Our ideas of folk art are strangely and inherently conflicting. By nature, American folk art is that made by people who, through means of economy, location and a number of imposing and typically limiting factors of their lives, have managed to avoid contamination by the otherwise universally epidemic tradition of the Western canon.

Over the past century, these have almost invariably been black Americans living in small, rural isolation. Their art is intrinsic, pure, seemingly born from some chaste and chasmic human urge to create and communicate through ritualistic vessels. There is a fascinating and undeniably refreshing sparkle to this work, both alien and deeply familiar, which deciphers what we already know through wholly unique lenses.

Our rote and stressful world is born anew, like hearing a mundane story told by a child who must stretch the boundaries of their limited logic and experience to piece together their understanding of how things work. (In one great example, a little girl who just took off on her first plane ride turns to the man sitting beside her and asks, “When do we get smaller?”)

The way folk artists interpret people, architecture, nature, composition, is unaffected by the infinite textbook methodologies of these principles, as typically applied in contemporary practice. There is a defiant quality – however unintentional on the part of these artists – in simply proving that one can reflect on the world around them through art without any of the pseudo-philosophical toolkits and mechanisms the rest of us cling to like lifeboats.

I was taught to stand before “R. Mutt” with the sober reverence and resolute awe of the direly religious before the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. And I do just that. Now, that does not mean I’ve ever given time to actually face the question of why I do that. (Maybe I should, but that’s another issue altogether.) In the “art world” we all love to scoff at, the “Emperor is naked” fable ends not with throngs of disabused and enlightened townsfolk, but with a bunch of very smart, slightly bored aristocrats telling you to shut up and play along.

But can I observe folk art with an even-handed deference, without some degree of bemused condescension? More important, is it even possible for me to accept it on its own terms? The problem is this: as soon as this work and these artists are subjected to our reliable systems of cultural governance, they become permanently and inalterably defiled. To expose these artists to the public – and worse, to the relentless burrowing scrutiny of scholarly excavation – is to uproot and plow over the wild, billowing prairie grasses of their creative vantage. Once they are introduced to this new environment, their amplified professional awareness obliterates the rustic immaculacy of their id.

Think of it another way: When Europeans introduced rifles to Native Americans, they could not conceivably avoid using this tool and the advancements it afforded them. Or perhaps more appropriately, once we introduced them to our germs and diseases, there was no way they would not get sick.

This delicate navigation is a systemic concern of anthropological efforts today. How can we preserve the purity of small native cultures while also allowing observational access to the curious colossus of global society? In the arena of American folk art, the discovery of a small subset of self-taught, southern black artists from Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama and Georgia was a remarkable phenomenon in the 1970s. In 1982, here in Washington, the Corcoran Gallery of Art presented “Black Folk Art in America: 1930 –1980,” the first exhibition and publication documenting these previously unknown artists like Sister Gertrude Morgan, David Butler, Bill Traylor and William Edmundson (all of them worth poking around for online).

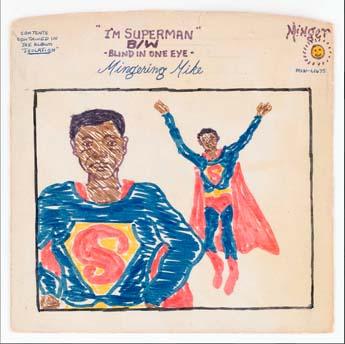

And then we have the crazy magic of Mingering Mike, whose exhibit and catalog at the Smithsonian American Art Museum is wondrous, unprecedented and seems to occupy an almost unimaginable crossroads in American art: both deeply resonant within the unmediated freeform heritage of folk art, and rooted entirely in popular culture. It brings together both sides of these hitherto mutually exclusive worlds, like a native flower long thought extinct found blooming in the cankered brickwork of a downtown alleyway.

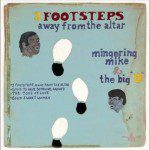

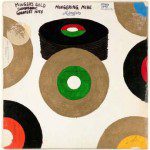

The story starts with Dori Hada – a local DJ by night, a criminal investigator by day – who was digging through crates of records at a D.C. flea market. There he unknowingly stumbled into the elaborate world of Mingering Mike, a soul superstar of the 1960s and 1970s who released an astonishing fifty albums and at least as many singles in just ten years. But Hadar had never heard of him, and he realized why on closer inspection: every album in the crate, as well as the records themselves, were made of cardboard. Each package was intricately crafted, complete with gatefold interiors, extensive liner notes, and grooves drawn onto the “vinyl.” Some albums were even covered in shrinkwrap, as if purchased at real record stores.

Hadar put his detective skills to work and soon found himself at the door of Mingering Mike. Their friendship blossomed and Mike revealed the story of his life and the mythology of his many albums, hit singles and movie soundtracks.

A solitary boy raised by his brothers, sisters and cousins, Mike lost himself in a world of his own imaginary superstardom, basing songs and albums on his and his family’s experiences. Early teenage songs obsessed with love and heartache soon gave way to social themes surrounding the turbulent era of civil rights protests and political upheaval – brought even closer to home when Mike himself went underground, dodging the government for ten years after going AWOL from basic training.

In “Mingering Mike’s Supersonic Greatest Hits,” on view through Aug. 2, Hadar recounts the heartfelt story of Mike’s life and collects the best of his albums and 45s.

Mingering Mike, like folk artists, uses biblical and cultural imagery as subjects for his work. But Mike operated on an even deeper level of imaginative force, finding his inspiration in his own lyrics, his own song titles, his own obsessions. Mike shares another fundamental principal with other folk artists among this visual tradition: he is often teaching or commenting on moral and spiritual issues. In a way, public instruction is not so different from what Mingering Mike is doing, in his own miniaturized and eccentric domain. It is this impulse to communicate what he has learned, and what he feels about the power of visual art to express, that links him not only to other black visionary artists of his own and earlier generations, but to the very mainstream of American art.

For more information visit www.AmericanArt.si.edu