Man Ray at the Phillips: Surrealism and My Discontent

By • February 16, 2015 0 3874

I need to get something off my chest. Surrealism annoys me a little.

It always feels like a cultish charade of midcentury intellectuals: the aggressive anti-rationalism, the unnecessary visual lexicons of the pseudo-Freudian subconscious, the exploration of the mind’s mysterious fissures, the creation of new realities that defy constraints of earthly existence…it’s all just a little much for me. I find its sensibilities much better fitted to a Loony Tunes parody than a deadly serious museum wall (for a good time, Google “Porky in Wackyland,” 1938).

This is not to say Surrealism never had its time or place. An evolutionary offshoot of the Dada movement, it was born in France as a retaliation against the societal trauma caused by World War I. All across Europe cities were leveled, communities were displaced and national currencies were tanked by hyperinflation. A flu epidemic had wiped out nearly six percent of the world, and a generation of European men were lost to the trenches.

The world was no longer rational, so writers and artists determined to dig beyond their rational intellect to decipher it – perhaps in search of deeper meaning, but likely as much an act of defiance and self-preservation. Surrealism was founded in 1924 by the French writer André Breton. He defined it as “Psychic automatism in its pure state, by which one proposes to express…the actual functioning of thought.”

Whatever that’s supposed to mean.

Surrealism rapidly caught on across Europe, and the outset of World War II found many of its leaders taking refuge in New York City. The wide exposure of their work to American artists was one of the major catalysts in New York’s later development as the epicenter of postwar art and culture.

Though Surrealism broadened the boundaries of art profoundly, its arcane ideologies and strange elitism rendered the movement insular and prohibitive – a perception that fine art has never really overcome, and now seems largely to have embraced. (Such vainglorious and esoteric practices arguably foreshadowed the profligate economic culture of today’s contemporary art market.) Furthermore, its initial nobility of concept gave way to a hackneyed commercialism by second-rate imitators.

All of this, oddly enough, is to say that I had a damn good time at the Phillips Collection’s latest exhibition, “Man Ray – Human Equations: A Journey from Mathematics to Shakespeare,” on view through May 10.

I experienced frustration, complexity, humor, disappointment, apathy, interest, excitement and occasional moments of great beauty; perhaps not dissimilar from a given day inside my head. From the standpoint of Surrealism, this is a smashing success. My fundamental conflicts with the subject matter never waned, but I walked away with renewed – if weary – reverence for the accomplishments of Surrealism, and particularly those of Man Ray, the only true American Surrealist.

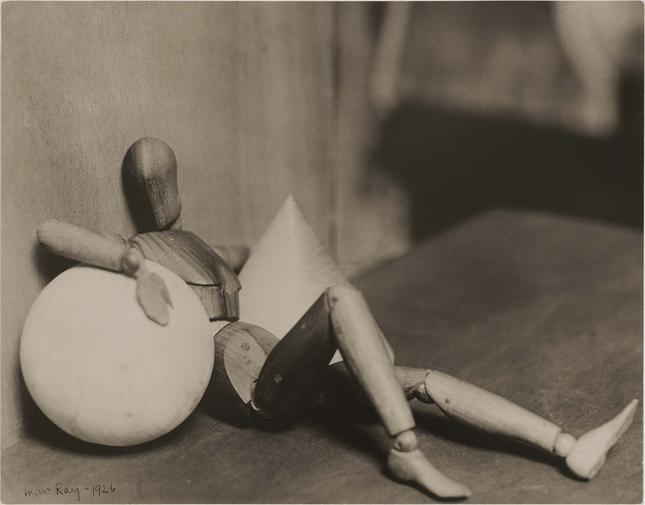

Working in Hollywood in the late 1940s, Man Ray (1890-1976) created a series of paintings called the “Shakespearean Equations,” which he considered his defining creative vision. They were inspired by a series of photographs he had taken a decade earlier of 19th-century mathematical models and sculptures. The Phillips exhibition displays the paintings, photographs and models together for the first time in history, along with other paintings, photographs and assemblages by the artist.

The show illustrates Ray’s conceptual fixation with human/object interrelation: making people that look like things and things that look like people. In many ways it shows how Surrealism has affected our visual notions of the subconscious as much as the subconscious has affected notions of Surrealism.

For all his clear ambition, Man Ray was not a great painter. Unlike Dalí, Giorgio de Chirico or Max Ernst, whose eyes for phantasmagoria were on par with their painterly finesse, Ray’s canvases are tedious and inexpertly rendered. However, his photographs are stark, lucid and remarkable. They hold their own against the best Surrealist work, as well as any photography from this era.

In Ray’s photographs, the complex intermingling of object and anatomy, light and shadow, atmosphere and geometry get distorted both physically and emotionally. For instance, in two corresponding plates we see the formal juxtaposition of a peach and a deceivingly racy perspective of a woman’s bum, hands and toes. The illusion is so effective that it takes a moment to understand what we are even staring at.

In his famous “Le Violon d’Ingres,” a model’s body transforms into a violin, inspired by Ingres’s Neoclassical paintings “Valpinçon Bather” and “Le Bain turc.” It’s impossible not to appreciate the whimsy.

To a lesser extent, Ray’s models are clever, but they feel like carnival games: charming, enjoyable, but of little consequence. Ironically, what are always more impressive are his photographs of these models.

A great demonstration of this point is the series of “Non-Euclidean Objects” in the corner of the fourth gallery. There is the model itself, a geometric soccer ball of sorts. Then there is a photograph of the object, and a drawing of the object. Even with the object directly before us, its photograph, hanging on the wall behind it, is far more powerful. The way Ray manipulates the gradual value of shadows against the shifting planes of the object’s surface is stunning. He makes the photograph express what reality does not. And I don’t even remember what the drawing looks like.

Black-and-white photography was Ray’s greatest achievement; he saw something truly original through the lens of his camera. Using shadows and light, he made images of mundane objects that maintain their essence but exist simultaneously as beautiful earthly abstraction. His silver prints of an egg beater and photographic equipment are notably exceptional.

But this is never clearer than in the final gallery, with the “Shakespearean Equations.” (As a point of interest and debate, the arrogance of which I earlier accused the surrealist movement is on full display in the very title of this series, as the exhibit text admits Ray chose it for no particular reason. He just seems to have liked it—and it also happens to be preposterously smug.)

Each of the paintings try to wring out its nebulous intrigue like water from a vaguely damp cloth. Meanwhile, the objects on display are interesting to admire in the same way as a Tim Burton movie miniature might be; their intricacies and sheer existence are strange and lovely, if not achieving quite the force of a true sculpture.

Then there are the photos of the models, which transcend the objects themselves. All sense of scale, proportion and space are elevated; Ray’s use of composition culls an emotive visual vocabulary of the grandest Roman architecture. They are disconcertingly anthropomorphic, too, drawing us in and pulling us out through their undulating rhythms of shadows and light.

The photographs discover an internal logic all their own that never betrays a haunting essence of the unknowable. Looking at them, we don’t even have to try – they take us ever so naturally along for the ride.

At its best, this is what the art of Surrealism can do: capture our minds and usher us into its alternate reality. Here, we exist momentarily in a world we can never truly enter, for it survives like a flickering candle in the dark recesses of our minds.

“Many Ray—Human Equations” is on view through May 10. For more information visit www.PhillipsCollection.org