Edgar Degas at the Phillips Collection

By • May 3, 2012 0 2245

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

As geniuses tend to be, Edgar Degas was a compulsive revisionist. Returning to his canvases again and again, often over the course of decades, the artist left behind a wealth of visual pathways into his process upon his death in 1917. As geniuses tend to be, Degas was also a bit of a contradiction. He was a founding member of the Impressionist movement, though he vehemently rejected the label and his association with it.

Degas was a champion of an artistic revolution that moved painting beyond the gratifying of patrons and into the realm of true artistic exploration, paving the way for the explosion of cubism, abstract expressionism and beyond. He fought among critic circles for the collective reputation and legitimacy of himself and his colleagues—Monet, Renoir and Delacroix to name a few—and produced among his most acclaimed works in this time (roughly 1870s – 1880s). Yet he called himself a “realist” and rejected comparisons among his contemporaries. “What I do is the result of reflection and the study of the great masters,” he said.

But within each individual work, Degas managed to embody the monumental nature of artistic practice; he achieved a harmony and perfection of nature through practice, observation, trial, revision and an ever-scrutinizing eye.

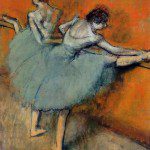

His methodical, repetitive practice is frequently compared to the subject of his recurring painterly infatuation, the ballet dancer. While the spontaneity of his compositions may seem frozen precipitously in time—his ballerinas in imperfect repose between moments of rehearsal, turning out, warming up, preoccupied with nothing beyond their physical composition—the delicate beauty of these moments turn out to be nothing less than the result of countless studies and immeasurable, tedious compositional revisions. This relentless strive toward an ephemeral balance, delicate as the air floating about the plane of the canvas, is illuminated remarkably in the Phillips Collection’s current retrospective of his ballet paintings, focused around his seminal work, ‘Dancers at the Barre.’

“No art is less spontaneous than mine,” Degas once said. It would seem fitting then that he was focused so irrevocably on professional dancers. The effusive, explosive nature of a pirouette, for instance, must be fluid and natural within the movement of the dance, but that graceful fluidity is something that only comes with obsessive, endless practice and repetition. And Degas painted not the climax of the twirl, but the tenuous moments leading up to it—the revision, the edits, the scrutiny of practice. And he painted it within its own terms.

Upon entering the third floor of the Phillips Collection, which has devoted the entire level to the exhibition, you immediately come upon the ‘Dancers at the Barre’ painting, the two ballerinas stretching side by side in their matching blue practice skirts. On the other walls of the room hang two other studies of the same scene, one nearly identical in composition, and one of the central model posing nude in the same stance.

Throughout the exhibition, the Phillips chose to highlight Degas’ variation and repetition, even exhibiting infrared and x-ray photos of a number of the artist’s paintings to show them in their various stages of completion, exposing the way he moved and positioned his subjects about the canvas as well as their own axis—the adjustment of a leg, the arch of a back, the direction of a subject’s hair.

There is also a large showcase of the connections made to Degas within the ballet in recent years, focused around a video of acclaimed choreographer Christopher Wheeldon’s 2004 production of ‘Swan Lake’ at the Pennsylvania Ballet, which conceived its costumes and sets reminiscent of the nineteenth century Paris Opera as depicted by Degas.

But the crowning achievement of this exhibition is exactly what it should be: the collection of the artist’s works brought together for this stunning exhibit. The beauty and wonder of Degas is heroically and intimately displayed, showcasing his most acclaimed paintings alongside his sketches, prints, charcoal drawings and enticingly tactile sculptures. It is an exhibit that shows us the complete portrait of not just the subjects, but of the artist.

“Conversation in real life is full of half-finished sentences and overlapping talk,” said Degas. “Why shouldn’t painting be too?” This is an exhibit for those of us who want to experience the full conversation, and long to fall into a fierce, satisfying discussion with Degas in his own time.

Degas’s Dancers at the Barre: Point and Counterpoint, will be at The Phillips Collection, 1600 21st St. NW, through Jan. 8, 2012. For more information visit PhillipsCollection.org.

- Hilaire-Germain-Edgar Degas, The Dance Class, c. 1873, Oil on canvas, 18 3/4 x 24 1/2 in. Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., William A. Clark Collection.

- The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.