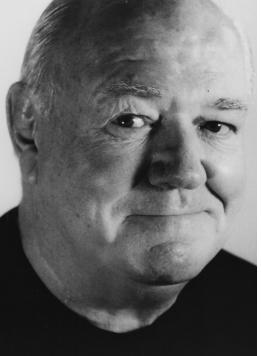

Tom Quinn: Himself, a Full Measure of a Man

By • February 3, 2014 0 1588

There are hundreds, probably thousands of Tom Quinns listed in phone books, on the Internet, on LinkedIn and Facebook—doctors, lawyers, businessmen, teachers, heads of institutions, an assistant coach for the New York Giants, a well known lobbyist here in D.C., a man studying structure formation in the universe.

You could go on and on.

The Tom Quinn I knew with the apparently common name of Tom Quinn was by many and all accounts an uncommon man, a one-of-a-kinder, a gem of a man who in his life was many things, played many roles, accomplished much. The Tom Quinn I knew passed away of complications from diabetes in New Jersey at the age of 79.

By the time I met Quinn, he was in his fifties. He had already been a championship boxer at Georgetown University, where he is the member of the G.U. Athletic Hall of Fame. He had been a memer of the U.S. Marine Corps, a time and position he valued with all the pride that a “simper fi” marine and Irishman can muster. He had been a political consultant, a stock broker and a National Football League investment advisor. When he lived in New York, he hung out with the likes of Norman Mailer, Pete Hamill and George Plimpton, literati of a particular pungent and vivid type. His travels with Mailer often took him to P.J. Clarke’s, a famed Manhattan watering hole, where he and Mailer often literally butted heads.

I wrote about him when he made another career change and lengthened his resume considerably. He had been taking acting classes at Georgetown University with Robert McNamara, then and now artistic director of the vagabond, eclectic and always surprising Scena Theater Company, where Romanian plays and the works of Beckett and the occasional classical Greeks and Wilde in the form of “Salome” were staples.

Quinn wanted to be on the stage, and I remember once McNamara telling me he was “a natural,” which in retrospect comes as no surprise. He was the kind of guy who acted through his pores, and he was that way in person. Most things he cared about, he felt passionately about. He was also a gentleman in the way that only the bleeding Irish can be—with Quinn it was deep breath time when you encountered him, as well as laugh-out-loud funny time.

Spending time with him could be exhausting. He was a natural story-teller, and it was Quinn who told me the origin of the tale surrounding Mailer’s novel, “Tough Guys Don’t Dance,” which also became a film. Quinn also happened to appear in one of Norman’s cutting-edge movies. When I wrote a feature story about Quinn, I got a note from Mailer’s office, words to the effect that Quinn was a fine, authentic and honest actor, a kindness not usually associated with the larger-than-life writer.

The honest part was also accurate: I would see Quinn start his career in Scena plays, one – acts by Havel or perhaps Beckett, and early in the time. Quinn would initially turn beet red at the start of a play, he practically glowed in the dark, and because in the early days the spaces were small, almost black box small, the sight was impressive.

But here’s what I remember and will always remember—in a very strange and moving play, “The Last of the Formicans,” at Woolly Mammoth. Quinn played a man who had been an architect and engineer all of his life, who knew how things worked and could read schematic plans easily. The man was suffering from onset of Alzheimer’s. There is a scene where he and his wife get up to leave and go home from a family dinner and he stands there in front of a door, unable to figure out how to use a door knob. The scene—there are no words that I recall—involved just the growingly bewildered face, the long stare at the door knob, something devastating going on. I cannot imagine anybody else doing this just the way Tom did.

Molly Smith cast him as a boxing manager in “The Great White Hope” at Arena Stage. He got into movies—a baseball manager in “Major League,” a boxing manager again, a wonderful small role in “The Pelican Brief” and other films. He did Shakespeare. He was always—as in his life—honest and authentic.

Not every one loves boxing, but Quinn understood it. He called boxing “advanced Irish pilots.” He was teaching boxing at Georgetown University’s Yates Field House to both men and women. According to his obituary in the Washington Post, he said that boxing “is the sport that every other sport aspires to be—two people trying to find out which is better and also learning something about themselves.”

“A fine gentleman,” one Irish bartender I knew said. “Very entertaining.” McNamara send out an e-mail about his death: “Another good Irishman gone.” But not so far away that you could forget him.