‘This Town’ Is In Our Town, Just Not Where We Live

By • November 7, 2013 0 1530

“This Town,” subtitled “Two Parties and a Funeral—Plus Plenty of Valet Parking!—in America’s Gilded Capital,” is a book about Washington, D.C., by Mark Leibovich, chief national correspondent for the New York Times Magazine.

It’s not necessarily about where you and I live, nor is it about neighborhoods, Vincent Gray, Jack Evans or even Marion Barry, nor is it about Jim Vance or Doreen Genzler or Mark Plotkin, or even Bryce Harper or RGIII, or the Ambassador from Mexico, or the Whitman Walker Clinic or Arena Stage. It’s not about Adams Morgan, or even Georgetown, although Georgetown parties, and social and political folks make appearances, along with some restaurants and hostesses, but not the pandas at the zoo, although there are times when “This Time” resembles a zoo.

It’s not about this town, but about “This Town,” the one that seems to exist a little like the town under the dome in the TV show, whose citizens have been rendered invisible to the rest of the country.

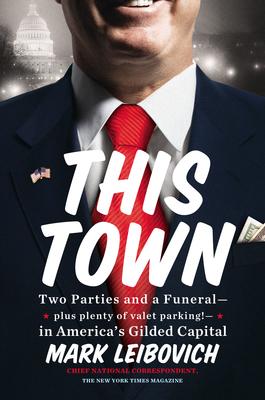

Never have you seen a book which has managed to put so much truth in advertising on its outside front and back covers. The front cover of “This Town” (published by blue rider press—their lower case, not mine), has a high-contrast, half-head, color portrait of what is clearly a denizen of This Town, a politician/lobbyist, easily identified as such by his red tie, half a big smile, dark suit, double-flag pin on one lapel, a thousand-dollar bill in his left pocket. The Capitol dome and muted night-time noir lights are behind him.

The back cover, illustrated by Ben Franklins floating from top to bottom, features a mission statement and a warning: “Today’s insider Washington has become a sprawling ‘conversation’ in which tens of thousands partake by tweet, blog, or whatever…The Washington story has become something more momentous, benefitting a ‘narrative’: a pumped-up word in a pumped-up place where everything is changing, maybe more than in any city in the country …or maybe nothing is changing at all, and the only certainty is that the city fathers of This Town will endure like perennials in a well-tended cemetery.”

Here’s the warning: “ ‘This Town’ does not contain an index. Those players wishing to know how they came out will need to read the book.”

Fair enough. I read the book all the way through, not surprised not to find my name in it, or that of many of my friends, associates and neighbors. Not surprisingly, since I work for this newspaper in a number of capacities, there were quite a few persons in the book whom I actually knew, or had seen in passing, or occupied the same room with (the Kennedy Center Opera House is a really big place), or had words with, or, or seen at a party or reception, on occasion, interviewed, or had seen on television. Memory in “This Town” plays tricks—one minute you’re absolutely positive you saw that Nixon-era attorney general walking his dog in Georgetown, the next time he’s in a Watergate documentary.

For the record, I have never met or talked with Mark Leibovitch, although I do read the New York Times Magazine occasionally, and the Washington Post every day (still), a paper for which he also worked. Leibovitch is not much interested in ancient John Mitchell-like history—he’s interested in now, right now, or how we got to right now. He is, it should be added, a terrific writer and reporter—his observations are sharp, funny, even touching, as he rolls out his characters, his scenes of parties and funerals (as well as political parties from Dems to GOP to Tea).

This is “This Town” that all the persons who’ve only visited here in horrible summers like this one complain about—this is Oedipus town, where incest of a non-physical kind is practiced as routinely as a Friday night poker game with beer and pizza is at a street corner or your friend’s house. One of Leibovitch’s principal revelations—that “This Town” rolls—like many towns only more so—on money is a theme, if not a shock. He documents, with style and even with some affection–the well-traveled journey—from Lott to Dodd and congressmen and senators in between—from holding office and public service to your friendly neighborhood lobby shop. Most politicians roll into town after having vowed to throw out the scoundrels (lobbyists and other hangers-on, some of them now strategists and consultants). It would appear that while assailing the Washington scoundrels and money men, they kept their business cards.

That part is hardly a revelation—it’s the merry-go-around of power types that includes members of the media, elected officials, their aides and chiefs of staff, the new media class of bloggers, twitterers, websites and Politico that is in some way as awe-inspiring as a second-tier royal wedding. Everyone—it seems—in “This Town” not only knows, works with at some time or another, socializes with, parties with and writes and blogs about each other, they’re practically sharing pads. Or as reporter noted—in a collection of comments from reporters who were mentioned in this book—if things got any more incestuous, their children would start having birth defects.

Leibovitch goes back to this theme—senators get elected, leave office and join a lobbying firm after vowing not to ever, ever do that, media types get tips from political aides wanting to get famous and so on time and time again. But in between, he offers choice vignettes and portraits—the scene at Ted Kennedy’s funeral, or the Kennedy Center memorial for “Meet the Press” wonder Tim Russert whom Leibovitch names the mayor of “This Town.” Russert’s shocking death and the service gives a graphic, at times moving, at times bewildering and head-scratching example of what happens when the citizens of this town gather to mourn—and kibitz.

The author gives a spot-on and up-to-the-second portrait of the new media as personified by Mike Allen and Politico — and especially Allen’s dot-dot daily reporting, in which he manages to capture the next second while pitching birthday, wedding, promotion and baby congrats.

The book is immensely readable. It’s gossipy, sure, but it’s also, one assumes, accurate in its snapshots of people. This is inside under the dome stuff, the parties—most of them seemingly thrown by the uber-hostess Tammy Haddad, whose brunches and parties during the week of the White House Correspondents Association Dinner is the top ticket in town.

When he’s not pursuing the career curves of politicians pursuing jobs, Leibovitch gives us some magnetic portraits of the likes of Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid and Sen. Tom Coburn, R-Okla., not usually seen in a non-partisan way.

In one chapter—dubbed “Suck Up City”—we see that the insiders may be competing, fighting, sniping and so on in a kind of rubber knife combat, but they’re always striving, branding and, well, sucking up.

Leibovitch’s portraits in “This Town” are hardly flattering. He may have some concerns about backlash, socially and accessibility-wise, but we doubt it. As he admits he’s very much an insider reporting on insiders, but it’s not like he’s Truman Capote. While a lot of what he serves up surprises—some of us actually don’t know that the Clintons and the late Tim Russert despised each other. Taken as a whole, however, the existence of “This Town” hardly surprises.

Everyone who lives here long enough, even on the periphery, experiences the little neighborhoods of “This Town”, those little drug-like rushes of being in the presence of power or name-droppers. But Leibovitch, on the whole, ignores the whole town in which “This Town” exists, except for a quick and undeservingly tiny passing reference. There is, after all, a context to “This Town”.

Fittingly, the book is pretty up to the moment, and moves fast like the kind of mystery thriller that I like to read. But we—and he—know the ending already. It’s going happen in 60 seconds, in Allen’s next Playbook which is appearing: right now in “This Town.”