The Meaning of Flag Day for Georgetown and D.C.

By • June 18, 2012 One Comment 2571

As the nation has begun its celebration of the bicentennial of the War of 1812, which gave us “The Star-Spangled Banner,” we also observe Flag Day. It is designated June 14 because of the 1777 resolution by the Continental Congress which established the design of the U.S. flag on that day.

While there was a D.C. flag tattoo flash mob, that started today at 5 p.m. at Dupont Circle, there are some serious thing to know about the flag and its role in American history.

To say that the flag is an emotional symbol for Americans is an understatement. For many, the flag is perceived and handled almost as if it were a sacred object. There are general rules on how to display or store the flag. While there are few legal constrictions on treatment of the flag, one who mistreats or shows disrespect in public to the Stars-and-Stripes does so at his own peril.

Georgetown has played its part in the history of the flag. It was home to the author of the national anthem, which celebrates Fort McHenry’s stand against the British as well as the triumphant flag which still waved over the fort at the end of the fight. His name was Francis Scott Key and lived on what become known as M Street next to where a bridge and a park would be named in his honor.

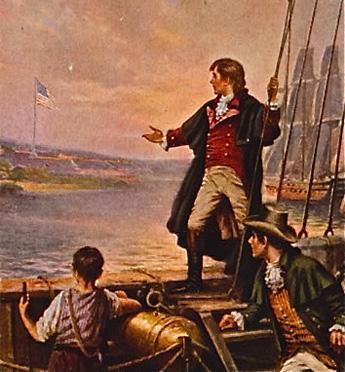

After the burning of public buildings in the new capital city, Washington, D.C., in August 1814, the Royal Navy and British army prepared to attack the bigger city of Baltimore in the days before Sept. 14. Meanwhile, as the British roamed around Chesapeake Bay and Maryland, they had captured a town leader, Dr. William Beanes, from Upper Marlboro, prompting a presidential group to seek his release. President James Madison had asked Georgetown lawyer Francis Scott Key to meet the British and negotiate his release. While with British officers on their ship near Fort McHenry, which guarded Baltimore harbor, Key could not leave and witnessed the bombardment of Fort McHenry. After the British push on land to Baltimore City was stymied, the navy stayed out of range of the fort and hit it repeatedly but failed to pass its defense.

Ending an evening of terrible explosions, lights and sounds, the British gave up the fight and withdrew in the morning. As “the dawn’s early light” revealed that Fort McHenry had stood its ground, Key was elated to see “that our flag was still there.” A large American flag — the Star-Spangled Banner — waved atop the fort. It was a moment of profound relief for the Americans. This war revealed one of the first times that Americans had acted as Americans — a fresh national identity — and not just as Marylanders, Virginians or New Yorkers. Key wrote these sentiments into his poem, “The Defense of Fort McHenry,” which was quickly renamed “The Star-Spangled Banner.” It become an instant hit, an army musical standard and finally the national anthem.

Key lived with his large family in Georgetown, D.C., from 1804 to around 1833 with his wife Polly and their six sons and five daughters. Their land was across from what is now the Car Barn (3500 block of M Street) and their backyard went all the way to the Potomac River (the C&O Canal did not yet exist). An accomplished lawyer, a true gentleman, scholar and fine orator, he was involved in church and community in the small town of 5,000 Georgetowners. He was the district attorney for Washington under the Jackson and Van Buren administrations.

Years later, business leaders and the Georgetowner newspaper founded “Star-Spangled Banner Days” to celebrate the flag, the anthem and its author, a hometown hero. In 1993, Francis Scott Key Park was completed and dedicated on M Street — one block from his famous home, demolished in 1947 — between 34th street and Key Bridge.

Today, Francis Scott Key Park and the Star-Spangled Banner Monument is a D.C. and national salute to the flag, the anthem and the man with its percola, bust of Key and a flag pole which flies a Star-Spangled Banner. That original flag, which inspired Key’s song, is on display about 25 city blocks away at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. Passers-by can rest and meet at this Georgetown oasis and recall a time when a young city and country had confronted its own years of war and lived through it to thrive and create a great nation.

- From a British vessel outside Baltimore harbor, Francis Scott Key observed the flag still waving above Fort McHenry in a romanticized historical image.

- Robert Devaney

Nice write up, Robert. As you well remember, we had a number of friends onllasaociated with the Francis Scott Key Park Foundation including our close friend Paul Hartstall. Paul would have been delighted with you article honoring their efforts!