A groundbreaking era in the history of human innovation, the decades surrounding the turn of the 20th century were marked by the achievements of Thomas Edison and Henry Ford, along with medical breakthroughs from insulin and cardiology to blood transfusions and x-rays.

As a natural response to the rapid development of science and technology, the arena of fine art underwent many distinct mutations toward the end of the 19th century. The most clear and immediate of these was the advancement of photography, which made owning and taking photographs available to a broad audience of artists and visual thinkers.

Photography opened the door to an entirely new understanding of composition, value and spatial relationships, re-energizing artists’ methods and creative visions. However, with the ability of the photograph to capture the existing world, painting and drawing were left to find a new direction of visual communication.

“A Subtle Beauty: Platinum Photographs from the Collection,” an exhibition on view at the National Gallery of Art closing Jan. 4, gives visitors a close look at some of the finest photographic images from the turn of the century.

Revered for their luminous, textured surfaces, from a velvety matte to a lustrous sheen, platinum prints played an important role in establishing photography as a fine art.

The photographs are also prized for their extraordinary tonal range: from creamy shades of white to delicate gray midtones and from warm, sepia browns to the deepest blacks. These qualities made platinum prints a preferred choice among the pictorialists, an international group of turn-of-the-century photographers who championed the medium as a means for artistic expression.

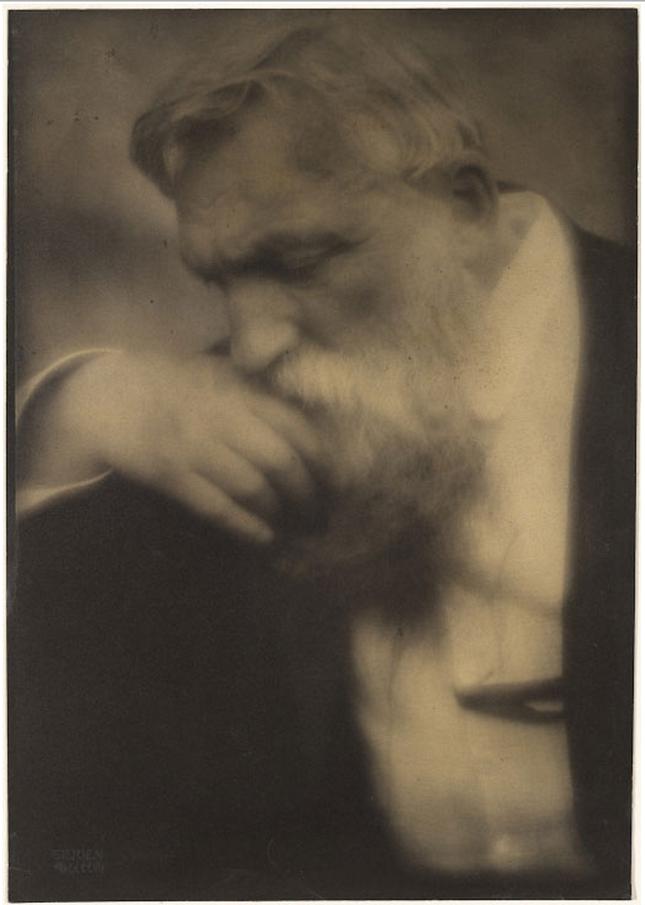

There is something of a 19th-century romanticism about many of the photographs – particularly the portraits – which makes the occasional drama of a subject’s pose seem perhaps silly to the contemporary viewer. But at their best, they capture an almost literary transience, with the subject’s eyes imparting a depth of intellect and emotion in the moment that it is materializing. Heinrich Kühn’s portrait of his brother Walther (1911) has this tremendous affect, as does Alfred Stieglitz’s mesmerizing and balanced portrait of his elevator operator, Hodge Kirnon (1917).

The effects of those portraits are brought together with a hallowed, atmospheric brilliance in Edward Steichen’s portrait of August Rodin (1907), positioned in a contemplative pose reminiscent of the sculptor’s most recognized work, “The Thinker.” Perhaps given the famous subject, the portrait takes on a decidedly eternal quality, which was probably not mere chance.

Maybe the most beautiful photograph in this intimate exhibition is Frederick H. Evans’s “York Minster” (1902). Evans captured without equal the cavernous, grand and reverberating awe of a cathedral. The way the soft light washes over the relief ornament and suspends itself palpably in the vaulted space between the high windows and the crowns of the arches is a true source of bleary-eyed, skip-a-heartbeat beauty.