Walking the Dog: Six Degrees of Separation

By • June 18, 2013 0 1188

The other night, just before round two of the load of rain dumped by a tropical depression over the Washington region, I managed to get Bailey, my 14-year-old Bichon, out for a much needed walk.

I learn a lot from Bailey. We’re nearing the Exxon gas station at twilight when we see two little children getting out of an SUV. “Hey, it’s Bailey,” or something like that, yells Patrick, who is nearing all of three.

His friend turns and says, “Wow, I didn’t know we were going to run into Bailey.”

Talk about enduring fame. In our Lanier Heights neighborhood, as I’m sure it is elsewhere, dog owners are not always greeted by name, but their dogs are. Everyone, in short, knows Bailey. But a surprising many people struggle with my name, which is both a curse and blessing. I feel like Jack Kennedy when he said, “I’m the man who accompanied Jacqueline Kennedy to Paris.” I am the man who walks Bailey around the block.

Bailey’s very localized appeal made me think about the nature of fame — how it is sometimes fleeting, sometimes lasting, and sometimes recurring. In America, there are first acts, second acts and more — and always last acts, in which famous people have their achievements and infamy reprised after duly passing away. Often, given the state of vitamins and good medicine, these famous people haven’t been heard from in a while. People live longer, die later. Or as Tony Curtis, a true old school movie star, said recently, “In this town [Hollywood], you have to die before somebody says something good about you.”

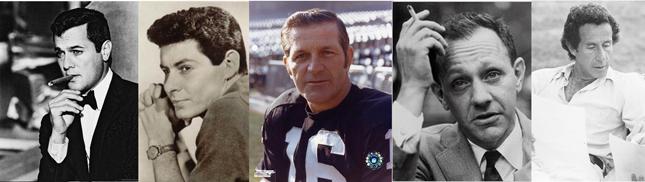

So, herewith, we give you a little of the life and times of: Tony Curtis, Eddie Fisher, George Blanda, Vance Bourjaily, and Arthur Penn — American success stories all. A movie star, crooner, football quarterback-kicker, novelist, and film-stage-television director — all of them fell victim to health issues in their eighties, the best parts of their professional lives long over, but endured in the memories of people, who themselves are, well…getting older.

I believe in the six degrees of separation bit. Somewhere there is a connection, however distant or intimate.

So let’s begin with Tony Curtis, matinee idol, New Yorker kid, sailor boy, Universal Pictures studio creation, terrific-at-times actor, lover boy (married six times), artist, and underappreciated. Think of Curtis and, as a moviegoer, you immediately see him fending off Laurence Olivier in “Spartacus” (“I am Antoninus, singer of songs, hard g’s clanking on Roman marble.”), or seducing Marilyn Monroe in “Some Like It Hot”, the Billy Wilder classic comedy in which Curtis and Lemmon pretended to be female musicians in an all-girl band during prohibition. You think of the oily huckster in “Sweet Smell of Success” , the bigot Southern convict chained to Sidney Poitier, on the run in “The Defiant Ones”, the creepy title role in “The Boston Strangler” — a pretty good body of work right there.

Curtis rose in the studio system that trained him, a pretty boy with pitch-black wavy hair, blue eyes, and attitude, growing up poor in Manhattan. He became a movie star and never spent much time resisting its temptations or opportunities. He was almost as pretty as Leigh, a beauty sometimes burdened by a bosomy build and a much underrated talent (witness her work on “Psycho”). The marriage did produce Jamie Lee Curtis, who played Lindsay Lohan’s mom before Lohan became a train wreck.

We saw Curtis here during the opening week of the World War II Memorial, when he was at the Navy Memorial for the annual commemoration of the Battle of Midway. Curtis, who was born as Bernie Schwartz, was a sailor in the U.S. Navy in World War II and spoke movingly, thanking the navy for letting a poor kid from New York “expand his horizons, see the world and its possibilities.” Here, he was both things at once: movie star incarnate in dazzling old age, alligator cowboy boots, a big cowboy hat, and tanned with his gorgeous, thirty-ish wife beside him, and Bernie Schwartz, sailor boy.

Curtis died in Henderson, Nevada, where my son lives. Six degrees.

I vaguely listened to Eddie Fisher’s records when he was one of the country’s top crooners. “Oh My Papa” was everybody’s favorite, and young girls and mothers both adored him. This was pre-rock and roll, pre-Elvis, early 1950s: Fisher was dark-haired, handsome, with a stylish, moving voice and a way with a soaring, moving ballad. He was a teen idol before old swivel hips came along and ruined it all for a generation of lesser singers like Vic Damone and Johnny Ray.

Few people remember his musical career, which continued at lesser levels with albums, Las Vegas, and hotel show rooms. Fisher was something of a rat pack wannabe in his day, and, like Curtis, something of a dog with the ladies. What people really remember is: Debbie, Mike, Liz, and Dick. The paparazzi that existed in those days, from the mid-fifties to the early sixties, had a field day, and Fisher got bowled over like a gasping fish by the whole thing, with nobody to blame but himself.

