of murals for the Four Seasons restaurant in the new Seagram Building.

In “Red” — the murals are varations on the color, a kind of combat between dark and light as well — we see Rothko in full with all of his famous imperfections: the grandiosity, the urge not only to talk but to make pronouncements, his famed insecurity and egomania always warring, the contempt for other artists, critics, intellectuals and so on. We see him through him, and through the eyes of a new assistant, a sharply-edged dynamo named Ken, an aspiring artist himself, a fact that Rothko notes and ignores.

Most people, either by reading the program information or just by more than a passing interest in modern art will know that Rothko’s story ends badly — a suicide in his late 60s in 1970, adding the last dose of tragedy and drama to the story of the expressionists. There’s a sense of urgency to the proceedings, especially when he’s talking about Pollock’s possibly suicidal death in a car crash, and in a scene that seems almost horrifically prophetic, paint being mistaken for blood.

What you get here is theater — about art and an artist and the artistic impulse. It’s pretty inventive stuff, high theater and drama as well as high-mindedness, all of it executed at a level of kinetic, intimate physicality.

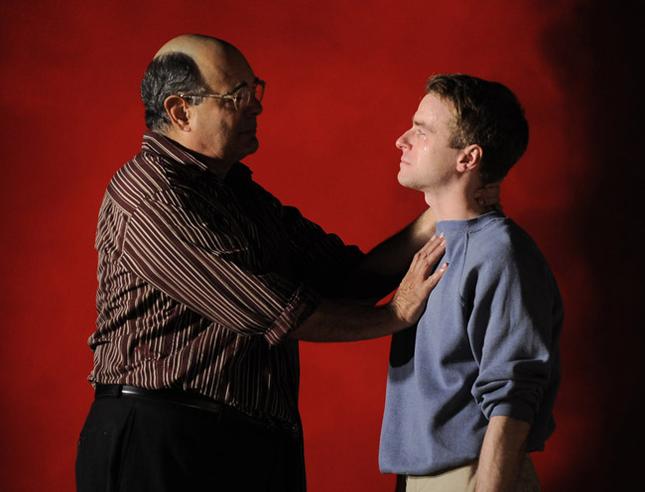

Looking at these two artists — Ken is a young man who’s embraced the new art, he has a back story of murdered parents — you see a father-son rivalry as Ken, with thin, tensile strength like tough wire, challenges Rothko right where he lives, in his most cherished views of himself as an art-philosopher, a serious beyond serious man. That’s Rothko’s gripe about the pop artists who have achieved fame without being serious, a notion that Warhol for one would find ironically hilarious.

Ken’s continuous challenges seem at first fresh, an affront to a god, but he earns the right by sweating with Rothko, doing everything he wants, sharing his passions. There is no better scene about art in a play than the occasion when the two, like sweaty street rats, set about priming a huge canvas with paint — it’s a choreographed dance, it’s heated, almost desperate and beautiful, it’s almost a mating exercise, not with each other but with the canvas and the paint. It’s a shared moment, an intimate contact with paint which leaves both men splattered, they look like a shaman and his assistant in the dark arts.

Ken’s main and biting attack on Rothko is his betrayal of his own art by taking on a $30,000 commission. Rothko thinks he’s creating a cathedral for his works, an idea at which Ken scoffs. Rothko wants the diners to sit in awe of his work, having lost their appetite for everything else. In the end, Rothko, historically and in this play, gives back the money and won’t have his work in the Four Seasons.

Edward Gero, the long-working Washington actor who seems to be saving his best work for the latter part of his career, gives a bullish, bravura performance, the intellectual as hard-nosed verbal street fighter, defending Nietzche, discussing Apollo, drinking hard, working harder, hardly ever at rest. It’s a great performance matched sharply by Patrick Andrew as Ken. He’s prickly. His skepticism is like a coat of porcupine needles.

The set by designer by Todd Rosenthal is a lived-in, worked-in cathedral, informed and haloed by Rothko’s art and by the sweaty reality of the workaday artist’s studio.

“What do you see?” Rothko asks more than once. “I see red,” Ken says. In the play, we see a lot more. Going to places like the National Gallery of Art or the Phillips Collection in Washington, where you can find Rothko’s haunting work, you might ask yourself a different question: “What do you feel?”

“Red” will be performed in the Kreeger Theater at Arena Stage through March 11.

- Edward Gero as Mark Rothko and Patrick Andrews as Ken in the 2011 Goodman Theatre production of Red. Directed by Robert Falls. | Liz Lauren