17 Series at the National Gallery

By • October 26, 2015 0 1045

It is typically single works of art that survive in the public consciousness, becoming the iconic masterpieces by which we gauge our cultural evolution. Picasso’s “Guernica” gives us the resonant anguish of World War II, while Pollock’s “Autumn Rhythm” seems to express the frenzied, explosive momentum of postwar America.

Necessary landmarks in our sociological timelines, pieces like these take on momentum as they sink more indelibly into our cultural identity. They become chapter markings in art history and bulwarks of generational progression, almost to the point where — unburdened by outsized symbolic density or perversely cheapened by sheer popularity — they are impossible to admire as works of art.

I have seen T-shirts with Warhol’s portrait of Che Guevara. I have seen the immaculate groin of Michelangelo’s “David” screenprinted on men’s underpants. I have seen Munch’s “The Scream” sold as an inflatable doll. I have seen “Mona Lisa” Halloween costumes, complete with handlebar-mounted picture frames.

These things cannot be unseen, and (as ludicrous of a complaint as this is) the experience of these artworks is inevitably, inalterably affected. If I want to truly, earnestly look at a painting by Van Gogh, for instance — to lose myself in its raw artistry and lap up its formal beauty — it almost has to be one I’ve never seen before. Otherwise, I find myself standing in front of a historical artwork “document” and thinking nothing more than, “How important!”

These days, I find myself most intrigued, fulfilled and overjoyed as a viewer by smaller works and multi-part series, which artists have been undertaking for centuries. It is here that artists can deal with subjects on a scale not possible in larger single works, exploring process, materials, color and theme — the meat of it all — that make up their daily practice and inform their larger works.

This type of artistic production was especially prevalent in the 1960s, as artists dedicated to conceptual, minimalist and pop approaches explored the potential of serial procedures and structures, as well as the rapidly expanding influence and implications of 20th-century mass media.

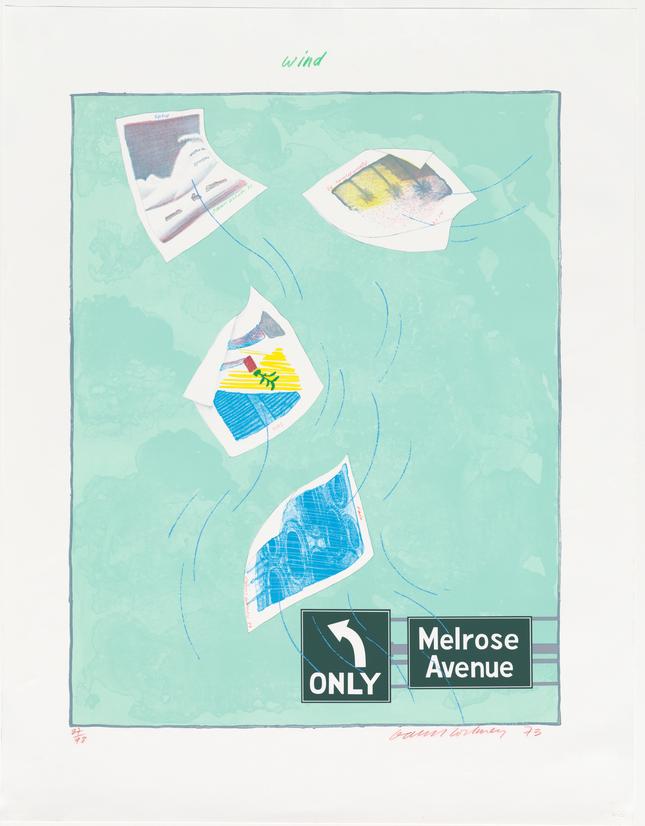

In the 1960s, Los Angeles became home to a printmaking boom. Founded in 1966, Gemini G.E.L. (Graphic Editions Limited), a fine-art workshop on Melrose Avenue, started collaborating with prominent artists, creating innovative prints that helped launch a renaissance of the graphic arts.

Coinciding with Gemini’s 50th anniversary, “The Serial Impulse at Gemini G.E.L.,” on view through Feb. 7 at the National Gallery of Art, sheds light on this phenomenon.

Some of the most important and influential artists of the past five decades have conceived and produced groundbreaking series — both print and sculptural — at Gemini. The exhibition showcases, in their entirety, 17 innovative series created at the workshop over the past five decades, including seminal early works by artists such as Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Rauschenberg and Frank Stella, as well as more recent serial projects by John Baldessari, Julie Mehretu and Richard Serra.

At Gemini G.E.L., artists are encouraged to do “projects in depth,” says Sidney B. Felsen, co-founder and co-director.?As living proof, this exhibition reveals the wide range of artistic approaches to serial production from all decades of Gemini’s history. What is perhaps most exciting about these series is seeing firsthand how the sequence is essential to the way the group is understood — quite a different way of looking at art than the classical pattern of standing in front of a single painting, then clearing it from your mind to observe the next one.

Another interesting aspect of the exhibition is that it lacks a traditional entrance and exit. As a way of “exploring the potential impact of alternate sequences,” it is structured so that it may be entered at either end of the gallery.?This is a chance to see work from familiar artists with fresh eyes, to delve into the machinations of their process.?It has been a long time since I could look at anything by Roy Lichtenstein or Jasper Johns without being unconsciously distracted or prematurely exhausted by the postmodern implications that cling to their very legacy. With this exhibition, I was free, and I felt like the artists were too.