In many important ways, “Appomattox,” the dramatically revised work by composer Philip Glass and librettist Christopher Hampton, is the most original and in-the-times-and-moment opera ever staged by Washington National Opera.

Even with the news in the world and the United States overwhelmed by the Paris terrorist attacks and their aftermath, “Appomattox” speaks to the times we live in, to the here and now. It challenges, and ultimately haunts, an audience in ways that traditional and more familiar operas rarely if ever do. In doing so, it becomes in the end a triumph of cooperative artistry — of words, dramatic narrative and music acting in concert, of acting and singing, of visual power that attempts to match that of painting and film.

The original “Appomattox,” also by Glass and Hampton, largely focused on the Civil War. It has been recast as Act One of the expanded opera. But this ambitious world-premiere production goes on to link the ending of the Civil War — with all of its promise and considerable hope for the freed slaves — to the Selma days of the 1960s, specifically, the negotiations and battles over the Voting Rights Act.

Afterward, when audience members are alone with their thoughts, the entire enterprise seems to place itself squarely in our daily life, this American year of Ferguson and Baltimore, of police shootings and the current outcries and demonstrations in response to the continued presence of racism in our society, in our cities and on our campuses.

That call for a national debate about race may for a time, or longer than that, be drowned out by the shock and threat now posed by terrorism, whose face is the nihilistic and implacable force of ISIS. But the effect of a work like “Appomattox” lingers nonetheless on several levels, primarily because it such a purely American piece. And while it is operatic in its emotions, “Appomattox” avails itself of few operatic tropes.

You’ve probably never seen so many historical personages as you will in this opera, which runs over three hours: Abraham Lincoln, Frederick Douglass, Robert E. Lee, Ulysses and Julia Grant, Mary Todd Lincoln, LBJ, Martin Luther King, Jr., a young civil rights activist named John Lewis, a white civil rights activist from Detroit named Vi Liuzzo who was murdered by Klansmen, J. Edgar Hoover, George Wallace and a host of others — including Edgar Ray Killen, the horribly foul Klansman charged in the murders of three civil rights workers in Mississippi at age 80, years after the killings in 1964.

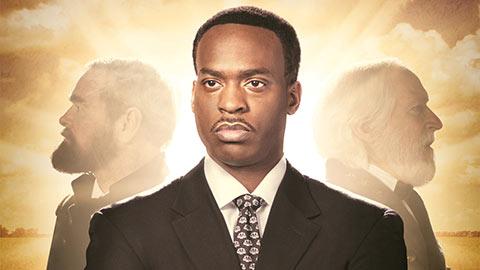

This is history writ large. Convincingly, like a nonfiction drama, it works almost cinematically. In fact, “Appomattox” functions more like a spoken drama in which the dialogue is sung, glorified (music-ified, if you will) and embellished in astonishingly beautiful choral works, notably the opening gathering of soldiers singing “Tenting on the Old Campground.” In the second act, the chorus erupts into a truly glorious “Battle Hymn of the Republic” (“Glory, glory, hallelujah!”), which bass Solomon Howard, as Martin Luther King, Jr., takes over in an aria of triumph.

Most of the parts are double cast. Howard, for instance, plays both King and Douglass and has pointed conversations with LBJ and Lincoln in both parts. I say conversations because the encounters, like many in the opera, come off genuinely conversational and natural. Glass’s difficult music also seems in partnership with the words. The music is respectful, the tone muted; it decorates more than emphasizes, with one singular exception, noted below.

Tom Fox takes over parts of the second act as LBJ. He is the profane — very profane — president in all his crass empathy. His singing in fact makes his brash, hardtack profanity even more effective.

The connection between time periods is made at the end of the first act when, after a massacre of black troops in Louisiana, a reporter for an African American newspaper despairs of the future in a searing turn by Frederick Ballentine. One hundred years later, the promise of the vote is about to be achieved.

This is an American opera, loud and emotionally on the money. It probably contains more raw language (including numerous expressions of the N-word) than anyone may have experienced in an opera. Most chilling is a conversation — unrepentant, hateful, smug, cruel — between Killen (played powerfully by David Pittsinger) and James Fowler (Keriann Otaño), a policeman charged in the death of civil rights activist Jimmie Lee Jackson. Here, Glass’s music takes a turn into unknown territory, becoming a kind of insane explosion of sounds, a counterpoint to the calm, bitter, racist conversation between the two men.

Artfully paced and directed by Tazewell Thompson, this beautifully acted and staged production paints — in its broad narrative strokes, striking characterizations and rich and jarring music — a vibrant, even burning, canvas that portrays the jagged course and imbedded wound of racism in America. It will sweep you up.

“Appomattox” runs through Nov. 22 at the Kennedy Center Opera House.