The hobos feared the tramps and the tramps viewed the hobos as suckers for work. Hobos, wandering migrant workers, stopped in a place long enough to do a job and then moved on. Although tramps were traveling men, too, they rarely lifted a finger unless coerced. Yet, in the late 1800s, itinerants of both persuasions jumped the same trains, were locked up in the same jail cells and ate and slept in the same hobo “jungles.”

As they warmed themselves around the campfires and shared stories of their daily survival, the hobos whittled and the tramps carved intricate, and sometimes whimsical, objects that have come to be known as Tramp Art.

From the 1870s to the 1930s, this relatively little-known folk art blossomed. Although it may have originated with displaced individuals, many a farmer, factory worker and laborer turned out his own version of chip-carved and layered pieces in his own home-based workshops.

Actually, the name Tramp Art was applied to this art form in the 1950s. There were more than 40 ethnic groups creating this art in this country. There is even evidence of retired Civil War soldiers making tramp art in their later years.

Also known as chip art, tramp art shares its vocabulary with quilts, since both traditions use salvaged materials cut into geometric shapes and layered together to create utilitarian objects. Using recycled wood, primarily from the then-ubiquitous cigar boxes or produce crates, and with simple pocketknives as their primary tool, these unschooled artisans carved the discarded wood pieces into objects of every conceivable shape.

The art form was driven by the abundance of wooden cigar boxes and their availability to the artists. The wooden boxes were used for cigar sales in the 1850s, and – since revenue laws did not permit the boxes to be used a second time for cigars – enterprising souls found new uses for the boxes. Since the boxes were plentiful, free and easily carved, ornamenting them by chip carving became popular.

The technique consisted of notch-carving each piece of cigar-box wood with consecutive Vs around its edges. Then it was layered with another piece that had been notched similarly, each layer a bit smaller than the preceding one. The artist then had to assemble the individual pieces of carved wood into a recognizable object. Layer upon layer of decorated wood would become a decorative and, typically, functional item.

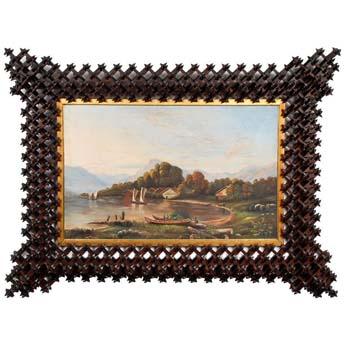

Another tramp art technique, called the “crown of thorns,” involved the interlocking of small, notched pieces of wood, much like a log cabin is built. The interlocking pieces were layered and formed a star effect.

Tramp art was an “everyman” craft, practiced by humble men who made objects for their own use or, sometimes, for barter: a picture frame for a daughter’s wedding; a jewelry box, festooned with hearts, for a beloved wife; a gift for a friend. These pieces spoke of devotion and love and the need for these workers to make things of beauty. The heart motif is a common one, as were stars and crucifixes.

Many dealers of folk art and antiques sell the myriad forms of tramp art, including boxes, picture frames, religious artifacts and even larger pieces of furniture. Some pieces were painted, and, these days, anything with the rich patina of old paint is sought-after. Many pieces were clear-coated to show the wood grain.

Prices for tramp art have increased significantly within the last decade, especially since American folk art has gained a huge following with collectors and decorators. Folk art – and tramp art, specifically – seems to attract many younger collectors, perhaps due to its whimsical nature.

The value of a piece reflects the intricacy of the object, the uniqueness of the form and the condition, but, generally, good quality examples can range from a couple hundred dollars for a box up to several thousand for an altar or a cabinet. The beauty of collecting this vintage art of hardscrabble origins is in appreciating how such humble materials have yielded such a tremendous breadth of very distinctive work.

Michelle Galler has been an antiques dealer for more than 25 years. Her shop is in Rare Finds, 211 Main Street, Washington, Virginia. She also consults from her 19th century-home in Washington. Reach her at antiques.and.whimsies@gmail.com.

- Yelp