This Week: Injustice in Missouri, Emotion and ‘The Giver’

By • September 10, 2014 0 943

If you watch the news in this town and our towns across the country, you’re bound to have been saddened, bewildered and not a little agitated over the furor and fury that has erupted in Ferguson, Missouri, where an unarmed young black man was shot by a white police officer. This horrible, tragic event was followed by demonstrations, clashes between the police and demonstrators as well as looters, fire and tear gas in the night almost every night, in ways that we have seen before throughout our troubled and often violent racial history.

Nothing has really been settled yet. Ferguson, a suburb of St. Louis with a predominantly black population and an overwhelmingly white police force, remains a cauldron of outrage, uncertainty, seething and explosive emotions, and conflicting and confusing accounts of what actually happened. The local police—heavily armed with high tech, military-style weapons—along side the county police and the highway patrol, and soon to be joined by the National Guard—have repeatedly clashed with demonstrators, many of whom have protested with their arms held high in the traditional “don’t-shoot” stance. The FBI is investigating the shooting and everything surrounding it. A video showing of the shooting victim, Michael Brown, and a friend allegedly stealing boxes of cigars from a convenience star was released several days later by the Ferguson sheriff’s department to outrage in the community. There have been at least two autopsies done on Brown’s body. The officer who shot Brown has been identified. The parents of Brown are demanding the arrest of the officer.

Ferguson has become a flash point for anger, another reminder that the racial divide in America appears in this case as wide and deep as ever. The situation was not new. The volatility of relations between the police force and the residents of Ferguson bubbled over with the shooting, but it’s also a part of a process which we have seen locally when Prince Georges County became a majority black county, even as the police force remained predominantly white. The same was true for Washington, D.C., in the wake of the coming of home rule until Marion Barry became mayor.

The echo of some of the imagery we’ve seen—the protesters in the streets, the heavily armed police force, acting very much like a military force, and the presence of familiar civil rights leaders like the Rev. Al Sharpton, who said, “Ferguson is the defining moment today in America”—reminded people of other times and other places—the shooting of Trevon Martin and Selma, to some.

Ferguson was a news story that became something way beyond itself. It was a reference story to the ongoing, often violent saga of race relations in this country and delivered its quota of tragedy, metaphors and memories.

Other things happened, of course. Ukraine remained a tinderbox, deaths from Ebola remained on the rise in West Africa, the truce in Gaza appeared to be holding amid the ruins and great tension. The United States — in a limited, but effective, way — helped slow the momentum of ISIS in Iraq with fighter and drone attacks.

We caught up with an old movie, “Dead Poet’s Society,” Peter Weir’s elegiac, lovely piece about the price of non-conformity at a 1950s prep school, where actor Robin Williams presided over and inspired a group of young students with “Carpe Diem.” It was a quiet, touching movie, every bit as memorable as Williams’s more manic efforts or the creepy “One Hour Photo.” It was also emblematic of the gifts of Weir, who gave us “Witness” and “The Year of Living Dangerously.” Williams’s suicide Aug. 11 and its manner touched cinematic tribal memories for anyone who watched television, laughed out loud often or went to the movies. It became a loss, like that of some never-forgotten friend from a distant land.

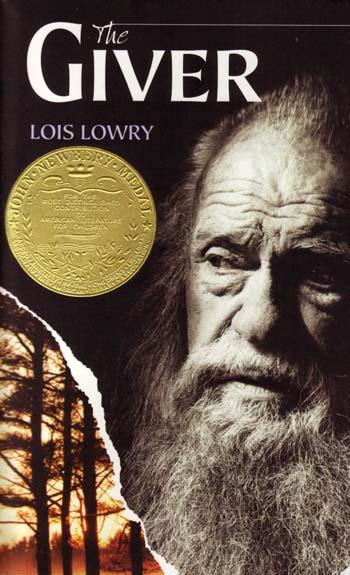

We also saw the new movie, based on a classic old tome of a novel: Lois Lowry’s 1993 novel for young people, “The Giver,” a book that found its way into many middle-school and high school curriculums as a thought-provoking work that let youngsters think about the kind of world which was best to live in.

Many years in the making—which, for what it was, did a respectable $12.8 million at the box office this weekend—it was an approximation of the book (which I gulped down over the weekend). It seemed almost hip and trendy in the sense that it caught the tail wind of two other movie version of teen books about heroes and heroines in a dystopian world, “The Hunger Games” and “Divergent,” helping to make the word “dystopian” very cool itself.

“The Giver”—which was helped into existence by the persistence of actor Jeff Bridges who has the title role—is about a world and a society, which has survived an unexplained catastrophe, called the ruins. In this brave new world, there are no emotions. There is nothing called death except the euphemistic “release” of the elderly and rule breakers. There is no music, no colors and no books. There is no conflict, racial or otherwise. There’s no unemployment, no war, no starvation, no unnecessary excitement, no love or hate. It’s all controlled by a ruling class, called the elders, and every one in it knows their place.

There is also the giver, the one person who holds all the memories of events, feelings, feelings, creativity and such that existed. He is there as a kind of wise man in waiting, who has the answers for any questions that might come up. In this society, everyone is given an assignment—and young Jonas, age 16 (he’s 12 in the book), is about to get his. He will become the new giver, a process by which the Giver himself fills him with all the memories that he has inside him.

Jonas soon s finds himself in conflict with the “community,” his family and his friends, not to mention a watchful head elder, played by Meryl Streep in the film.

This is, of course, a movie and it must have its heroics and action, but it is also a highly affecting work. I’m not sure why but the daily lives of Jonas, his family and friends and his adventures are a potent emotional brew.

We left the theater in Georgetown and wandered by the water fountain at Percy Plaza in Georgetown Waterfront Park, past the new restaurants at Washington Harbour. We saw the birds of the river and the family of man, chaotic, warm, energetic, enjoy the day and seizing it for its quality of gentleness and sunshine, the citizens of this town and our town, enjoying the fruits of whatever labor there is. I would not have been surprised to see a spry Walt Whitman singing the multitudes.

There were as yet no signs of ruins, only a pirate ship and two impressively sized yachts and dogs at play—these everyday things, far from Ferguson for now.