A Haunting, Harrowing ‘Dialogue of the Carmelites’ at WNO

By • March 5, 2015 0 1133

To say the least, “Dialogues of the Carmelites”, now receiving a haunting, sometimes harrowing Washington National Opera production at the Kennedy Center’s Opera House, is not what you’d expect from an opera, even in today’s music climate, where so-called contemporary operas are starting to appear regularly on season schedules.

“Carmelites” is a 1957 opera written by Francis Poulenc, a French composer who was known for his song cycles and music that straddled the lines between the sensual and spiritual. Yet, he composed an opera that’s managed to become a contemporary classic, a historical opera that today reminds us of contemporary horrors.

In the hands of a fine cast, a patient and imaginative director, driven and decorated by impeccable stagecraft, the WNO production manages to overcome what seem to be some minefields in the music and the structure of the opera itself.

“Carmelites,” which elevates musically a historic atrocity that was a by-product of the French Revolution run rampant, was sung in English, per Poulet’s long-standing request that the opera would be sung in the native language of the country where it is performed.

Musically, as an opera, the structure avoids the familiar—the highlights are strong dramatic duets between several principal characters, rising, graceful harmonies most effective with the use of a cappella singing from nuns gathering together. There are no arias, no overt expressions or opportunities for grandiose displays of technical skills, but there is music, sometimes emphatic and overly dramatic, that signals emotional surges and passages. The idea in fact was born as a film script, and the music often operates like a film score in the sense that it acts as a guide for the audience’s emotions.

The Carmelites were a group of nuns living in a convent in Paris, often used by aristocrats or good families to deposit daughters with emotional problems, as is the case here with the character of Blanche, a nervous, even fearful, pretty young woman who’s elected to come to convent. She’s come at a time of sea change both in the convent and the country. The prioress, Madame de Croissy, is mortally ill and so is France, beset by the bitterest of outrages at the revolution, best by mobs intent on destroying churches, monasteries, convents and anything that smacked of the Catholic clergy.

It’s a feverish, fearful atmosphere, more so after the prioress, raging against God, furious at her suffering, dies, and is replaced by the calm, pragmatic Madame Lidoine. She is placed in charge of a convent full of fear but also with a surge of longing for martyrdom. She’s resistant to the idea—even though their priest comes to hide and warn them of the danger.

In the end, after their arrest, she embraces what is a given prospect; they’re sentenced to death for “gathering in a group”, and all manner of crimes dreamed up by a feverish mob.

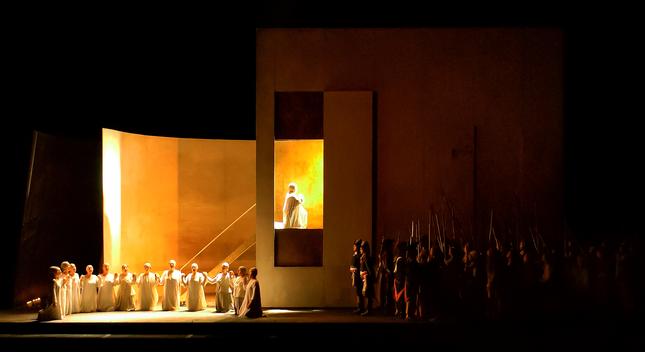

The steady, relentless march of the Carmelites toward their fate is conducted in an atmosphere and setting that’s almost feverish. The set by Hildegard Bechtler is a massive, gleaming structure that often dwarfs the nuns who seem to gather strength coming together in groups. Here, in the lighting work by Mark McCullough, shadows surge over the surface, large and small, elliptical and strange, flickering and moving figures against candlelight and mirrors.

In this environment, emotions rise almost naturally. Not only is Blanche burning with fear, but also the audience starts to feel a growing dread as the inevitable outcome approaches.

You have to feel and fear for the characters and in this, the production is served well by the cast—mezzo soprano Dolora Zajick commands the stage from her cot as the dying prioress; rising star soprano Leah Crocetto’s singing is full of clarity with a strong voice that cements leadership qualities—including unto death—of Madame Lidoit. Another new star, Layla Claire plays Blanche with tremulous fragility. She’s like a changeling lost in the forest. Ashley Emerson as Constance seems almost like a too-wise and eager mascot for the group.

WNO Artistic Director Francesca Zambello’s guides the production by letting it evolve almost organically—as the pace leads the women more and more into the maws of the revolution, they seem to come together as a group—you see them praying lying flat on the ground, coming together in prayer, in debate, in sorrow and fearfulness, and finally, to their end.

The ending is a remarkable piece of stagecraft that would punch and peel the hardest heart—all the nuns, facing the mob, climbing one by one to the platform, singing and chanting hymns, each with a different way of walking, toward the guillotine. The singing is interrupted only by a resounding and sharp thud and all the while the singing continues as their numbers dwindle.

At this point, the proceedings become unforgettable. It seems almost as if, as they all disappear, that the singing is louder and deeper, an illusion of the heart.

(“Dialogues of the Carmelites will be performed again on February 27, and March 5, 8 and 10)