Through Fire, the U.S. Emerged

By • August 22, 2014 0 1443

We are always tourists in our own cities. Everywhere we walk, bike, run, stop and go, every park bench we sit on a summer’s noontime, history beckons us. Often, we’ve stopped and peered through the black fence, watched and stared at the pristine white of the White House. Turn around and you see in Lafayette Square Andrew Jackson waving astride his horse, and around the corner, the U.S. Treasury building, stolid Alexander Hamilton in a starring sculpture role.

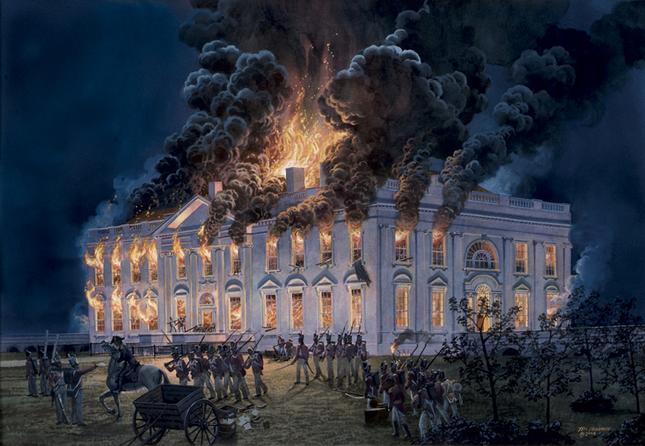

Two hundred years ago on a dark night of a hot August 24, the White House, then known as the President’s House, was on fire, as were pretty much all of the federal buildings of Washington. What was then an uncompleted, but nonetheless sumptuous U.S. Capitol housing the House of Representatives, the Senate, the Library of Congress and the Supreme Court was torched by a relatively small force of around 800 troops and sailors of His Majesty’s armed forces. Americans who had stayed behind were weeping. The residents of Tudor Place and Dumbarton House in upper Georgetown could see the flames clearly throughout the night and then the smoke the following morning. The U.S. Navy Yard, with ships, war materiel, ammunitions and canisters were also set to flame, this time by Americans trying to prevent the invading British from gaining control of weaponry.

President James Madison had already left the city, lest he be captured, but his wife Dolley, the indomitable hostess with the mostest of her day, was, according to the stories, busy saving the Gilbert Stuart portrait of George Washington from the rapa- cious British. This was without question the lowest point for the fledgling U.S. republic during the course of the War of 1812. The very survival of the nation appeared to be at stake. United States negotiators in the Belgian city of Ghent, who were looking for a peaceful settlement, appeared about to receive onerous terms from their British counterparts.

Yet only a few months later, the climax to the whole war brought different results than one might expect. In the end, the war was a draw, not a victory, although it gave off the flavor of triumph. For the United States, still united, the Treaty of Ghent ended a war that had begun as an outraged and almost foolish declaration against the Mother Country over impressments of American sailors and commerce and trade. But the ending felt triumphant. In the aftermath of the burning of Washington, which we commemorate if not celebrate this month, came the bombardment of Fort McHenry in Baltimore. It was resisted bravely and witnessed by an American named Francis Scott Key, who was inspired to write a poem which would eventually become our national anthem, “The Star Spangled Banner.” It was followed by an American victory at Plattsburgh and the prospect of better hopes. Even as the ink was drying on the treaty, U.S. General Andrew Jackson pulled off a scorching, impressive and devastat- ing victory over British regulars at the Battle of New Orleans, which gave us another hugely popular song by Johnny Horton but also restored American pride and confidence.

In terms of popular culture and national memory, the War of 1812 remains a peculiar, selective historic event, remembered differently by its participants: Canada, Great Britain, the United States, as well as various Native American tribes. For Canadians, who fought off (with the English and Indian tribes) what can only be called an inept and foolhardy invasion by the Americans, it is a rare and celebrated point of military pride. For the British, the war was something of a sideshow compared to the long and difficult war with Napoleon’s France, and was fought in the manner of teaching the breakaway cousins a lesson. For the United States, it became a transforming experience, full of drama and trauma. It was a war bitterly fought in the political arena, with a congress and country, equally divided for and against—westerners and southerners were for it, northerners, especially New Englanders, were against it.

You can practically smell the smoke and brimstone fire and hear the cannonades if you read the recent “Through the Perilous Fight” by Steve Vogel, a veteran Washington journalist on military matters. (He was part of a Pulitzer Prize-winning team of Washington Post reporters writing on Afghanistan). The book is a dramatic and evocative telling of six critical weeks of the War of 1812, beginning with events leading up to and surrounding the British invasion and burning of the capitol. There is also “The Burning of Washington, The British Invasion of 1814” (The Naval Institute Press, 1998) by Anthony Pitch, a veteran historian who has also given Smithsonian tours and walks on the subject.

Vogel’s book reminds us of two things: that war and history are always about people, and that however confusing, the issues of this war, which sprawled into Canada, the Great Lakes area, and was fought along and on familiar native rivers, villages, country sides, hills and forests and cities, proved to have far-reaching consequences. Vogel paints graphic pictures of the fighting and destruction, as well as portraits of the characters of its principal protagonists. On the English side are the three commanders, Admiral Alexander Cochran, who harbored an intense hatred against America, the flamboyant and mercurial rear Admiral Sir George Cockburn and the beloved and stoutly brave Irish-born Major General Robert Ross. Among the Americans, we see the Madisons, Mr. and Mrs. in action or inaction; James Monroe, then Secretary of State, in the middle of various military actions; Commander Joshua Barney, arguably the ablest and bravest of American military leaders on the scene; Brigadier General William Winder, who seems often clueless; and Paul Jennings, the young Madison family’s slave and retainer who helped rescue the Washington portrait and witnessed the burning of the White House.

Finally, and most full bodied, there is Georgetowner Francis Scott Key, whose presence touches on so many of the young country’s concerns but who became entirely unforgettable with his penning of a poem that became our national song. He was a father of 11 children, a devoted church goer, (at St. John’s in Georgetown, where he resided on M Street), a husband, a slave owner sympathetic to the plight of slaves, but a legalistic defender of the institution. His brother-in-law and great friend was Chief Justice Roger Taney who authored the Dred Scott Case. He is buried with his wife at Mt. Olivet Cemetery in Frederick, Md., where you can see the Confederate flag flying over the graves of Confederate soldiers. Key was asked to act as a negotiator for the release of an American prisoner and ended up having dinner with the two British admirals and General Ross, who was, a short while later, killed in a battle leading up to the siege of Fort McHenry. Key watched the bombardment, a hellish, non-stop affair, and “by dawn’s early light,” saw our flag was still there.

The poem became a song, became an anthem, became history, the song we sing at each and every sporting event. Can you imagine Francis Scott Key at Woodstock in 1969? But his song was there, played in singular fashion by revolutionary rock guitarist Jimi Hendrix. Washington in flames inflames us still. In some way it’s part of the dust of sidewalks and guided tours and the way we see history. After the war, America changed. It stopped being the creation of the founding fathers with Virginia presidents, and became something else and more, the Republic going westward democratically, making itself large and permanent. Ahead loomed the last challenge to its local validity, the Civil War, the last war to be fought on American soil. All that was burned was rebuilt and the country and city rose out of the ashes to become itself.