‘Report to the Academy’: Far Beyond ‘The Planets of the Apes’

By • July 17, 2014 0 1256

One of the great joys of the Capital Fringe Festival is that a theatergoer—avid, serious or just tasting—is sure to encounter an experience of the kind that they won’t get anywhere else. Given the volume of theater groups, shows and performers, this is not a guarantee or promise of quality or excellence, which is something that reveals itself in the performance, but it is a promise of things different and new.

Something similar has always been at work in any production put out there by Scena Theater for over two decades under its artistic director and founder Robert McNamara at venues throughout the D.C. area, operating as a kind of one-theater, mini-fringe outfit over time. Eastern European plays, the classics back to Greece, explorations of dada, Fassbinder, modern Irish playwrights, short plays by the avant garde giants like Beckett, Genet and Ionesco, there was always something that was new and refreshing, and often never seen before on Washington stages.

I cannot be entirely sure about this, but one thing you rarely saw in any of McNamara’s and Scena’s productions was McNamara himself, even though he is a veteran and experience actor. By way of the Fringe Festival, now we get a chance to see McNamara the actor in a production that seems to be the very essence of what McNamara and Scena, and by extension, the Fringe is all about.

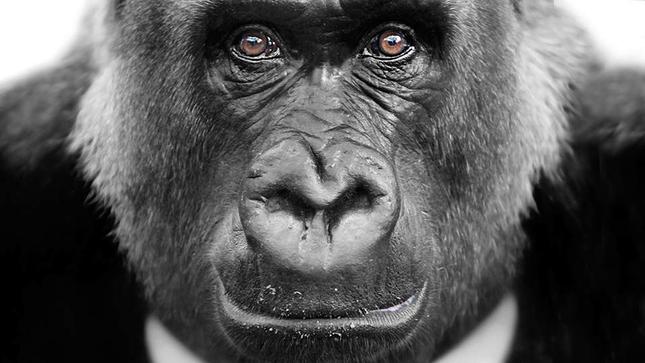

In “Report to the Academy,” McNamara portrays Red Peter, an ape who has seemingly buried his ape self in order to survive in the human world, and who’s now reporting on his life as a quasi-human to an audience of academics, and ourselves. It’s based on a story by Franz Kafka—the great novelist and short story writer from Prague who write terrifying stories in German about issues of identity in modern society. Gabriele Jakobi, who directed Brecht’s “Mother Courage and her Children” at Scena,” directs “Report to the Academy,” which is being performed at the edgy Caos on F gallery.

Red Peter may be an ape, but don’t confuse “Report to the Academy” with the serendipitous arrival of “Dawn of the Planet of the Apes” in your local cineplexes. Red Peter is no Caesar. He’s a being trapped between two worlds, trying to understand himself and the world he lives in. McNamara arrives on stage almost in a limping dance, carrying a tightly-wound cane, he looks on first sight like a slightly tipsy, shaggy vaudeville trouper, or perhaps one of the tramps in “Waiting for Godot,” canvassing the audience with eyes that appear at turns curious, sly, contemplative, challenging.

What follows isn’t so much a report as a story, a contemplation of a journey, of becoming—almost—human, the process of transformation with losses and gains, gains and losses.

It’s a bravura performance by McNamara on a stage that has nothing but a table and a chair, a little lighting and a little day music. Red Peter isn’t bitter. He has obviously thought long and hard about his predicament, about human beings, himself as an ape, himself as a human. He recounts his capture and being shot: “I was hit twice, grazed on the cheek for which I bear a scar, and in the body, a more serious injury.” His dilemma became simple to him—he was being held in a cage, in which he could not sit, stand or lie down. “I had to find a way out , there was no way out, you could only squat,” he says, in dreamy words that seem part lecture, part a discussion of pain.

In order to be free, he understood that he had to abandon his apeness. “They plied with me liquor, “ he says. But he also got to interact with his captors, simple, sometimes brutal sailors by acting like them—drinking, shaking hands, and all that act entailed. “Humans seek freedom, total freedom, which is not natural, as experienced in nature,” he said. Whimsically, he recalls seeing trapeze artist flying true and through the air, being caught, flinging themselves into air. “It was an illusion of freedom.”

The ape, in the end, learns to speak—and in a very nuanced way, like a pedagogue who is also a poet. He launches on a career on the vaudeville stage, a successful one at that. In the process, he gives himself up, a kind of imposed cruelty. “It was either the stage or the zoo,” he explains.

As he tells his stories, you see a kind of self-awareness that is shockingly sad as well as funny. He cannot recall himself in the mirror. And McNamara gives himself little bits, like an actor, a vaudevillian, a song and dance man. His limp often changes, his gait has a foot dangling at times, at other times dancing, he slouches, stands tall, and occasionally, spurts of ape yips and laughter, desire and joy come out of him, as if escaping by memorized accident.

Many writers and observers see the story as a fable and parable about assimilation, which could certainly be true, given Kafka’s own issues about his identity (see also “Metamorphosis”). These days, with a heightened societal awareness of cruelty towards animals, that issue also pops up per force.

McNamara—in his studied, layered ways, his ticks and tricks, his intensity and his unstill ways—makes Red Peter someone, somebody, neither ape nor a man, but a living, thinking, speculative being with a searing soul.

“Report to an Academy” is at Caos on F July 15, 19, 25 and 27. Go to the Fringe Festival website for details at capitalfringe.org