Fisher married just about the nicest young girl around, a miss Debbie Reynolds, and together (with Curtis and Leigh a close second at the time) they became America’s Sweethearts — clean-cut, shiny teeth, and hugs with babies (daughter Carrie). Eddie had a best friend named Michael Todd, a larger-than-life Broadway and film producer who made “Around the World in Eighty Days” (Best Picture Oscar), married the reigning movie star of the day, Elizabeth Taylor, and promptly got killed in a plane crash. Eddie consoled the widow and then consoled her some more, much to the public chagrin of wife Debbie. They divorced, Eddie married Liz, and both became vilified in the public eye — especially Eddie, the cad. The whole thing was the biggest scandal ever, until the next one.

Liz redeemed herself professionally by playing a hooker in “Butterfield Eight” and winning an Oscar. Then she moved to Rome to make the ruinous, hugely expensive “Cleopatra”. While filming, she met Richard Burton, her Anthony, and promptly began a hot, heavy, and very public affair, much to the chagrin of husband Eddie — the perfect storm of all scandals, excluding Brangelina. Six degrees.

I sat in on a press conference in San Francisco in the 1970s for Debbie Reynolds, who was touring the country in the musical “Irene” with her daughter Carrie. I recall her very funny and forthright answer to the clichéd question about how she might change her life if she had to do it all over again. “Well,” she said with a straight-face, “I’d probably screw around a lot more.” Jaws dropped onto the hotel’s red carpet.

More recently, I saw Carrie Fisher, daughter of Eddie and Debbie, perform her one-woman show “Wishful Drinking” at the Lincoln Theater, which included acerbic anecdotes about Hollywood and a childhood with famous parents. Fisher already has a very permanent, red-hot kind of fame from her role as Princess Leia, in the 1980s “Star Wars” Trilogy. Perhaps some might even remember her very first lines in her very first movie “Shampoo.”

It turns out Curtis was more right than he knew. On Access Hollywood, the most shameful guilty pleasure and half-hour showbiz-and-buzz TV show featuring the one-time Christian music deejay and Bush family relation Billy Bush, you had to wait until the end to hear a less-than-a-minute tribute to the life and times of Curtis. The show and Billy were preoccupied with such matters as Paris Hilton’s car riding over the toe of a paparazzi, whether “Glee,” the hit Fox show, crossed the too-nasty-for-kids line in its Britney Spears tribute, and advice for Lindsay Lohan from Donald Trump. So it goes, and so it went.

I saw George Blanda, then in his forties, sub for Daryl (dubbed footsteps) Lamonica as quarterback for the pre-Kenny Stabler Oakland Raiders and had occasion to watch the old man from the sidelines on several occasions. He won games throwing, he won games kicking, and he played until he was 48 years old. An NFL owner, who had hired him originally, said he remembered in the 1970s that his father had played in the 1950s. He had a butch haircut like Johnny Unitas and craggy features: quarterbacks from that era, like Y.A. Tittle of the Giants and Unitas of the Colts, were born looking like marines. Blanda had the dubious fortune of playing for Al Davis, the only football owner that makes Dan Snyder look like Mother Theresa. I was kicked out of his office once during training camp when I was a young sports writer. That would be two degrees.

Davis, legend has it, came home once in the wee hours, and his sleeping wife reportedly moaned “God” in her sleep. “You can call me Al at home,” said Davis. I believe it.

Vance Bourjaily was of that generation of American post-World War II writers, many of them veterans, who pursued the dream of the G.A.N. (That’s not Good Morning America but the Great American Novel.) He tried hard, and sometimes movingly, and belongs in the ranks of writers like Updike, Mailer, Bellow, James Jones, and one of the surviving members, Philip Roth. Like them, Bourjaily, in novels like “The End of My Life”, “The Violated”, and “The Man Who Knew Kennedy”, wrote frankly about sex, which made their books must-reads for young men growing up in that era, in addition to their literary value. I read all of them and still didn’t learn everything there was to know. One Degree.

If “Bonnie and Clyde” was the only movie he ever directed, Arthur Penn would still be in some kind of pantheon, just for changing the movie culture of the 1960s. To say the film was revolutionary — a romanticized, stylized, sexy, and ultra-violent telling of the tale of Depression era bank robbers, with hunky Warren Beatty and super sexy Faye Dunaway in the leads — is an understatement. Time Magazine ran a highly negative review, then reversed itself. It’s one of the best movies ever made.

Penn became known as something of a liberal, leftist, counter-culture kind of force as a director. He captured the sixties zeitgeist, always a favorite word of the critics who praised him. He also directed “Alice’s Restaurant” and “The Miracle Worker”.

Penn was also a close friend of the controversial state department official Alger Hiss, who was convicted, in the early days of the McCarthy era, of being a Communist spy. Hiss always declared his innocence. Three degrees. I had a lengthy and haunting interview with Hiss at American University in the early 1980s.

And so it goes.