U.S. Gives Actress Ingrid Bergman Stamp of Approval

By • September 22, 2015 0 1823

For the true movie stars, the accolades never quite end.

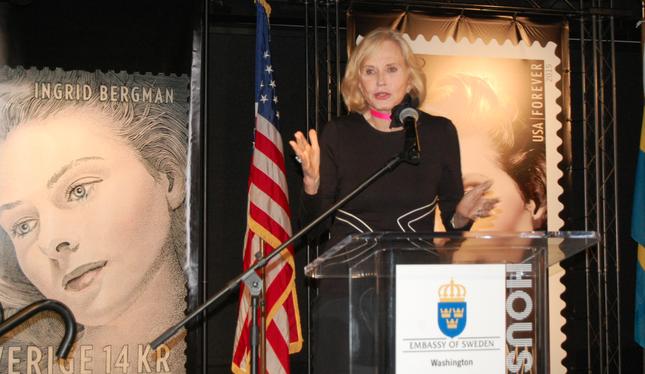

That was surely the case for the incandescent Ingrid Bergman, who was, as the veteran Washington movie critic Arch Campbell noted, “one of the great female stars of all time,” and who was honored yet again with a stamp ceremony at the House of Sweden in Georgetown on Sept. 9.

The U.S. Postal Service, in conjunction with their Swedish counterparts Posten AB, commemorated Bergman in a special ceremony at House of Sweden, with a Hollywood Forever Stamp which features the luminous actress in a classic photograph by Laszlo Willinger from the 1940s, when Bergman achieved celebrity, fame and her first Oscar.

The ceremony included the unveiling of two Swedish stamps. Mostly, it was an occasion of celebration, which included a Hollywood-style dance party where glam-sparkling young attendees joined the party to the music of the Cotton Club, which swayed between contemporary and disco sounds, while couples, many of them who had not been born when Bergman passed away in 1982, danced the night away.

Mostly, it was Ingrid Bergman everywhere you looked—posters from her famous Hollywood movies like “Notorious,” “Gaslight,” and of course “Casablanca” filled the walls, along with posters for lesser known films from her early, youthful career in Sweden.

Guests could also get an idea of the size of Bergman’s career—and her long-lasting impact—from exhibits put together by the Swedish Film Institute. There were also clips from her films, including a tender scene from “For Whom the Bell Tolls,” the 1940s adaptation of Ernest Hemingway’s novel about the Spanish Civil War, which starred a stoic, brave Gary Cooper and Bergman as the stunning Maria, complete with short blonde hair and eyes so blue they defined the color.

Bergman had a remarkable career, given that she was a young girl from Sweden, who had built a strong career there and came to Hollywood in 1939, after being discovered by David O. Selznick (“Gone With the Wind). She was brought to Hollywood to star in “Intermezo,” a redo of the Swedish original, which had Leslie Howard as her co-star. Selznick, according to his son, had some doubts—she couldn’t speak English, she was tall, she sounded too German and her beauty was unconventional but affecting.

She starred in a number of films small roles in “Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde,” and “Gaslight,” for which she won an Oscar, as well as “Joan of Arc,” “Notorious”, “Saratoga Trunk” and “Casablanca,” a film that defied its period setting and became a classic, re-discovered by future generations.

Pia Lindstrom, a noted television news professional in New York and San Francisco, in an interview after the ceremonies, said that her mother “was the perfect screen actress. All the acting was in the face, the eyes, she was the personification of screen acting—her face contained all the emotions, she could be charming, flirtatious, serious, passionate. She acted for the camera, not the other actors. That was her audience, the light would hit her eyes, and she lit up the screen.

“I think my mother was most happy, when she was in front of a camera,” Lindstrom said. “I mean, here was a girl who had lost her mother early on, and her father in her teens, and acting was a way to retreat into make believe. And she had a tremendous gift for it.”

Everyone remembers “Casablanca,” where she was Bogart’s girl, the city was full of refugees, Nazis, suave Frenchman, forgers and thieves, and Bogart said “just play it, Sam” and “Here’s looking at you, kid” and she said, “We’ll always have Paris” and we still do.

She led a big and often turbulent life—leaving her husband and family to take up with the Italian director Roberto Rossellini while filming “Stromboli.” The affair caused a scandal in the United States—apparently she was condemned from the Senate floor. She married Rossellini, and divorced him after three children (one of them was Isabella Rossellini), and eventually returned to a forgiving Hollywood. She triumphed again with “Anastasia” and “Murder on the Orient Express,” winning an Oscar each for best actress and best supporting actress. She ended her career in triumph—directed by Ingmar Bergman in “Autumn Sonata” and portraying Golda Meir while battling cancer.

“I think she was forward looking in the sense that she did what she wanted,” Lindstrom said. “She was very strong willed. I don’t know if you call that feminism. I think it was her. After all, she spent most of her life being married, and she spent most of it working.”

She could haunt you for a long time, if you encountered her on film. She dominated her pet project “Joan of Arc”— a not particularly good film—with her portrait of Joan in which she triumphed and suffered passionately, combining a stunning spirituality with a hint of carnality. Not everyone can bring that off.

Now, she has her own stamp, as if she needed another way to remember. But the image seem classic, and when you see one, it wouldn’t be unreasonable to whisper “Here’s looking at you, kid.”

- Pia Lindstrom, daughter of Ingrid Berman, at House of Sweden and U.S. Postal Service ceremony Sept. 9. | Robert Devaney