Shirin Neshat at the Hirshhorn

By • July 16, 2015 0 986

There is a moment in artist Shirin Neshat’s short film, “Munis,” where a dead man is lying on the ground of an empty stone courtyard beside a dead woman. “In place of past and remembrance,” says the dead man, speaking in Persian, “all that remains are my dreams.” The scene is a sort of magical encounter between the recently deceased, and the statement is not so much a symbol for anything as a blunt expression of sociological displacement.

The short film follows Munis, a young Iranian woman in Tehran in the summer of 1953, as she listens to radio reports of clashes between supporters of the Mosaddeq government and unnamed “opposition groups” aided by “foreign forces.” As the radio conveys Mosaddeq’s exhortation to the Iranian people to “stand firm,” Munis’s brother enters, chastising her to get ready to meet a potential suitor. She ignores him, but he yanks the cord from the radio, severing her only link to the outside world.

Stepping outside to the rooftop of their home, she listens to protestors chanting in the distance. Munis then looks down to see an injured demonstrator collapse on the street below. She stares at him for a long moment, and then leans forward and falls silently to her death — or rather, she drifts weightlessly as a feather to the ground.

Lying beside the dead man on the ground, Munis’s conversation with the dead man commences. She comes into his dream, and we find her suddenly amid a throng of proShah demonstrators, at first observing and then shaking her fists and yelling slogans of resistance as the crowd is ruthlessly dispersed by the military. Only in death can she finally participate in the strange carnival of political unrest.

It is impossible to disentangle Shirin Neshat’s work and biography from the turbulent recent history of Iran, the country where she was born in 1957 and lived until 1975. As she herself observes, “Every Iranian artist is, in one way or another, political. Politics has defined our lives.”

“Shirin Neshat: Facing History,” now on view (through Sept. 20) at the Hirshhorn Museum, seeks to illuminate the political and cultural influences that have informed Neshat’s creative life. The first Hirshhorn exhibition organized under the directorship of Melissa Chiu, the show confronts the complex cultural dynamics of our day with work that offers a transnational perspective, an invaluable perspective for understanding the contemporary art world.

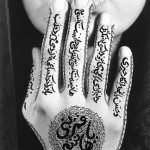

Presenting Neshat’s work in a sequence that allows viewers to experience an unfolding of history through the artist’s eyes, the exhibition opens with “Munis” (2008), set in 1953 during the coup that ousted Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddeq from power and consolidated the rule of Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi. It then moves to the photographic and video works Neshat made in response to her first visits to Iran since the establishment of the Islamic Republic in 1979. Finally it progresses to her monumental photographic series, “The Book of Kings” and “Our House Is On Fire,” created in the wake of the Iranian Green Movement protests of 2009 and the subsequent Arab Spring uprisings across the Middle East.

Consistent in all of these works is Neshat’s depiction of women as a sometimes hidden, but potent, source of resistance and strength. Often in contrast to their male counterparts, Neshat’s female characters are rebellious, always taking action.

In Neshat’s short film “Turbulent,” a man sings a charming waltz of an Iranian song to a group of men, who cheer merrily. As soon as he concludes, a woman, projected onto a screen on the opposite wall, emits a sound then slowly accelerates into a startling, unpredictable, gut-wrenching surge of musical expression, part song, part force of nature. It is not a mere performance such as the man delivered — it is something simmering from deep within that comes roiling to the surface. The men watch her from the opposite screen, stunned, speechless and unmoving.

The raw power and emotional energy of this video will likely floor you. And that would be enough. But it is worth knowing, going in, that in Iran, women are forbidden from singing in public.

So while this exhibition might at first seem oppressively political in its message, and out of place in an art museum, Neshat’s works are deeply human meditations on freedom and loss, at once personal, political and allegorical.

“Munis,” for instance, is part of a larger project that Neshat pursued between 2003 and 2009 to create a series of video installations — and even a feature film — based on the 1989 magic realist novella by Shahrnush Parsipur, “Women Without Men,” which tells the stories of five women whose troubled lives converge in a mysterious orchard.

Despite the complex and dynamic historical and political implications, there is such raw, aesthetic beauty to everything in the exhibition that you can allow yourself to deal with the art on its own terms. Neshat’s vision and delivery is so clear and powerful, it feels natural to let the art unfold simply before you.

This is work that is searching for liberation in expression and finding it in strange places, beyond the judgement of politics and the politics of judgement. It is found within, underneath the government-sanctioned hijabs that women are required to wear around their heads, beyond the strict Iranian constitution that controls both the public and private lives of women in the society.

Neshat finds freedom in the internal expression, and writes it large for those who don’t have the privilege to release it.

- “Ghada,” from “Our House Is on Fire” series, 2013. | Photo courtesy of Gladstone Gallery.