National Gallery Opens Landmark Exhibits

By • May 3, 2012 0 1502

Lions and tigers and bears, oh my. Come January 29, there will be a similar song to sing at the National Gallery of Art: Picasso and Castiglione and the newly renovated French Galleries, oh me, oh my.

A rich time machine and evidential exhibition explores and nails down Pablo Picasso’s reputation as the greatest draftsman of the 20th Century in “Picasso’s Drawings, 1890-1921: Reinventing Tradition,” an exhibition of some 60 works, spanning the first 30 years of his career riding straight to the doorsteps of impending legend-hood.

In “The Baroque Genius of Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione,” lies an exploration of sources and influences, in the varied, kinetic exhibition with 80 works culled from the galleries extensive holdings of works by the Italian master, that also includes works by contemporaries and followers.

There is no title for the newly renovated and installed French Galleries, the culmination of a two-year project that enriches, rearranges and creates dialogue among the Gallery’s nearly 400 impressionist and post-impressionist holdings. “Greatest Hits” surely would not do, but the fact that the collection in the West Building’s second floor now carries with it a kind of path of themes, stories, and regularly spaced explosions of recognized and acknowledged masterpieces seems to demand a worthy title.

There is no connection among the two exhibitions and the reopening of the French galleries, although Picasso, among many, is a strong presence there—he is at once the Jesus and John the Baptist of modernism, after all. And you could easily plug in the energetic lines and brushstrokes present in almost all of Castiglione’s work to Picasso’s drawings to ignite a spark.

The boy genius is very much evident in the Picasso exhibition, as is the man who, if he did not entirely invent cubism, surely gave it a good kick into the stratosphere. It’s an interesting process to watch, from the perfectly and finely rendered work of an 11-year-old child to the cubist works where he swims like a fish on fire. There are many nudes and near classical drawings of women here that, whatever and whomever the drawing are about, are always at least a little (and often very) sexually charged. Picasso—with a reputation that might explain a lot—could manage the not-so-easy task of creating allure and sex appeal in a cubist woman, fully twisted in negligee and disquietingly recognizable nightwear, replete with all their jagged, ragged edges.

Picasso’s early lines—a bust infused with the classics surely remembered from his studies, a restrained portrait of a woman—are clean, and never quite without emotion. See the son and father self-portrait, and then a father rendered by the son. You will see the connection.

Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione lived through the better part of the 1600s and included among his sources Rembrandt’s religious works. Seen side by side, you can easily see the connection. But he was also a source of inspiration for later artists, most notably Tiepolo and the still later French painter Antoine Watteau.

He belongs in the baroque, in terms of a recognizable genre and style, and his themes and subjects are like that of his contemporaries, religious and familiar: The Adoration, The Gifts of the Magi, the Crucifixion, and nativities of all sorts. But there’s a difference beyond categorization. Castiglione’s works are never still, not even perhaps when they should be. There’s an electric current running through them—shepherds leaning to get a better look, figures stretching, on the move, necks craning, in scenes that are essentially moments of peace.

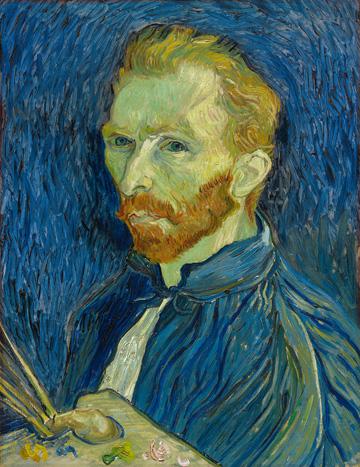

What is there to say about the French galleries? That you will be overwhelmed, awed, delighted or turned on? That you will be returning again and again, and so will everyone else? These artists speak to us, surely, but they speak to each other, too. In the gallery live Van Gogh, Gauguin and late Degas works, the one intense, the other pushy and Degas quietly off to the side, away from the noisy brawl.

There are so many paintings here that are almost cliché at this point: Renoir’s blue girl, the harlequins of Picasso. It’s almost as if you shouldn’t love them so much and move on to something important like the Oscar nominations. But they draw you in—Van Gogh’s self portrait, Renoir’s cityscapes, like Point Neuf paired with the Pont des Arts.

In many ways, the renovation is an exhibition, about the trip from the classics to the impressionists to the post-impressionists. It’s about stunning landscapes in the early days. It’s about women, most definitely. It is why, with every new movement in the fine art world, with every infatuation with the next big thing, we always come back here.

Many of the works in the galleries were on view while the work of restoration went on over the past two years in the West Wing, in the exhibition, “From Impressionism to Modernism: The Chester Dale Collection.” That installation was easily the best exhibition in Washington for the past two years.

In the French Galleries, it’s Degas, Monet, Manet and Matisse, oh my. And all the rest, oh my, oh my.

For more information visit NGA.gov.

- Courtney Overcash

- Vincent Van Gogh, ‘Self-Portrait,’ 1889. | Images courtesy of the National Gallery of Art.