Muhammad Ali, 1942-2016

By • July 7, 2016 0 701

Muhammad Ali, born Cassius Clay in Kentucky, died of septic shock June 3 at a hospital in Scottsdale, Arizona, where he had been living. He was 74. The world seemed a little smaller in the aftermath of the news, which spread around the world over the weekend, accompanied by tributes, flowers of the verbal kind, a train of memories, the rat-a-tat of his verbal gifts, images of fights won and rarely lost.

He had battled Parkinson’s disease for decades. It had diminished his abilities, his voice, but not his fame, his impact, his greatness. In the end, the illness did not so much defeat him as release him from pain. In the end, death or a doctor or a guiding spirit said, “Fight’s over. You won.”

The greatness of the three-time heavyweight boxing champion of the world was certain. He, himself, said so, proclaiming often that he was, indeed, “The Greatest” — for sheer presence, dexterity, style, charisma, ring prowess, courage, charm and just a whole bunch of other things, including perhaps being one of the earliest and best rappers, on the biggest stage in the world.

When you stand alone in the ring, gloves high in the air over countless great rivals, you can surely get a whiff of what is to be the greatest, and can hold onto it as a claim and a keepsake.

He owned boxing most of the time he was in the sport. But who he was and how he was — that made all the difference in the world. He was brash, he was quick, he was eloquent and funny and sometimes mean. He was proud and pretty, which, when you say it to the world, is vanity justified, and brings on a smile. He came from no noted beginnings, no star in the sky saying things were going to happen, out of Louisville, a young, unbowed black man who rose to win Olympic boxing medals, to a career in the ring that brought him right to the top of the world.

He was Cassius Clay then, already cognizant of a better future. The boxing was memorable. In that heavyweight world, he was consistently outweighed, outbigged, but he was hardly ever outboxed, outsmarted or outhit. When he knocked out the menacing, lumbering Sonny Liston with what many people thought of as a phantom punch, he was on top, literally and in every sense of the word and words, of which there were many.

He had the courage of the boxer, the truly great ones, in the ring, but he displayed more of it outside. He converted to the Nation of Islam, and refused to enter the draft, a costly stand and stance, which for a time got him banned from boxing and lost him his crown until he reentered the lists.

In the 1960s, he was a controversial figure. Not everybody loved Muhammad Ali, the name he took and the man he became. This was the era of the loudest, most violent and broad civil rights struggles, when people clashed in the streets, the silent majority emerged loudly and the nation was torn apart by race, the war and various revolutions, including the cultural one.

Ali stood up, and if he got knocked down in the ring a few times in later years, he never got knocked down, let alone out, in the world.

The haters were out there. I remember when I worked on a daily newspaper in the 1960s, and Ali, who had already expressed his opposition to the war, was fighting one night. The sports editor wrote a column about the fight in which he wrote words to the effect that he had trouble with his television that night, that he could only get one color: yellow.

This was not in the South but in a town just outside of San Francisco.

He was an unstoppable force, and for African Americans he was a source of great pride. The brashness, the boldness, the bragging, the immodesty, the sheer musicality and funny stuff, the way he embraced children, all made people want to be like him.

Except, of course, that you couldn’t. No one was that funny, that smart, that ever-present. He was like a sun king or prince. He became Muhammad Ali because “Cassius Clay is a slave name. I didn’t choose it, and I didn’t want it. I am Muhammad Ali, a free name, it means beloved of god, and I insist people use it when they speak to me and of me.” And so we did and do now.

He predicted knockouts and rhymed the predictions. He was like some kind of modern Johnny Appleseed with his (so to speak) bragging writes. Before the Rumble in the Jungle against George Foreman, he said and he did: “I done wrestled with an alligator, I done tussled with a whale; handcuffed lighting, thrown thunder in jail; only last week, I murdered a rock, injured a stone, hospitalized a brick; I’m so mean I make medicine sick.”

When Parkinson’s grabbed him by the soul, you could see him trying to get it to let go. It never quite did, but he did get around it to his own nobility at times. That appearance at the Atlanta Olympics, one hand shaking, the other holding the torch, was unforgettable to the millions who saw it.

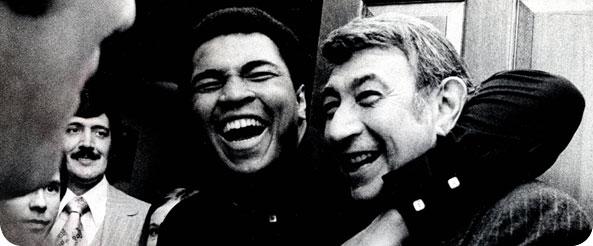

We saw him here, once. Chris Murray and his Govinda Gallery showed an exhibition of photographs by Ali’s longtime friend and gifted artist Howard Bingham. The images were of the life and some times of the Champ, and Ali himself showed up. There were television people and lines of folks stretched out onto Prospect Street. He sat and said little, but looked everyone who came up to him straight in the eye and signed the catalogue and embraced children. The president at the time — that would have been, in 1995, Bill Clinton — might as well have showed up. He would have stayed in line unnoticed.

We saw him too at a screening of “Ali,” the biopic starring a toned-up Will Smith, at the Uptown Theater. He was slower, but he still glowed in the light. He was in the audience and often people turned to look at him.

Every day, then and now, he was, as he said, “Free to be what I want.”

He deserved, and earned, every bit of that freedom.