Norman Lear and His Art: Even This We Got to Experience

By • April 13, 2015 0 1308

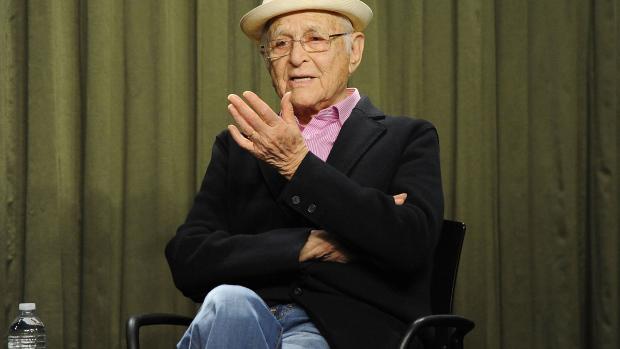

This week, a spry 92-year-old guy showed up at the Kennedy Center to give a lecture.

Close to thousands stood up and cheered.

As the man said, “Even this he got to experience.”

The man was Norman Lear, who in a long and productive life, gave us Archie Bunker, Meathead, Edith and the Jeffersons and Sanford and Son, “Good Times” and even “Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman” and with those shows and those characters left an indelible mark on the hearts and mind of what you might call the regular folks of America.

Lear gave the 28th Annual Nancy Hanks Lecture on Arts and Policy March 23, as a sort of pep talk to Arts Advocacy Day the following day on Capitol Hill. And what a whoop-dee-doo night it was. Folks nearly filled up the Concert Hall at the Kennedy Center and got a time well spent, for free.

Lear was there to give a life-and-times tall-tale sounding talk on a day that saw Republican Ted Cruz, the darling of the right and of the religious right, which fittingly is an old bête noir of Norman Lear’s, announce his presidential run. There also was the 107-member Atlanta Symphony Youth Orchestra and the Voices of Inspiration for musical inspiration.

Not only that but there was the uncommon man of the moment: Common, actor, composer, hip hop star, children’s book author and Oscar and Golden Globe winner for original song (with John Legend) for “Glory” in the film “Selma.”

Common noted that it was Lear shows like “Good Times,” “The Jeffersons,” “All in the Family” and “Sanford and Son” that allowed him to see himself and his people portrayed as part of the American cultural tapestry in a way that he could relate.

Lear’s memoir, “Even This I Get to Experience,” figured strongly and often in his talk,which was a riff on his life, and meaning, with asides to the importance of the arts in American life, especially in theses troubling times in which the arts, paradoxically, seem to be at once available in abundance in its delivery by new technology, but in danger of being robbed of their importance and stifled by that same technology.

Lear walked onto the stage—not a very long journey—and received thunderous applause. Lear showed he still knew his way around a set up and a punch line: “See, if I were 88 or something like that, why I’d still get applause, sure, but now that I’m in my nineties I cross a room and I get an ovation.”

He was more than just being here—he had some things on his mind, and dealt with them with banter, comedic fury, a little anger, dispensing wisdom after having received it.

He talked about his father, who ended up in prison during the depression, and about being left in the care of so-called uncles. “They weren’t real uncles, and it wasn’t such a good thing. One of my relatives placed his hands on my shoulders, looked deep into the tear-filled eyes of a nine-year-old and announced with a smarmy solemnity, ‘Remember Norman, you’re the man of the house now.’ ”

“That’s when my awareness of the foolishness of the human condition was born,” he said.

He remembered when he breathlessly told his mom that he had been inducted into the Television Academy of Arts and Science—alongside David Sarnoff, Bill Paley, Edward R. Murrow and Paddy Chayevsky. “My mother’s reaction was typically unforgettable. ‘Listen,’ she said. ‘If that’s what they want to do, who am I to say?’ ”

He’s a man who knows how to laugh at human foibles, including his own. “I blew my fortune investing in businesses, which I knew nothing about, to the point I might have had to sell my house. I’d made plans to be cremated on my death, but my son-in-law talked me out of it. He said I want to take your grand-children to a gravestone that reads, ‘Even this I get to experience.’ ”

Lear took stock of the world, by reciting climate change, income equality, ISIS, and most damning for the arts, a dwindling lack of support not only from government, but from the populace. And yet, he remains steadfast to the importance of art.

“Despite everything I see and feel, however, I don’t want to wake up the morning I am without hope,” Lear said. “We will save the world.” He called the arts one of the things that brings us together, which cause us to see and hear as one. “We are then free to delight in or disparage according to our individual tastes, but in the embrace of art and beauty, still one.”

He decried a culture that was numbers driven, spiritually sterile, dominated not by exploration or art but by consumerism.

“Republicans never mention Eisenhower anymore,” Lear said. “He warned us about the military-industrial complex, to which he had wanted to add congressional.”

Lear was often accused of editorializing in his shows. To this accusation, he replied, “I realized I was a man in my fifties then. So, why shouldn’t I have a point of view?”

It was more than that—in a television world dominated by sitcoms from the 1950s like “Leave it To Beaver” or, worse, “The Beverly Hillbillies,” Lear’s “All in the Family” and all the rest stood out for their freshness, their authenticity about working class and middle class America and their empathy. He imagined his way into the lives of others to the point that years later, someone like Common and hip hop artists praised him for seeing their lives.

That’s an unforgettable achievement. When he was honored by the hip-hop community for the impact of his shows, he got an answer to what he called the basic question: “What do a 92-year-old Jew and the world of hip hop have in common?”

A lot, as it turns out.

“It has taken a lifetime to understand the importance of the audience as well as the performers,” Lear said. “It has taken me 92 years, eight months and a day to get there tonight to tell you that. On the other hand, it has taken every minute, every split second of each of your lives to come to the Kennedy Center to spend this time with me tonight. “

“Add it up. I win. And even this I get to experience.”